Introduction

If there is one concept in JavaScript that is important and commonly used but often confused by beginners, it is undoubtedly “Asynchronous”. Compared to other concepts such as this, closure, prototype, or hoisting, asynchronous is used much more frequently in practical development and is often a pitfall for beginners.

Is asynchronous really that difficult?

I don’t think so. As long as you follow a correct context, you can gradually understand why asynchronous is needed and how it is handled in JavaScript.

I actually wrote about a similar topic four years ago, but looking back now, it was not well written. Therefore, four years later, I am revisiting this topic and hoping to write a better quality article to clarify the concept of asynchronous.

Before writing this article, I referred to the official documentation of Node.js and found that it actually explains asynchronous quite well. Therefore, this article will start with a similar approach to discuss this issue. If you don’t know Node.js, it’s okay, I will provide a brief introduction below.

It is recommended that you have a basic understanding of JavaScript, know how to use JavaScript to manipulate the DOM, and know what ajax is before reading this article.

Let’s get started!

Basic Introduction to Node.js

JavaScript is a programming language with its own specifications, such as using var to declare variables, using if else for conditional statements, or using function to declare functions. These are all parts of the JavaScript language itself.

Since I mentioned “parts of the programming language itself” above, it means that there are also things that “do not belong to the JavaScript language”.

For example, document.querySelector('body') allows you to get the DOM object of the body and manipulate it, and the changes will be immediately reflected on the browser screen.

Where does this document come from? It is actually provided by the browser to JavaScript, so that JavaScript can communicate with the browser through this document object to manipulate the DOM.

If you look at the ECMAScript documentation, you will find that there is no mention of document at all, because it is not part of the programming language itself, but is provided by the browser.

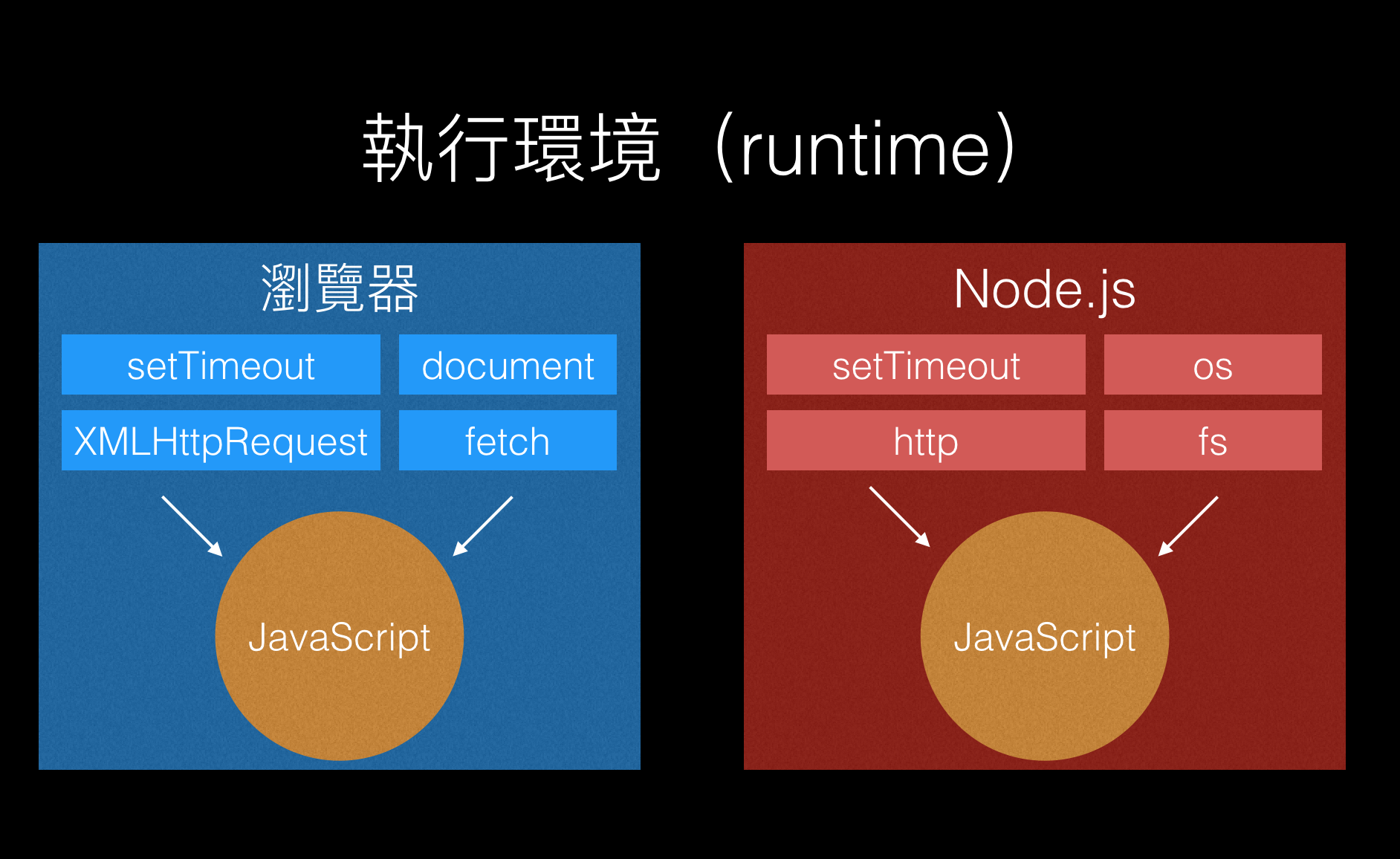

If you run JavaScript on a browser, we can call the browser the “runtime environment” of JavaScript, because JavaScript runs on it, which is very reasonable.

In addition to document, things like setTimeout and setInterval for timing, XMLHttpRequest and fetch for ajax, are all provided by the browser runtime environment.

If you switch to another runtime environment, will there be different things to use? In addition to the browser, are there other JavaScript runtime environments?

As it happens, there is, and you have heard of it, it’s called Node.js.

Many people think that it is a JavaScript library, but it is not, but it is easy to misunderstand because of the last two letters .js. If you feel that those two letters have been misleading you, you can temporarily call it Node.

Node.js is actually a runtime environment for JavaScript, as it says on its official website:

Node.js® is a JavaScript runtime built on Chrome’s V8 JavaScript engine.

So JavaScript code can choose to run in the browser, which can manipulate the screen or send requests through the environment provided by the browser, or it can choose to run on the Node.js environment, which provides different things.

So what does Node.js provide? For example, fs, which stands for file system, is an interface for controlling files, so JavaScript can read and write files on the computer! It also provides the http module, which allows JavaScript to write a server!

Please refer to the diagram below for details:

It can be seen clearly that when JavaScript is executed in different environments, the things that can be used are also different, depending on what the execution environment provides. Sharp-eyed people may notice that setTimeout appears in both environments in the above figure. Why is that?

Because both environments consider the timer function important, they both provide the setTimeout function for developers to use. Although the functions on the two environments are exactly the same, it should be noted that because the execution environments are different, the implementation and principles behind them are also different.

In addition, different execution environments will have different execution methods. For example, for browsers, you can use <script src="index.js"> to import a JavaScript file and execute it in the browser. For Node.js, you must first install the Node.js execution environment on your computer, and then use the node index.js command in the CLI to execute it.

Let’s summarize the current key points:

- JavaScript is just a programming language and needs to be used with things provided by the execution environment, such as

setTimeout,document, etc. - The two most common JavaScript execution environments are browsers and Node.js.

