Introduction

In two of my previous articles, I Know You Understand Hoisting, But Do You Really Understand It? and All Functions Are Closures: Discussing Scope and Closure in JS, I talked about the differences between the scopes of let and var.

The scope of let is block, while var is function. This is a classic example:

for(var i=1; i<=10; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i)

})

}It was originally expected to output 1 to 10 in order, but unexpectedly output 10 11s. The reason behind this is that the i on the third line always has only one, which is the var i declared in the for loop, and it is the same variable from beginning to end.

The classic solution is also very simple, just change var to let:

for(let i=1; i<=10; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i)

})

}The reason why this works is that the above code can be seen as the following form:

{

let i=1

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i)

})

}

{

let i=2

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i)

})

}

...

{

let i=10

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i)

})

}Since the scope of let is block, there is actually a new i in each round of the loop, so there are 10 different i after the loop runs 10 times, and of course, 10 different numbers are output in the end.

Therefore, the biggest difference between var and let in this example is the number of variables, the former has only one, while the latter has 10.

Okay, now that you know the difference between let and var, let’s take a look at the main issue of this article.

In fact, this issue comes from a question raised by @getify, the author of YDKJS (You Don’t Know JS), on his Twitter:

question for JS engines devs…

is there an optimization in place for this kind of code?for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) { // no closure }IOW, where the behavior of creating a new

iper iteration is not needed nor observable… does JS skip doing it?

If you didn’t understand it very well, you can continue to read the other tweet:

here’s a variation on the question… will JS engines exhibit much performance difference between these two loops?

for (var i = 0; i < 100000000; i++) {

// do some stuff, but not closure

}

for (let i = 0; i < 100000000; i++) {

// do the same stuff (no closure)

}Simply put, when we usually use let with loops, isn’t it like we said above, there will be a new i in each round? If so, then there should be a performance difference between var and let, because let must new a new variable in each round, so let will be slower.

If the loop does not need a new i in each round, will the JS engine optimize it? This issue is mainly to explore whether the JS engine will optimize this behavior.

So how do we know? Either you are a JS engine developer, or you can look at the JS bytecode, but both of these difficulties are a bit too high. But don’t worry, there is a third way: look at the JS bytecode.

JavaScript Bytecode

If you don’t know what bytecode is, you can refer to this classic article: Understanding V8’s Bytecode, Chinese version: Understanding V8’s Bytecode.

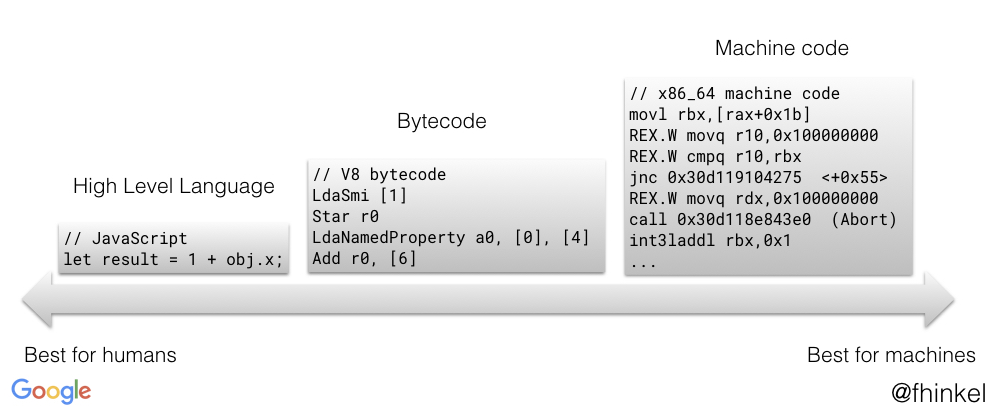

Let’s start with the clearest picture explained in the article:

When executing JavaScript, V8 first compiles the code into bytecode, then compiles the bytecode into machine code, and finally executes it.

Let’s take an example from real life. If you want to translate an English article into Classical Chinese, you usually translate the English article into vernacular Chinese first, and then translate it into Classical Chinese from vernacular Chinese. Because it is too difficult to translate directly from English to Classical Chinese, it is easier to translate it into vernacular Chinese first; at the same time, some optimizations can be made when translating into vernacular Chinese, which will make it easier to translate into Classical Chinese.

In this metaphor, plain text is the protagonist of our article: bytecode.

When writing C/C++, if you want to know whether the compiler will optimize a certain piece of code, the most direct way is to output the compiled assembly code. By reverse-engineering the assembly language, you can know whether the compiler has done anything.

Bytecode is the same. You can reverse-engineer the generated bytecode to see if V8 has done anything.

So how do you view the bytecode generated by V8? The easiest way is to use the Node.js command: node --print-bytecode a.js, just add the --print-bytecode flag.

But if you try it, you will find that a lot of things are output, which is normal. Because there are a lot of built-in things besides the code you wrote, we can use --print-bytecode-filter to filter the function names.

var and let: Round 1

The test code I prepared is as follows:

function find_me_let_for(){

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

console.log(i)

}

}

function find_me_var_for() {

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

console.log(i)

}

}

find_me_let_for()

find_me_var_for()Then you can use the command: node --print-bytecode --print-bytecode-filter="find_me*" a.js > byte_code.txt, and save the result to byte_code.txt. The content is as follows:

[generated bytecode for function: find_me_let_for]

Parameter count 1

Frame size 24

86 E> 0x77191b56622 @ 0 : a0 StackCheck

105 S> 0x77191b56623 @ 1 : 0b LdaZero

0x77191b56624 @ 2 : 26 fb Star r0

110 S> 0x77191b56626 @ 4 : 0c 0a LdaSmi [10]

110 E> 0x77191b56628 @ 6 : 66 fb 00 TestLessThan r0, [0]

0x77191b5662b @ 9 : 94 1c JumpIfFalse [28] (0x77191b56647 @ 37)

92 E> 0x77191b5662d @ 11 : a0 StackCheck

127 S> 0x77191b5662e @ 12 : 13 00 01 LdaGlobal [0], [1]

0x77191b56631 @ 15 : 26 f9 Star r2

135 E> 0x77191b56633 @ 17 : 28 f9 01 03 LdaNamedProperty r2, [1], [3]

0x77191b56637 @ 21 : 26 fa Star r1

135 E> 0x77191b56639 @ 23 : 57 fa f9 fb 05 CallProperty1 r1, r2, r0, [5]

117 S> 0x77191b5663e @ 28 : 25 fb Ldar r0

0x77191b56640 @ 30 : 4a 07 Inc [7]

0x77191b56642 @ 32 : 26 fb Star r0

0x77191b56644 @ 34 : 85 1e 00 JumpLoop [30], [0] (0x77191b56626 @ 4)

0x77191b56647 @ 37 : 0d LdaUndefined

146 S> 0x77191b56648 @ 38 : a4 Return

Constant pool (size = 2)

Handler Table (size = 0)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

[generated bytecode for function: find_me_var_for]

Parameter count 1

Frame size 24

173 E> 0x77191b60d0a @ 0 : a0 StackCheck

193 S> 0x77191b60d0b @ 1 : 0b LdaZero

0x77191b60d0c @ 2 : 26 fb Star r0

198 S> 0x77191b60d0e @ 4 : 0c 0a LdaSmi [10]

198 E> 0x77191b60d10 @ 6 : 66 fb 00 TestLessThan r0, [0]

0x77191b60d13 @ 9 : 94 1c JumpIfFalse [28] (0x77191b60d2f @ 37)

180 E> 0x77191b60d15 @ 11 : a0 StackCheck

215 S> 0x77191b60d16 @ 12 : 13 00 01 LdaGlobal [0], [1]

0x77191b60d19 @ 15 : 26 f9 Star r2

223 E> 0x77191b60d1b @ 17 : 28 f9 01 03 LdaNamedProperty r2, [1], [3]

0x77191b60d1f @ 21 : 26 fa Star r1

223 E> 0x77191b60d21 @ 23 : 57 fa f9 fb 05 CallProperty1 r1, r2, r0, [5]

205 S> 0x77191b60d26 @ 28 : 25 fb Ldar r0

0x77191b60d28 @ 30 : 4a 07 Inc [7]