- Different execution environments provide different things. For example, Node.js provides the http module, which allows JavaScript to write a server, but browsers do not provide such things.

Next, we will start to introduce synchronous and asynchronous from the perspective of Node.js.

Blocking and Non-Blocking

As mentioned earlier, Node.js provides an interface for controlling files, allowing us to write JavaScript to read and write files. Let’s take a look at some actual code:

const fs = require('fs') // 引入內建 file system 模組

const file = fs.readFileSync('./README.md') // 讀取檔案

console.log(file) // 印出內容The above code first imports the built-in module fs provided by Node.js, and then uses fs.readFileSync to read the file, and finally prints the contents of the file using console.log.

(Note: Actually, what is printed above is a Buffer. The complete code should be file.toString('utf8') to print the file content. But because this small detail does not affect understanding, it is deliberately ignored in the sample code.)

It seems like there is no problem… right?

If the file is small, there is indeed no problem, but what if the file is very large? For example, the file is 777 MB, and it may take a few seconds or even longer to read such a large file into memory.

When reading the file, the program will stop at the second line, wait for the file to be read, and then put the contents of the file into the file variable and execute the third line console.log(file).

In other words, the fs.readFileSync method “blocks” the execution of subsequent instructions. At this time, we say that this method is blocking, because the execution of the program will block here until it is executed and the return value is obtained.

If some subsequent instructions are completely unrelated to reading the file, such as finding a certain string in the file, etc., then this method is actually not suitable.

For example, if we want to read a file and find even numbers between 1 and 99999999:

const fs = require('fs')

const file = fs.readFileSync('./README.md') // 在這邊等好幾秒才往下執行

console.log(file)

const arr = []

for (let i = 2; i <= 99999999; i+=2) {

arr.push(i)

}

console.log(arr)The above code will wait for a few seconds on the line that reads the file, and then execute the next part below, calculate the even numbers between 1 and 99999999, and print them out.

These two things have nothing to do with each other. Why should printing even numbers wait for the file to be read? Can’t these two things be done at the same time? Isn’t that more efficient?

There is indeed such a thing. There is another way to perform these two things at the same time.

The problem with readFileSync is that it will block the execution of subsequent code, just like when I go to a nearby braised food stall to buy braised food, I have to wait there after ordering, and I can’t go anywhere because I want to eat hot braised food. If I go home and come back every ten minutes, the braised food may have cooled down. I don’t want that. I didn’t buy ice braised food.

So I can only stand there and wait, feeling cold, in order to get the freshly cooked braised food as soon as possible.

The opposite of blocking is called non-blocking, which means that it will not block the execution of subsequent code, just like when I order food in the food court of a department store, the store will give me a pager (the fast food restaurant that is the main body of the red tea also has it). After I get the pager, I can go back to my seat and wait, or I can go shopping if I want to. When the meal is ready, the pager will ring, and I can go to the store to pick up the meal without waiting in place.

When it comes to reading files, how is it done in a non-blocking way? If subsequent code execution is not blocked, how can I get the contents of the file?

Just like how food delivery apps need to use a notification system to inform customers when their orders are ready, in JavaScript, to achieve non-blocking behavior, you need to provide a callback function to the file reading method so that it can notify you when the file has finished reading. In JavaScript, functions are suitable as callback functions!

This means “when the file has finished reading, please execute this function and pass the result into it”, and this function is called a callback function. Doesn’t the name sound perfect?

In addition to the blocking method readFileSync, the fs module in Node.js also provides another method called readFile, which is the non-blocking version of reading files that we mentioned earlier. Let’s take a look at what the code looks like:

// 讀取內建 fs 模組

const fs = require('fs')

// 定義讀取檔案完成以後,要執行的 function

function readFileFinished(err, data) {

if (err) {

console.log(err)

} else {

console.log(data)

}

}

// 讀取檔案,第二個參數是 callback function

fs.readFile('./README.md', readFileFinished);It can be seen that the usage of readFile is similar to that of readFileSync, but the difference is:

readFilehas an additional parameter, which is a function that needs to be passed in.readFileSynchas a return value, which is the file content, butreadFiledoes not seem to have one.

This corresponds to what I said earlier, that the difference between blocking and non-blocking is that blocking methods will directly return results (and that’s why they block), but non-blocking methods can jump to the next line after executing the function, and the result will be passed into the callback function after the file has finished reading.

In the above code, readFileFinished is the callback function, which is the notification system for food delivery. “When the order is ready, let the notification system ring” is the same as “when the file has finished reading, call the callback function”.

Therefore, the explanation of the line fs.readFile('./README.md', readFileFinished) is simple: “Please read the file ./README.md, and call readFileFinished after reading is complete, and pass the result into it.”

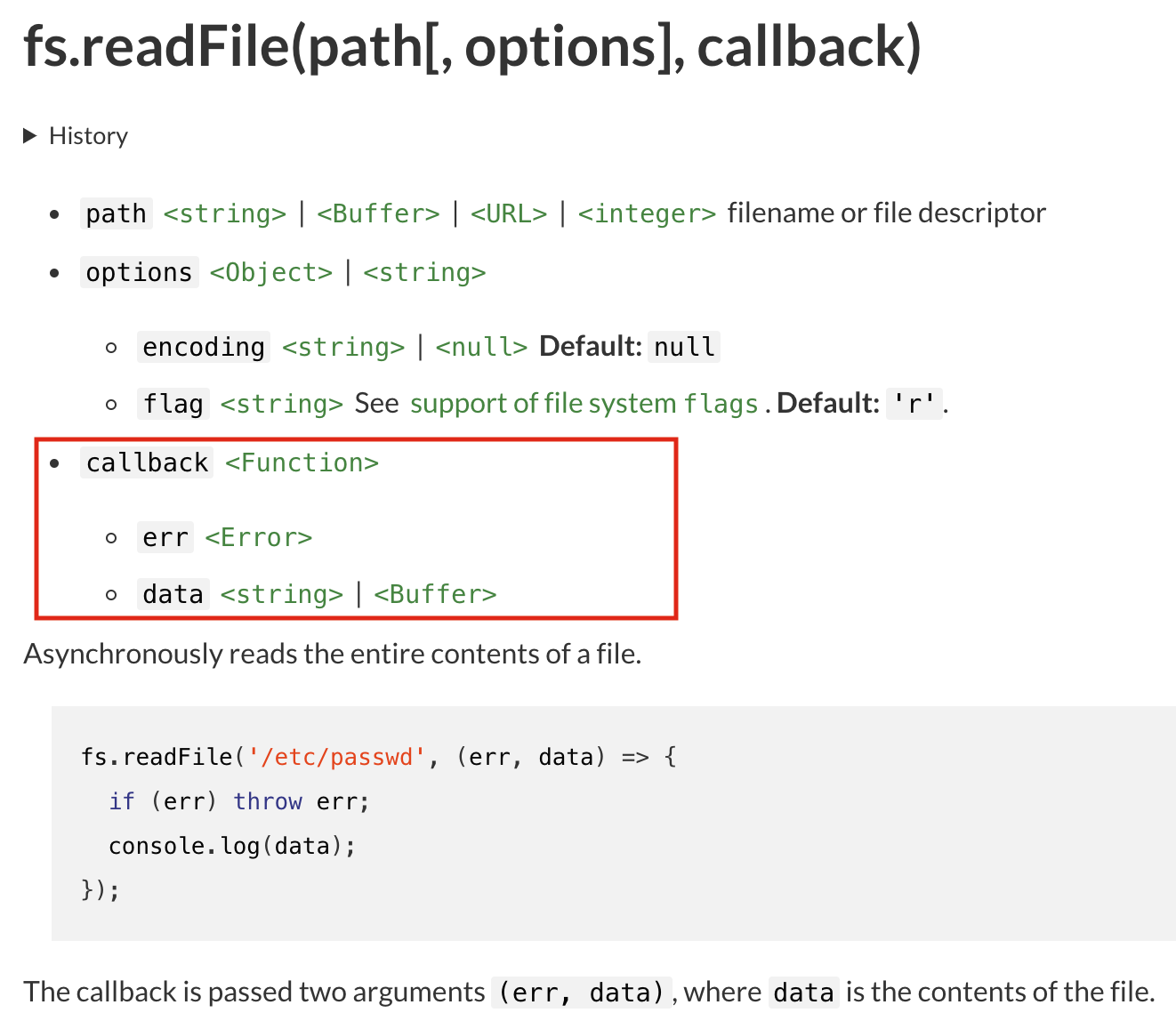

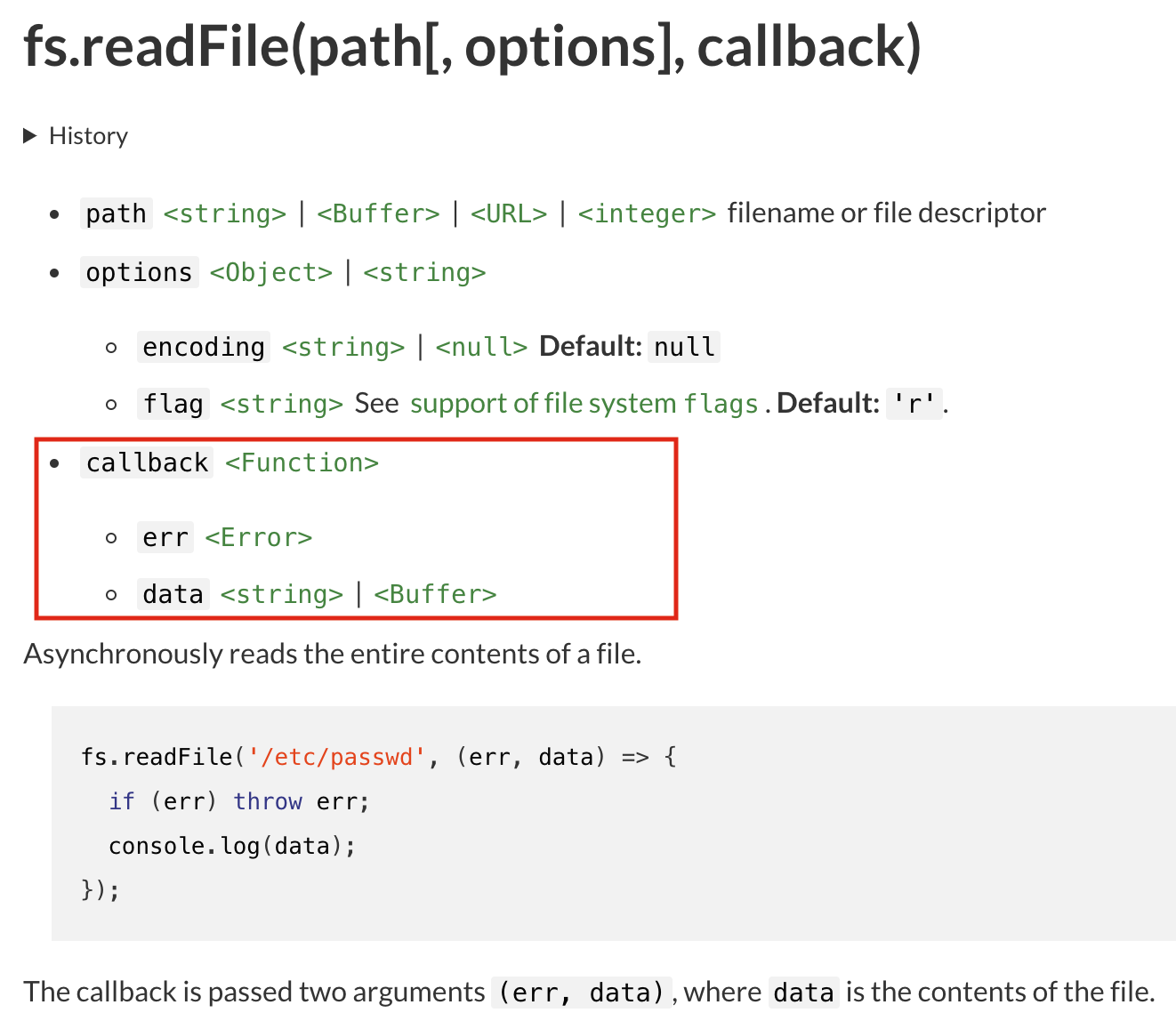

How do I know how the result will be passed in? This depends on the API documentation. For each method, the parameters passed in are different. For readFile, the official documentation is written like this:

It clearly states that the first parameter of the callback is err, and the second parameter is data, which is the file content.

Therefore, fs.readFile simply reads the file in a non-blocking way and calls the callback function after reading is complete, passing the result into it.

Usually, callback functions use the anonymous function syntax to make them simpler. So the more common form is like this:

// 讀取內建 fs 模組

const fs = require('fs')

// 讀取檔案

fs.readFile('./README.md', function(err, data) {

if (err) {

console.log(err)

} else {

console.log(data)

}

});You can think of it as declaring a function directly at the second parameter, without a name, so it is called an anonymous function.

Since readFile is non-blocking, the subsequent code will be executed immediately, so let’s rewrite the even number version we found earlier to be non-blocking:

const fs = require('fs')

/*

原來的阻塞版本:

const file = fs.readFileSync('./README.md') // 在這邊等好幾秒才往下執行

*/

fs.readFile('./README.md', function(err, data) {

if (err) {

console.log(err)

} else {

console.log(data)

}

});

const arr = []

for (let i = 2; i <= 99999999; i+=2) {

arr.push(i)

}

console.log(arr)This way, the system can do other things while waiting for the file to be read, without getting stuck there.

To summarize:

- Blocking means that the program will be stuck on that line until there is a result, such as

readFileSync, which needs to wait for the file to finish reading before executing the next line. - Non-blocking means that the program will not be stuck, but the execution result will not be returned in the return value, but needs to be received through the callback function.

Synchronous and Asynchronous

You may be wondering, “Didn’t you say you were going to talk about synchronous and asynchronous? Why hasn’t it been mentioned yet?”

Actually, we’ve already covered it.

According to the official Node.js documentation:

Blocking methods execute synchronously and non-blocking methods execute asynchronously.

Sync at the end of readFileSync means that this method is synchronous, indicating that it is a synchronous method. readFile, on the other hand, is asynchronous.

If you try to explain it literally in Chinese, it will be very painful, and you will think: “Isn’t synchronization simultaneous? It feels more like non-blocking, but why is it reversed?”

I got inspired from Should programming be synchronous or asynchronous?, which suggests that we just need to explain what “synchronization” means in the field of computers in a different way.

Now, imagine a group of people playing a three-legged race with their feet tied together. If we want them to “move in unison”, that is, to have everyone’s steps synchronized, how do we do it? Of course, everyone needs to coordinate and wait for each other. Those with faster feet need to slow down, and those with slower feet need to speed up. If you have already taken the first step, you have to wait for those who have not taken the first step yet. You can only start taking the second step after everyone has taken the first step.