0x77191b60d2a @ 32 : 26 fb Star r0

0x77191b60d2c @ 34 : 85 1e 00 JumpLoop [30], [0] (0x77191b60d0e @ 4)

0x77191b60d2f @ 37 : 0d LdaUndefined

234 S> 0x77191b60d30 @ 38 : a4 Return

Constant pool (size = 2)

Handler Table (size = 0)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

The first line indicates which function it is, which is convenient for us to identify: [generated bytecode for function: find_me_let_for], followed by the actual bytecode.

Before looking at the bytecode, it is very important to have a preparatory knowledge that there is a temporary register called the accumulator in the environment where the bytecode is executed. If there is the letter a in the instruction, it is the abbreviation of the accumulator (hereinafter referred to as acc).

For example, the second and third lines of the bytecode: LdaZero and Star r0, the former is: LoaD Accumulator Zero, which sets the acc register to 0, and the next line Star r0 is Store Accumulator to register r0, which is r0=acc, so r0 will become 0.

I translated the above find_me_let_for into plain text:

StackCheck // 檢查 stack

LdaZero // acc = 0

Star r0 // r0 = acc

LdaSmi [10] // acc = 10

TestLessThan r0, [0] // test if r0 < 10

JumpIfFalse [28] // if false, jump to line 17

StackCheck // 檢查 stack

LdaGlobal [0], [1] // acc = console

Star r2 // r2 = acc

LdaNamedProperty r2, [1], [3] // acc = r2.log

Star r1 // r1 = acc (也就是 console.log)

CallProperty1 r1, r2, r0, [5] // console.log(r0)

Ldar r0 // acc = r0

Inc [7] // acc++

Star r0 // r0 = acc

JumpLoop [30], [0] // 跳到 line 4

LdaUndefined // acc = undefined

Return // return accIf you are not used to this form, it may be because you have not seen assembly language (in fact, assembly language is much more difficult than this…), and you will get used to it after reading it a few more times.

Anyway, the above code is a loop that will log r0 continuously until r0>=10. This r0 is the i in our code.

If you look closely, you will find that the bytecode generated by let and var versions is exactly the same, and there is only one variable r0 from beginning to end. Therefore, it can be inferred that V8 does optimize this situation and does not really create a new i for each loop. When using let, there is no need to worry about performance differences with var.

var and let: Round 2

Next, we can try the case where “a new i must be created for each loop”, that is, when there is a closure inside that needs to access i. The sample code prepared here is as follows:

function find_me_let_timeout() {

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

setTimeout(function find_me_let_timeout_inner() {

console.log(i)

})

}

}

function find_me_var_timeout() {

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

setTimeout(function find_me_var_timeout_inner() {

console.log(i)

})

}

}

find_me_let_timeout()

find_me_var_timeout()Using the same command as before, you can see the generated bytecode. Let’s first see if there is any difference between the two inner functions:

[generated bytecode for function: find_me_let_timeout_inner]

Parameter count 1

Frame size 24

177 E> 0x25d2f37dbb2a @ 0 : a0 StackCheck

188 S> 0x25d2f37dbb2b @ 1 : 13 00 00 LdaGlobal [0], [0]

0x25d2f37dbb2e @ 4 : 26 fa Star r1

196 E> 0x25d2f37dbb30 @ 6 : 28 fa 01 02 LdaNamedProperty r1, [1], [2]

0x25d2f37dbb34 @ 10 : 26 fb Star r0

0x25d2f37dbb36 @ 12 : 1a 04 LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

200 E> 0x25d2f37dbb38 @ 14 : a5 02 ThrowReferenceErrorIfHole [2]

0x25d2f37dbb3a @ 16 : 26 f9 Star r2

196 E> 0x25d2f37dbb3c @ 18 : 57 fb fa f9 04 CallProperty1 r0, r1, r2, [4]

0x25d2f37dbb41 @ 23 : 0d LdaUndefined

207 S> 0x25d2f37dbb42 @ 24 : a4 Return

Constant pool (size = 3)

Handler Table (size = 0)

[generated bytecode for function: find_me_var_timeout_inner]

Parameter count 1

Frame size 24

332 E> 0x25d2f37e6cf2 @ 0 : a0 StackCheck

343 S> 0x25d2f37e6cf3 @ 1 : 13 00 00 LdaGlobal [0], [0]

0x25d2f37e6cf6 @ 4 : 26 fa Star r1

351 E> 0x25d2f37e6cf8 @ 6 : 28 fa 01 02 LdaNamedProperty r1, [1], [2]

0x25d2f37e6cfc @ 10 : 26 fb Star r0

0x25d2f37e6cfe @ 12 : 1a 04 LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x25d2f37e6d00 @ 14 : 26 f9 Star r2

351 E> 0x25d2f37e6d02 @ 16 : 57 fb fa f9 04 CallProperty1 r0, r1, r2, [4]

0x25d2f37e6d07 @ 21 : 0d LdaUndefined

362 S> 0x25d2f37e6d08 @ 22 : a4 Return

Constant pool (size = 2)

Handler Table (size = 0)You can see that the only difference is that the let version has an additional ThrowReferenceErrorIfHole, which has been mentioned in I know you understand hoisting, but how deep do you understand?. It is actually the implementation of TDZ (Temporal Dead Zone) on V8.

Finally, let’s look at the main course, starting with var:

[generated bytecode for function: find_me_var_timeout]

Parameter count 1

Frame size 24

0x25d2f37d8d22 @ 0 : 7f 00 01 CreateFunctionContext [0], [1]

0x25d2f37d8d25 @ 3 : 16 fb PushContext r0

245 E> 0x25d2f37d8d27 @ 5 : a0 StackCheck

265 S> 0x25d2f37d8d28 @ 6 : 0b LdaZero

265 E> 0x25d2f37d8d29 @ 7 : 1d 04 StaCurrentContextSlot [4]

270 S> 0x25d2f37d8d2b @ 9 : 1a 04 LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x25d2f37d8d2d @ 11 : 26 fa Star r1

0x25d2f37d8d2f @ 13 : 0c 0a LdaSmi [10]

270 E> 0x25d2f37d8d31 @ 15 : 66 fa 00 TestLessThan r1, [0]

0x25d2f37d8d34 @ 18 : 94 1b JumpIfFalse [27] (0x25d2f37d8d4f @ 45)

252 E> 0x25d2f37d8d36 @ 20 : a0 StackCheck

287 S> 0x25d2f37d8d37 @ 21 : 13 01 01 LdaGlobal [1], [1]

0x25d2f37d8d3a @ 24 : 26 fa Star r1

0x25d2f37d8d3c @ 26 : 7c 02 03 02 CreateClosure [2], [3], #2

0x25d2f37d8d40 @ 30 : 26 f9 Star r2

287 E> 0x25d2f37d8d42 @ 32 : 5b fa f9 04 CallUndefinedReceiver1 r1, r2, [4]

277 S> 0x25d2f37d8d46 @ 36 : 1a 04 LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x25d2f37d8d48 @ 38 : 4a 06 Inc [6]

277 E> 0x25d2f37d8d4a @ 40 : 1d 04 StaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x25d2f37d8d4c @ 42 : 85 21 00 JumpLoop [33], [0] (0x25d2f37d8d2b @ 9)

0x25d2f37d8d4f @ 45 : 0d LdaUndefined

369 S> 0x25d2f37d8d50 @ 46 : a4 Return

Constant pool (size = 3)

Handler Table (size = 0)At the beginning, CreateFunctionContext creates a function context, and then you can see that the way of accessing variables is different from simply using temporary registers. Here, StaCurrentContextSlot and LdaCurrentContextSlot are used. If you encounter instructions that you don’t understand, you can check the definition in /src/interpreter/interpreter-generator.cc.