Therefore, in order for different people to coordinate their steps and try to make everyone’s steps consistent, they must wait for each other, and this is synchronization.

Asynchronous is simple, it means the opposite. Although they are playing a three-legged race, they do not want to wait for each other. Everyone moves at their own pace, so it is possible that the person at the front has already reached the finish line, while the person at the back is still in the middle, because everyone’s steps are not synchronized.

Programming is the same. In the example mentioned earlier, which involves reading files and printing even numbers, synchronization means that everyone needs to coordinate and wait for each other. Therefore, you cannot print even numbers when the file is not yet read. You must wait until the file is read before you can print even numbers.

Asynchronous means that everyone does their own thing. You read your file, and I continue to print my even numbers. It doesn’t matter if everyone’s steps are not synchronized, because we are not synchronized in the first place.

In short, when discussing the issue of synchronous and asynchronous in JavaScript, you can basically equate asynchronous with non-blocking and synchronous with blocking. If you execute a synchronous method (such as readFileSync), it will definitely block; if you execute an asynchronous method (readFile), it will definitely not block.

However, let me add a little bit for you. If you are not discussing this issue in JavaScript but in other contexts, the answer will be different. For example, when you are looking up blocking and non-blocking as well as synchronous and asynchronous, you will definitely come across some information related to system I/O, which I think is a discussion at a different level.

When you are discussing system or network I/O, asynchronous and non-blocking are two different things, and synchronous and blocking are also two different things, with different meanings.

But if our context is limited to discussing the issue of synchronous and asynchronous in JavaScript, blocking is basically synchronous, and non-blocking is asynchronous. The official documentation of Node.js mentioned earlier also mixes these two concepts.

Once we equate these two things, it is easy to understand what is synchronous and what is asynchronous. I will just summarize the key points of the previous paragraph:

- Synchronous means that the program will be stuck on that line until there is a result, such as

readFileSync, which needs to wait for the file to be read before executing the next line. - Asynchronous means that it will not be stuck during execution, but the execution result will not be returned in the return value. Instead, it needs to be received through a callback function.

Synchronous and Asynchronous in Browsers

So far, we have been using Node.js as an example, and now we are finally returning to the more familiar front-end browser.

When writing JavaScript in the front-end, there is a very common need, which is to connect with the backend API to retrieve data. Suppose we have a function called getAPIResponse, which can call the API to retrieve data.

The synchronous version looks like this:

const response = getAPIResponse()

console.log(response)What happens when it is synchronous? It will block the subsequent execution. Therefore, if the API server specification is poor and it takes 10 seconds to retrieve data, the entire JavaScript engine must wait for 10 seconds before executing the next instruction. When we use Node.js as an example, sometimes waiting for 10 seconds is acceptable, because only the person executing this program needs to wait for 10 seconds. I can go and browse Instagram and come back.

But can the browser accept waiting for 10 seconds?

Think about it. If the execution of JavaScript is frozen there for 10 seconds, it means that the thread that executes JavaScript (thread) is frozen for 10 seconds. In the browser, the main thread responsible for executing JavaScript is called the main thread, and the main thread responsible for processing and rendering the screen is also the main thread. In other words, if this thread is frozen for 10 seconds, it means that no matter how you click the screen, there will be no response, because the browser does not have the resources to handle these other things.

In other words, your screen looks like it has crashed.

(If you don’t know what a thread is, please refer to: Inside look at modern web browser, it is recommended to start reading from part1, and the main thread is in part3.)

Take a real-life example to illustrate: if you go to a store near your house to order a chicken cutlet, you have to wait on-site after ordering. If your friend comes to visit you and rings your doorbell, you won’t be able to respond because you’re not at home. Your friend will have to wait until you come back with the chicken cutlet to open the door for them.

However, if the store introduces an online queuing system, you can check the status of the chicken cutlet production through an app after ordering. You can go home and wait for the chicken cutlet while watching TV. If your friend comes and rings the doorbell, you can open the door for them directly, and they don’t have to wait.

“Waiting for the chicken cutlet” refers to “waiting for the response,” “opening the door for your friend” refers to “responding to the screen,” and “you” refer to the “main thread.” When you are busy waiting for the chicken cutlet, you cannot open the door for your friend.

You can create a simple demo to verify the frozen screen part yourself. Just create an HTML file like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

</head>

<body>

<div>凍結那時間,凍結初遇那一天</div>

</body>

<script>

var delay = 3000 // 凍結 3 秒

var end = +new Date() + delay

console.log('delay start')

while(new Date() < end) {

}

console.log('delay end')

</script>

</html>The principle is that the while loop inside will continuously check whether the time has arrived. If it hasn’t, it will continue to wait, so it will block the entire main thread. You can also refer to the gif below. Before the “delay end” appears, no matter how you highlight the text, it won’t work until the “delay end” appears:

Can you accept a frozen screen? Even if you can, your boss or client cannot accept it. Therefore, it is impossible to perform such time-consuming operations synchronously in the front-end. Since it needs to be changed to asynchronous, according to what we learned before, it needs to be changed to use a callback function to receive the result:

// 底下會有三個範例,都在做一模一樣的事情

// 主要是想讓初學者知道底下三個是一樣的,只是寫法不同

// 範例一

// 最初學者友善的版本,額外宣告函式

function handleResponst() {

console.log(response)

}

getAPIResponse(handleResponst)

// 範例二

// 比較常看到的匿名函式版本,功能跟上面完全一樣

getAPIResponse(function(err, response) {

console.log(response)

})

// 範例三

// 利用 ES6 箭頭函式簡化過後的版本

getAPIResponse((err, response) => {

console.log(response)

})The full name of AJAX is “Asynchronous JavaScript and XML.” Asynchronous means sending the request asynchronously.

Here, we used a hypothetical function getAPIResponse for demonstration purposes, mainly to illustrate that “network operations cannot be performed synchronously in the front-end.” Next, let’s take a look at what the actual code for calling the backend API in the front-end will look like:

var request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open('GET', 'https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users/1', true);

request.onload = function() {

if (this.status >= 200 && this.status < 400) {

console.log(this.response)

}

};

request.send();You may wonder: “Huh? Why does it look different? Where is the callback function?”

The callback function here is the function after request.onload = , and the meaning of this line is: “When the response comes back, please execute this function.”

At this point, sharp-eyed people may notice: “Huh? Why does request.onload look familiar?”

The callback that is strange but familiar to you

The meaning of the callback function is actually: “When something happens, please use this function to notify me.” Although it may seem unfamiliar at first, you have been using it for a long time.

For example:

const btn = document.querySelector('.btn_alert')

btn.addEventListener('click', handleClick)

function handleClick() {

alert('click!')

}“When something (someone clicks the .btn_alert button) happens, please use this function (handleClick) to notify me.” Isn’t handleClick a callback function?

Or:

window.onload = function() {

alert('load!')

}“When something (the webpage finishes loading) happens, please use this function (anonymous function) to notify me.” Isn’t this also a callback function?

Here’s one last example:

setTimeout(tick, 2000)

function tick() {

alert('時間到!')

}“When something (two seconds have passed) happens, please use this function (tick) to notify me.” It’s the same pattern.

When using a callback function, there is a common mistake that beginners often make, which must be paid special attention to. It has been said that the parameter passed in is a callback function, which is a “function,” not the result of executing the function (unless your function will return a function after execution, which is another matter).

For example, the standard error example would look like this:

setTimeout(tick(), 2000)

function tick() {

alert('時間到!')