// StaCurrentContextSlot <slot_index>

//

// Stores the object in the accumulator into |slot_index| of the current

// context.

IGNITION_HANDLER(StaCurrentContextSlot, InterpreterAssembler) {

Node* value = GetAccumulator();

Node* slot_index = BytecodeOperandIdx(0);

Node* slot_context = GetContext();

StoreContextElement(slot_context, slot_index, value);

Dispatch();

}

// LdaCurrentContextSlot <slot_index>

//

// Load the object in |slot_index| of the current context into the accumulator.

IGNITION_HANDLER(LdaCurrentContextSlot, InterpreterAssembler) {

Node* slot_index = BytecodeOperandIdx(0);

Node* slot_context = GetContext();

Node* result = LoadContextElement(slot_context, slot_index);

SetAccumulator(result);

Dispatch();

}In short, StaCurrentContextSlot stores the contents of acc in a certain slot_index of the current context, while LdaCurrentContextSlot does the opposite, taking the contents out and putting them in acc.

So let’s take a look at the first few lines:

LdaZero

StaCurrentContextSlot [4]

LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

Star r1

LdaSmi [10]

TestLessThan r1, [0]

JumpIfFalse [27] (0x25d2f37d8d4f @ 45)This puts 0 into slot_index 4 of the current context, then puts it into r1, and then compares it to 10. This part is actually the i<10 in the for loop.

The second half:

LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

Inc [6]

StaCurrentContextSlot [4]Is actually i++.

So i will exist in the slot_index 4 of the current context. Now let’s take a look at the inner function mentioned earlier:

[generated bytecode for function: find_me_var_timeout_inner]

Parameter count 1

Frame size 24

332 E> 0x25d2f37e6cf2 @ 0 : a0 StackCheck

343 S> 0x25d2f37e6cf3 @ 1 : 13 00 00 LdaGlobal [0], [0]

0x25d2f37e6cf6 @ 4 : 26 fa Star r1

351 E> 0x25d2f37e6cf8 @ 6 : 28 fa 01 02 LdaNamedProperty r1, [1], [2]

0x25d2f37e6cfc @ 10 : 26 fb Star r0

0x25d2f37e6cfe @ 12 : 1a 04 LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x25d2f37e6d00 @ 14 : 26 f9 Star r2

351 E> 0x25d2f37e6d02 @ 16 : 57 fb fa f9 04 CallProperty1 r0, r1, r2, [4]

0x25d2f37e6d07 @ 21 : 0d LdaUndefined

362 S> 0x25d2f37e6d08 @ 22 : a4 Return

Constant pool (size = 2)

Handler Table (size = 0)Did you notice the line LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]? This line corresponds to what we said earlier, using this line in the inner function to take out i.

So in the var example, a function context is first created, and from start to finish, there is only one context, which puts i in the slot_index 4, and the inner function also takes i from this position.

Therefore, i only exists from start to finish.

Finally, let’s take a look at the more complex let version:

[generated bytecode for function: find_me_let_timeout]

Parameter count 1

Register count 7

Frame size 56

179 E> 0x2725c3d70daa @ 0 : a5 StackCheck

199 S> 0x2725c3d70dab @ 1 : 0b LdaZero

0x2725c3d70dac @ 2 : 26 f8 Star r3

0x2725c3d70dae @ 4 : 26 fb Star r0

0x2725c3d70db0 @ 6 : 0c 01 LdaSmi [1]

0x2725c3d70db2 @ 8 : 26 fa Star r1

293 E> 0x2725c3d70db4 @ 10 : a5 StackCheck

0x2725c3d70db5 @ 11 : 82 00 CreateBlockContext [0]

0x2725c3d70db7 @ 13 : 16 f7 PushContext r4

0x2725c3d70db9 @ 15 : 0f LdaTheHole

0x2725c3d70dba @ 16 : 1d 04 StaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x2725c3d70dbc @ 18 : 25 fb Ldar r0

0x2725c3d70dbe @ 20 : 1d 04 StaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x2725c3d70dc0 @ 22 : 0c 01 LdaSmi [1]

0x2725c3d70dc2 @ 24 : 67 fa 00 TestEqual r1, [0]

0x2725c3d70dc5 @ 27 : 99 07 JumpIfFalse [7] (0x2725c3d70dcc @ 34)

0x2725c3d70dc7 @ 29 : 0b LdaZero

0x2725c3d70dc8 @ 30 : 26 fa Star r1

0x2725c3d70dca @ 32 : 8b 08 Jump [8] (0x2725c3d70dd2 @ 40)

211 S> 0x2725c3d70dcc @ 34 : 1a 04 LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x2725c3d70dce @ 36 : 4c 01 Inc [1]

211 E> 0x2725c3d70dd0 @ 38 : 1d 04 StaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x2725c3d70dd2 @ 40 : 0c 01 LdaSmi [1]

0x2725c3d70dd4 @ 42 : 26 f9 Star r2

204 S> 0x2725c3d70dd6 @ 44 : 1a 04 LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x2725c3d70dd8 @ 46 : 26 f6 Star r5

0x2725c3d70dda @ 48 : 0c 0a LdaSmi [10]

204 E> 0x2725c3d70ddc @ 50 : 69 f6 02 TestLessThan r5, [2]

0x2725c3d70ddf @ 53 : 99 04 JumpIfFalse [4] (0x2725c3d70de3 @ 57)

0x2725c3d70de1 @ 55 : 8b 06 Jump [6] (0x2725c3d70de7 @ 61)

0x2725c3d70de3 @ 57 : 17 f7 PopContext r4

0x2725c3d70de5 @ 59 : 8b 33 Jump [51] (0x2725c3d70e18 @ 110)

0x2725c3d70de7 @ 61 : 0c 01 LdaSmi [1]

0x2725c3d70de9 @ 63 : 67 f9 03 TestEqual r2, [3]

0x2725c3d70dec @ 66 : 99 1c JumpIfFalse [28] (0x2725c3d70e08 @ 94)

186 E> 0x2725c3d70dee @ 68 : a5 StackCheck

221 S> 0x2725c3d70def @ 69 : 13 01 04 LdaGlobal [1], [4]

0x2725c3d70df2 @ 72 : 26 f6 Star r5

0x2725c3d70df4 @ 74 : 81 02 06 02 CreateClosure [2], [6], #2

0x2725c3d70df8 @ 78 : 26 f5 Star r6

221 E> 0x2725c3d70dfa @ 80 : 5d f6 f5 07 CallUndefinedReceiver1 r5, r6, [7]

0x2725c3d70dfe @ 84 : 0b LdaZero

0x2725c3d70dff @ 85 : 26 f9 Star r2

0x2725c3d70e01 @ 87 : 1a 04 LdaCurrentContextSlot [4]

0x2725c3d70e03 @ 89 : 26 fb Star r0

0x2725c3d70e05 @ 91 : 8a 1e 01 JumpLoop [30], [1] (0x2725c3d70de7 @ 61)

0x2725c3d70e08 @ 94 : 0c 01 LdaSmi [1]

293 E> 0x2725c3d70e0a @ 96 : 67 f9 09 TestEqual r2, [9]

0x2725c3d70e0d @ 99 : 99 06 JumpIfFalse [6] (0x2725c3d70e13 @ 105)

0x2725c3d70e0f @ 101 : 17 f7 PopContext r4

0x2725c3d70e11 @ 103 : 8b 07 Jump [7] (0x2725c3d70e18 @ 110)

0x2725c3d70e13 @ 105 : 17 f7 PopContext r4

0x2725c3d70e15 @ 107 : 8a 61 00 JumpLoop [97], [0] (0x2725c3d70db4 @ 10)

0x2725c3d70e18 @ 110 : 0d LdaUndefined

295 S> 0x2725c3d70e19 @ 111 : a9 Return

Constant pool (size = 3)

Handler Table (size = 0)Because this code is a bit too long and not easy to read, I modified it and rewrote a more straightforward version:

r1 = 1

r0 = 0

loop:

r4.push(new BlockContext())