}

// 或者是這樣

window.onload = load()

function load() {

alert('load!')

}tick is a function, and tick() executes a function and uses the return result as a callback function. In short, it’s like this:

// 錯誤範例

setTimeout(tick(), 2000)

function tick() {

alert('時間到!')

}

// 上面的錯誤範例等同於

let fn = tick()

setTimeout(fn, 2000)

function tick() {

alert('時間到!')

}Since tick will return undefined after execution, the setTimeout line can be seen as setTimeout(undefined, 2000), which has no effect at all.

Writing a function as a function call will result in the screen still displaying the words “Time’s up!” but two seconds have not yet passed. Because writing it this way is equivalent to executing the tick function first.

The example of window.onload is the same and can be seen as follows:

// 錯誤範例

window.onload = load()

function load() {

alert('load!')

}

// 上面的錯誤範例等同於

let fn = load()

window.onload = fnSo the load function will be executed before the webpage is fully loaded.

To reiterate, tick is a function, and tick() is executing the function. These two have completely different meanings.

Let’s review the key points:

- The main thread that executes JavaScript in the browser is also responsible for rendering the screen. Therefore, asynchronous is more important and necessary, otherwise the screen will freeze while waiting.

- The meaning of the callback function is actually: “When something happens, please use this function to notify me.”

fnis a function, andfn()is executing the function.

Parameters of the Callback Function

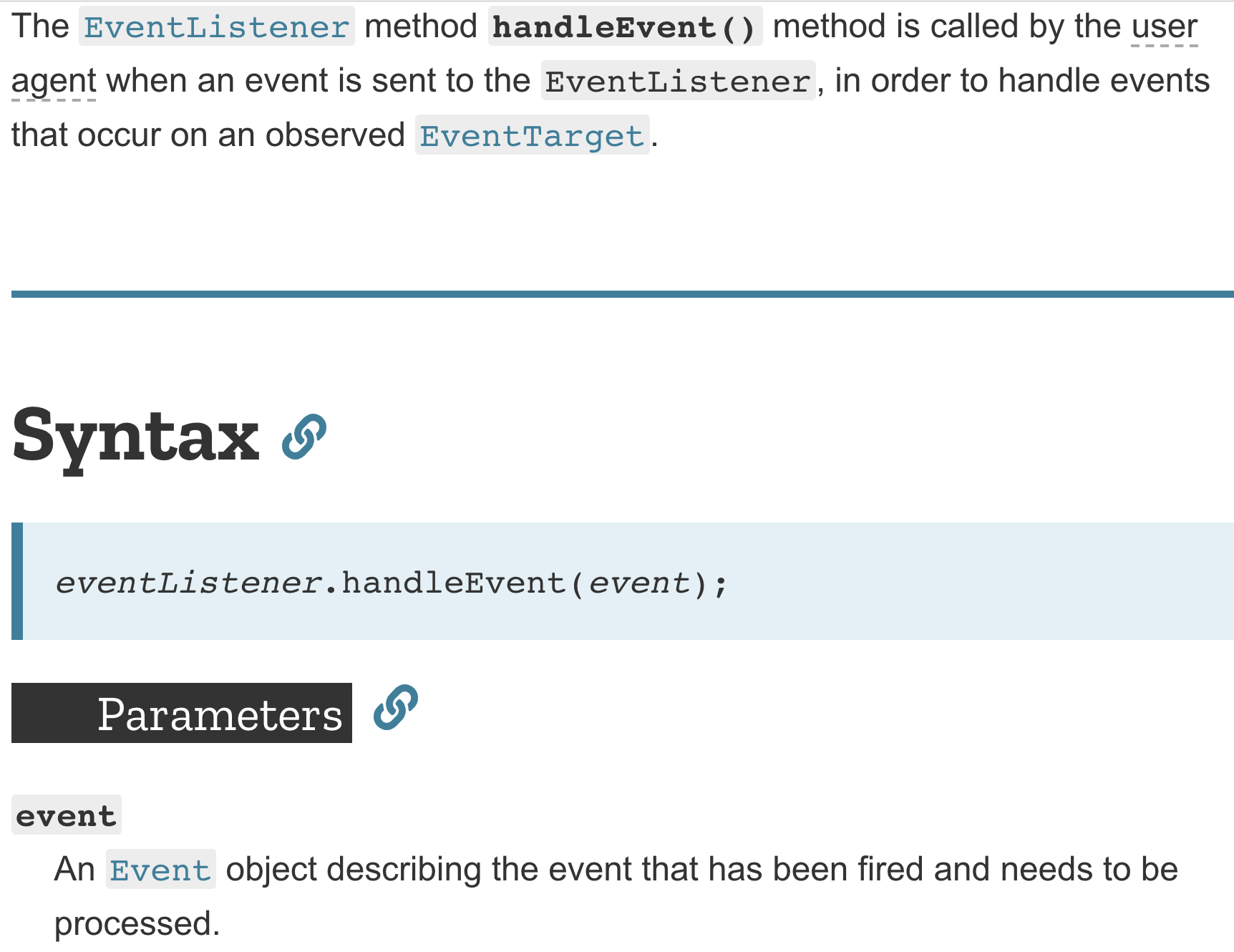

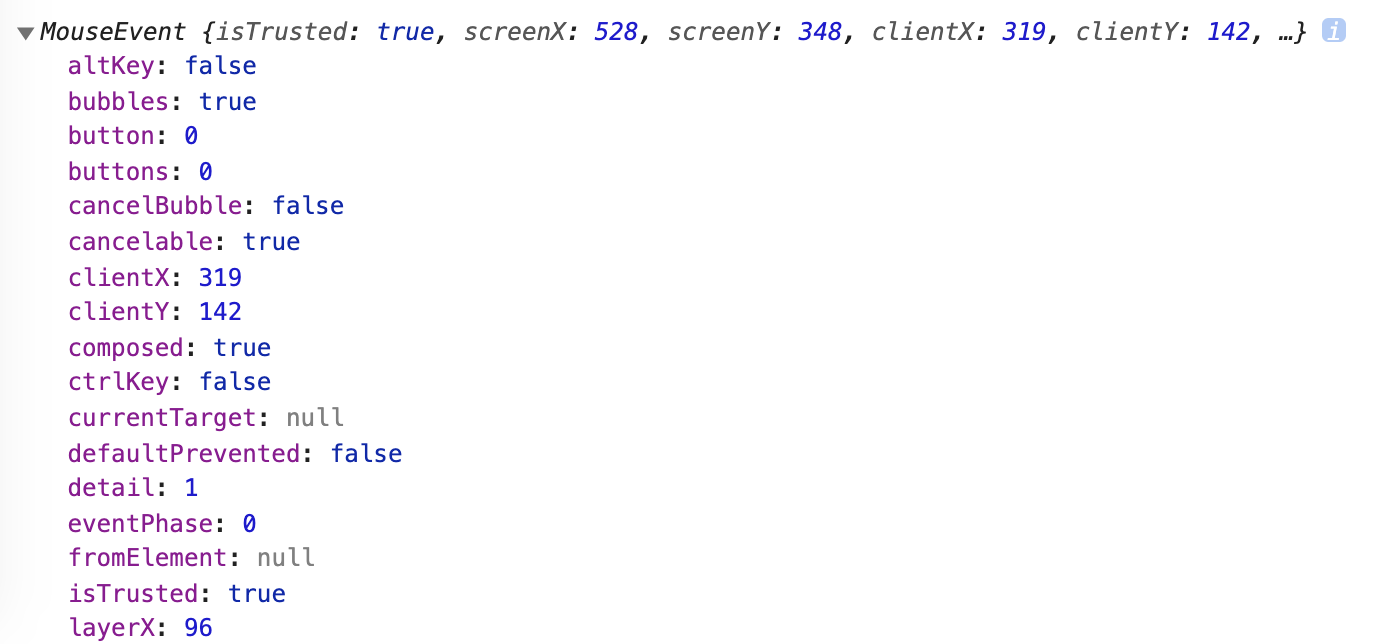

As mentioned earlier, you need to refer to the documentation to know what parameters the callback function needs. Let’s take the following button click as an example:

const btn = document.querySelector('.btn_alert')

btn.addEventListener('click', handleClick)

function handleClick() {

alert('click!')

}From the MDN documentation, you can see that it is written like this:

An object called event will be passed in, and this object describes the event that occurred. It sounds abstract, but we can actually experiment with it:

const btn = document.querySelector('.btn_alert')

btn.addEventListener('click', handleClick)

function handleClick(e) {

console.log(e)

}When we click this button, we can see that the console prints an object with a lot of properties:

If you look closely, you will find that this object actually describes the “click” just now, for example, clientX and clientY actually represent the coordinates of the click just now. The most commonly used one, which you must have heard of, is e.target, which can get the DOM object where the click event occurred.

However, at this point, beginners may have a question: “The documentation clearly states that the parameter passed in is called event, why can you use e?”

This is because when a function sends and receives parameters, it only cares about the “order”, not the name in the documentation. The name in the documentation is only for reference, and does not mean that you must use that name to receive it. The function is not so intelligent and will not judge which parameter it is based on the variable name.

So you can name your callback function parameters whatever you want, handleClick(e), handleClick(evt), handleClick(event), or handleClick(yoooooo) can all get the event object passed by the browser, just different names.

What parameters the callback function will receive depends on the documentation. If there is no documentation, no one knows what parameters the callback will receive.

Although this is the case, in many places, parameters follow a convention.

Error First Convention of Callbacks

In addition to callbacks, there is another huge difference between synchronous and asynchronous, which is error handling.

Going back to the synchronous file reading example we mentioned at the beginning:

const fs = require('fs') // 引入內建 file system 模組

const file = fs.readFileSync('./README.md') // 讀取檔案

console.log(file) // 印出內容If the file ./README.md does not exist, an error message will be printed in the console after execution:

fs.js:115

throw err;

^

Error: ENOENT: no such file or directory, open './README.md'

at Object.openSync (fs.js:436:3)

at Object.readFileSync (fs.js:341:35)To handle this kind of error, you can use the try...catch syntax to wrap it:

const fs = require('fs') // 引入內建 file system 模組

try {

const file = fs.readFileSync('./README.md') // 讀取檔案

console.log(file) // 印出內容

} catch(err) {

console.log('讀檔失敗')

}When we wrap it with try...catch, we can handle the error. In the example above, “Reading file failed” will be output.

But if we switch to the asynchronous version, things are a bit different. Please take a look at the example code below first:

const fs = require('fs') // 引入內建 file system 模組

try {

// 讀取檔案

fs.readFile('./README.md', (err, data) => {

console.log(data) // 印出內容

})

} catch(err) {

console.log('讀檔失敗')

}After execution, the console has no response at all! Obviously, an error occurred, but it was not caught. Why is this?

This is another huge difference between synchronous and asynchronous.

In the synchronous version, we wait for the file to be read before executing the next line, so if there is an error when reading the file, the error will be thrown out, and we can try…catch to handle it.

But in the asynchronous version, the fs.readFile function only does one thing, which is to tell Node.js: “Go read the file, call the callback function after reading.” After doing this, it continues to execute the next line.

So we have no idea what happened when reading the file.

For example, this is like the inside and outside of a restaurant. Suppose I am responsible for the outside, and someone orders a bowl of beef noodles. I will shout to the kitchen: “A bowl of beef noodles!” and continue to serve the next customer. Did the kitchen really start making beef noodles? I don’t know, but it should. If the beef is sold out and cannot be made, I will not know when I shout.

So how will I know?

Assuming the beef is really sold out, the back kitchen will come to me proactively and tell me that the beef is sold out. Only then will I know that the beef is sold out.

This is just like the asynchronous example. That line is only responsible for telling the system to “read the file”. If something happens, you must actively tell it and use the callback method to pass it.

Let’s review the Node.js readFile document mentioned at the beginning:

The callback will have two parameters, the first is err, and the second is data, so you know how err came about. Whenever there is an error in reading the file, such as the file does not exist, the file exceeds the memory size, or the file does not have permission to open, etc., it will be passed in through this err parameter. You cannot catch this error with try…catch.

Therefore, when we perform something asynchronously, there are two things we will definitely want to know:

- Whether there is an error, and if so, what is the error

- The return value of this thing

For example, when reading a file, we want to know if there is an error and also want to know the file content. Or when operating a database, we want to know if the command is wrong and also want to know what the returned data is.

Since we always want to know these two things asynchronously, it means that there will be at least two parameters, one is an error, and the other is a return value. The “error first” in the subtitle means that the error is usually placed in the first parameter “according to convention”, and other return values are placed in the second and subsequent parameters.

Why?

Because there is only one error, but there may be many return values.

For example, suppose there is a function called getFileStats that will asynchronously fetch the file status and return the file name, file size, file permissions, and file owner. If err is placed as the last parameter, our callback will look like this: function cb(fileName, fileSize, fileMod, fileOwner, err)

I have to write out all the parameters clearly to get err. In other words, if I only want the file name and file size today, and I don’t care about the others, what should I do? There is nothing to do. I still have to write it so long because err is the last one.

If err is placed first, I only need to write: function cb(err, fileName, fileSize), and I don’t need to write the later parameters if I don’t want to take them.

This is why err should be placed at the beginning, because we will always need err, but we may not need all the later parameters. Therefore, whenever you see a callback function, the first parameter usually represents an error message.

So it is very common to see this processing method, first check if there is an error and then do other things:

const fs = require('fs')

fs.readFile('./README.md', (err, data) => {

// 如果錯誤發生,處理錯誤然後返回,就不會繼續執行下去

if (err) {

console.log(err)

return

}

console.log(data)

});Finally, there are three points to supplement. The first point is that “error first” is just a “convention”. The actual parameters passed depend on the document. You can also write an API that puts the error as the last parameter (but you shouldn’t do that).

The second point is that although it is asynchronous, it is still possible to catch errors using try catch, but the “type” of the error is different, for example:

const fs = require('fs')

try {

// 讀取檔案

fs.readFile('./README.md')

} catch(err) {

console.log('讀檔失敗')

console.log(err)

// TypeError [ERR_INVALID_CALLBACK]: Callback must be a function

}The error caught here is not the error generated by “reading the file”, but the error generated by “calling the read file this function”. Using the restaurant example mentioned earlier, it is like you know that the beef noodles are sold out when the customer orders, so you don’t need to ask the back kitchen, you can directly tell the customer: “Sorry, our beef noodles are sold out. Would you like to consider ordering something else?”

The last point I want to add is that some people may ask: “Then why don’t setTimeout or event listeners have the err parameter?”

That’s because the application scenarios of these few things are different.

The meaning of setTimeout is: “After n seconds, please call this function”, and the meaning of the event listener is: “When someone clicks the button, please call this function”.

These two things will not cause errors.

But when using readFile to read a file, errors may occur when reading the file; and XMLHttpRequest has onerror to catch asynchronous errors.