CurrentContextSlot = r0

if (r1 === 1) {

r1 = 0

} else {

CurrentContextSlot++

}

r2 = 1

r5 = CurrentContextSlot

if (!(r5 < 10)) { // end loop

PopContext r4

goto done

}

loop2:

if (r2 === 1) {

setTimeout()

r2 = 0

r0 = CurrentContextSlot

goto loop2

}

if (r2 === 1) {

PopContext r4

goto done

}

PopContext r4

goto loop

done:

return undefinedThe first key point is that CreateBlockContext is called for each loop, creating a new context, and then before the loop ends, the value of CurrentContextSlot (i.e., i) is stored in r0, and then in the next loop, the value of the new block context slot is read from r0 and incremented to implement the accumulation of different context values.

Then you might wonder, where exactly will this block context be used?

In the bytecode above, this part calls setTimeout:

LdaGlobal [1], [4]

Star r5 // r5 = setTimeout

CreateClosure [2], [6], #2

Star r6 // r6 = new function(...)

CallUndefinedReceiver1 r5, r6, [7] // setTimeout(r6)When we call CreateClosure and pass this closure to setTimeout, we also pass it in (only the context part is retained):

// CreateClosure <index> <slot> <tenured>

//

// Creates a new closure for SharedFunctionInfo at position |index| in the

// constant pool and with the PretenureFlag <tenured>.

IGNITION_HANDLER(CreateClosure, InterpreterAssembler) {

Node* context = GetContext();

Node* result =

CallRuntime(Runtime::kNewClosure, context, shared, feedback_cell);

SetAccumulator(result);

Dispatch();

}Therefore, when LdaCurrentContextSlot is called in the inner function, it will load the correct context and i.

Conclusion:

- The

varversion isCreateFunctionContext, and there is only one context from start to finish. - The

letversion callsCreateBlockContextfor each loop, and there are a total of 10 contexts. - In cases where closure is not needed, there is no difference between

letandvarin V8.

Summary

Some questions that you think have “obvious” answers may not necessarily be so.

For example, consider the following example:

function v1() {

var a = 1

for(var i=1;i<10; i++){

var a = 1

}

}

function v2() {

var a = 1

for(var i=1; i<10; i++) {

a = 1

}

}Which is faster, v1 or v2?

“v1 will re-declare and assign a every loop, while v2 will only declare it once outside and only assign it inside the loop, so v1 is faster.”

The answer is that they are exactly the same, because if you understand JS well enough, you will know that there is no such thing as “re-declaration”, as the declaration is processed during the compilation phase.

Even if there is a performance difference, how much is it? Is it worth our effort to focus on the difference?

For example, when writing React, we are often taught to avoid inline functions:

// Good

render() {

<div onClick={this.onClick} />

}

// Bad

render() {

<div onClick={() => { /* do something */ }} />

}It makes sense to think that the second one is faster, because every time the render is called, a new function is created in the first one, while the second one only assigns a value inside the loop. Although there is indeed a performance difference between them, this difference may be smaller than you think.

Finally, let’s take a look at one last example:

// A

var obj = {a:1, b:2, ...} // 非常大的 object

// B

var obj = JSON.parse('{"a": 1, "b": 2, ...}') // JSON.parse 搭配很長的字串If A and B both represent a very large object, which one is faster?

Intuitively, it seems that A is faster, because B seems to be redundant, first converting the object to a string and then passing it to JSON.parse, adding an extra step. But in fact, B is faster, and more than 1.5 times faster.

Many things may seem the same at first glance, but in reality, they can be quite different. Intuition is one thing, but when it comes to the underlying optimizations done by compilers or even the operating system, taking those into consideration can lead to a completely different outcome.

Just like the topic discussed in this article, it may seem intuitive that let is slower than var. However, in cases where closures are not needed, there is no difference between the two.

To address these issues, you can certainly make guesses, but you should know that they are just that - guesses. To find out the correct answer, a more scientific approach is necessary, rather than just relying on “I think”.

Comments