To summarize:

- The parameters of the callback function are the same as those of the general function, and they are based on “order” rather than name, and they are not so smart.

- According to convention, the first parameter of the callback function is usually err, which is used to tell you whether an error has occurred (according to the first point, you can call it e, error, or fxxkingError).

- Although it is asynchronous, it is still possible to catch errors using try catch, but that means that an error occurred when “calling the asynchronous function”.

Understanding the last puzzle of asynchronous: Event loop

We have talked so much about asynchronous, have you ever thought about how asynchronous is done?

Isn’t it often heard that JavaScript is single-threaded and only one thread is running? But if it is really single-threaded, how can it achieve asynchronous?

If you want to understand how asynchronous operations work, I highly recommend this video: What the heck is the event loop anyway? | Philip Roberts | JSConf EU. Everyone who has watched it has praised it.

Once you’ve watched the video, you’ll understand how asynchronous operations work. Since the video is so well done, I’ll just summarize the key points below. Please watch the video before reading on. If you haven’t watched it yet, please do so.

In the execution of a program, there is something called the call stack, which basically records the resources needed for each function to execute, as well as the order in which functions are executed.

For example, consider the following code:

function a() {

return 1

}

function b() {

a()

}

function c() {

b()

}

c()We first call c, so the call stack looks like this (the example below will grow upwards):

cc calls b:

b

cb calls a:

a

b

cAfter a is executed, which function should it return to? It’s simple, remove a from the call stack, and the one on top is the one to return to:

b

cThen b is executed and removed from the call stack:

cFinally, c is executed, the call stack is cleared, and the program ends.

The call stack is where the order of function execution and other necessary things are recorded, and the well-known error stack overflow refers to when the stack is too full, such as when you recursively call a function 100,000 times and the stack can’t store so many things, resulting in a stack overflow error.

JavaScript’s “only one thread” means that there is only one call stack, so only one thing can be executed at a time.

So how does asynchronous programming work?

I only said that “JavaScript can only do one thing at a time,” but I didn’t say that “the execution environment is the same.”

For example, when reading a file, we can explain the asynchronous file reading code as “ask the system to read the file, and after the file is read, pass the result back through the callback function.” Behind the scenes, Node.js can use another thread to read the file, which is completely fine.

setTimeout is also the same. setTimeout(fn, 2000) just tells the browser, “Call the function fn after 2 seconds,” and the browser can use another thread to time it, rather than using the main thread.

The key is, when these other threads are done, how do they get back to the main thread? Because only the main thread can execute JavaScript, it must be returned, otherwise it won’t run.

This is what the event loop does.

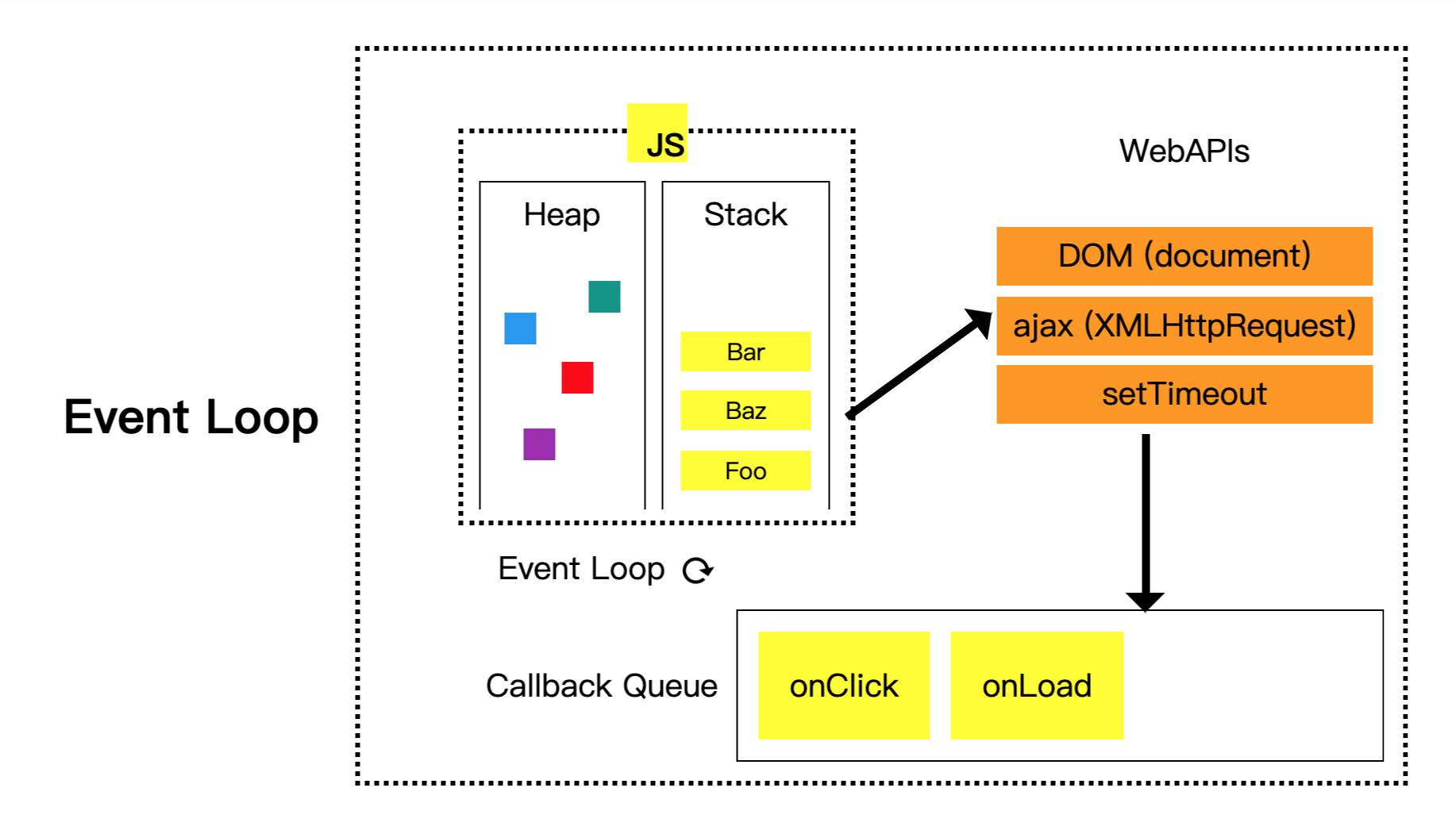

Let’s start with a classic picture:

(Image source: Understanding Event Loop, Call Stack, Event & Job Queue in Javascript with a screenshot of codepen)

Let’s first explain the right side. Suppose we execute the code setTimeout(fn, 2000). We first put setTimeout(fn, 2000) into the call stack to execute, and then setTimeout belongs to the Web API, so it will tell the browser, “Hey, set a timer for me, call fn after 2000 milliseconds,” and then it ends and is popped out of the call stack.

When the browser’s timer is up, it will put fn into the callback queue. Why is there a queue here? Because there may be many callback functions waiting to be executed, so there needs to be a queuing mechanism for everyone to line up here, one by one, so it’s called a callback queue, not a callback array or callback stack.

Then comes the key event loop, which plays a very simple role, which can be explained in plain language:

Continuously detect whether the call stack is empty. If it is empty, put the things in the callback queue into the call stack.

From a programming perspective, the reason why the event loop is called a loop is because it can be represented like this:

while(true) {

if (callStack.length === 0 && callbackQueue.length > 0) {

// 拿出 callbackQueue 的第一個元素,並放到 callStack 去

callStack.push(callbackQueue.dequeue())

}

}That’s it, it’s that simple.

It’s like many famous museums have crowd control. You have to buy a ticket first and then queue up. Then the guard at the door will let the people in the queue in when they see that the people in front have already moved on to the next attraction.

while(true) {

if (博物館入口沒有人 && 排隊的隊伍有人) {

放人進去博物館()

}

}The key point to remember here is that “asynchronous callback functions are first placed in the callback queue and are only thrown into the call stack by the event loop when the call stack is empty.”

The event loop is like a person who only talks and doesn’t do anything. It is not responsible for executing the callback function, it only helps you throw the function into the call stack, and the main thread of JavaScript is the one that actually executes it.

After understanding the event loop mechanism, we can explain asynchronous behavior. The video has already explained it clearly, so I won’t go into too much detail. I’ll just give a common example:

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('0ms')

}, 0)

console.log('hello')Will “hello” be printed first, or will “0ms” be printed first, or is it uncertain?

If your answer is not “hello will be printed first”, it means that you haven’t understood the event loop mechanism, so please go back and watch the video again.

The callback function in the above example will be placed in the callback queue after 0ms, but please note that the call stack is not empty at this time, so console.log('hello') will be executed first. After it is executed, the call stack is cleared, and then the event loop throws the callback into the call stack and then executes console.log('0ms') inside the callback.

So the output order is guaranteed to be “hello” first, followed by “0ms”.

Finally, a few small supplements. The first is that passing 0 to setTimeout means “execute as soon as possible”, but it may not trigger after 0ms, it may be 4ms or longer. For details, please refer to: MDN: Reasons for delays longer than specified

The second supplement is that the event loop actually has a small detail, which is that the callback queue is also divided into two types: macro tasks and micro tasks, but this is a bit complicated, so I’ll talk about it later.

The third supplement is that although both Node.js and browsers have event loops, just like they both have setTimeout, the underlying principles and implementations are different. They are generally the same, but the details are different.

The fourth supplement is that the statement “only the main thread can execute JavaScript” is not correct, because there is a Web Worker in the browser that can be used.

Asynchronous Quiz

After understanding the principle of the event loop for asynchronous operations, you should be quite familiar with the execution of asynchronous operations. Below, I will give some questions to verify whether you really understand:

1. Event Website

Xiao Ming is a front-end engineer at a website that specializes in events. He was assigned a task by his supervisor to add a piece of code to call the backend API to get whether the event has started, and only go to the event page if it has started, otherwise do nothing.

Assuming that getAPIResponse is an asynchronous function that uses ajax to call the API and then gets the result, and the /event API returns JSON format data, where the started boolean field represents whether the event has started.

So Xiao Ming wrote the following code:

// 先設一個 flag 並且設為 false,表示活動沒開始

let isEventStarted = false

// call API 並取得結果

getAPIResponse('/event', response => {

// 判斷活動是否開始並設置 flag

if (response.started) {

isEventStarted = true

}

})

// 根據 flag 決定是否前往活動頁面

if (isEventStarted) {

goToEvent()

}Question: Is there any problem with this code? If so, where is the problem?

2. Waiting Slowly

After completing the event website, Xiao Ming felt that he still wasn’t very familiar with asynchronous operations, so he wanted to practice and wrote the following code:

let gotResponse = false

getAPIResponse('/check', () => {

gotResponse = true

console.log('Received response!')

})

while(!gotResponse) {

console.log('Waiting...')

}

The meaning is that “waiting” will be continuously printed before the ajax response comes back, and it will stop only after receiving the response.

Question: Can the above code meet Xiao Ming’s needs? If not, please explain why.

3. Strange Timer

The supervisor assigned Xiao Ming to fix a bug in the company’s code. He found this code block:

setTimeout(() => {

alert('Welcome!')

}, 1000)

// 後面還有其他程式碼,這邊先略過What is the bug? The timer is supposed to display a message after 1 second, but after executing this code block (note that there is other code below, which is skipped for now), the alert only appears after 2 seconds.

Question: Is this possible? Regardless of whether you think it is possible or not, please try to explain why.

4. Execution Order Test

a(function() {

console.log('a')

})

console.log('hello')Question: What is the final output order? Is it “hello” then “a”, or “a” then “hello”, or is it uncertain?

Answer: 1. Event Website

The answer is problematic. This code block mixes synchronous and asynchronous code, which is the most common mistake.

The event loop will only put the callback into the call stack when the call stack is empty. Therefore, the code that checks isEventStarted will be executed first. When this code is executed, even though the response has returned, the callback function is still waiting in the callback queue. Therefore, when checking isEventStarted, it will always be false.

The correct method is to put the logic for checking whether the event is started inside the callback, which ensures that the response is received before checking:

// call API 並取得結果

getAPIResponse('/event', response => {

// 判斷活動是否開始並設置 flag

if (response.started) {

goToEvent()

}

})Answer: 2. Wait Slowly

The answer is no.

Remember the condition of the event loop? “When the call stack is empty, put the callback into the call stack.”

while(!gotResponse) {

console.log('Waiting...')

}This code block will execute continuously, becoming an infinite loop. Therefore, the call stack is always occupied, and the things in the callback queue cannot be put into the call stack.

Therefore, regardless of whether Xiao Ming’s original code has received a response or not, it will only print “waiting” continuously.

Answer: 3. Strange Timer

The answer is possible.

WebAPI will put the callback into the callback queue after one second. So why does it take two seconds to execute? Because the call stack is occupied for one second.

As long as the code below setTimeout does a lot of things and occupies one second, the callback will be put into the call stack after one second, for example:

setTimeout(() => {

alert('Welcome!')

}, 1000)

// 底下這段程式碼會在 call stack 佔用一秒鐘

const end = +new Date() + 1000

while(end > new Date()){

}Therefore, setTimeout can only guarantee that it will execute “at least” after 1 second, but cannot guarantee that it will execute exactly after 1 second.

Answer: 4. Execution Order Test

The answer is uncertain.

Because I didn’t say whether a is synchronous or asynchronous, don’t assume it’s asynchronous just because there is a callback.

My a can be implemented like this:

function a(fn) {

fn() // 同步執行 fn

}

a(function() {

console.log('a')

})

console.log('hello')The output will be “a” then “hello”.

It can also be implemented like this:

function a(fn) {

setTimeout(fn, 0) // 非同步執行 fn

}

a(function() {

console.log('a')

})

console.log('hello')The output will be “hello” then “a”.

Conclusion

To understand asynchronous programming, you must take it step by step and not try to rush it.

This is also why the title is called “Become a Callback Master First”, because you must have a certain level of proficiency with callbacks before moving on to the next stage, which will make it much easier.

This article mainly aims to establish several important concepts for everyone:

- What is blocking? What is non-blocking?

- What is synchronous? What is asynchronous?

- What is the difference between synchronous and asynchronous?

- Why do we need asynchronous programming?

- What is a callback?

- Why do we need callbacks?

- The error-first convention of callbacks

- What is the event loop? What does it do?

- What are the common pitfalls of asynchronous programming?

If you can fully understand this article and thoroughly understand the quiz at the end, I believe you should have no problem understanding asynchronous programming, and implementation will be much smoother. After understanding the basics of asynchronous programming and callbacks, the next article will discuss the problems and solutions encountered when using callback functions: Promises, and also briefly mention the newer syntax async/await.

(There is currently no sequel, but I will add it when it is available.)

References:

Comments