Preface

Supplement on June 9, 2021:

Thanks to the reader blackr1234 for leaving a comment. This article was published in November 2018, and the output results of the code below are probably based on Node.js v8.17.0, so the output of some situations may be different from now. For example, accessing the let variable before declaration, the result at that time was: ReferenceError: a is not defined, and the result using Node.js v14 now is: ReferenceError: Cannot access 'a' before initialization.

Recently, I have been busy with some teaching-related things, and after preparing some materials, I taught my students about hoisting in JavaScript, which is the concept of “lifting”. For example, the following code:

console.log(a)

var a = 10will output undefined instead of ReferenceError: a is not defined. This phenomenon is called Hoisting, and the declaration of the variable is “lifted” to the top.

If you only want to understand the basics of hoisting, it’s almost like this, but later I also taught some knowledge related to let and const. However, the day before I just finished teaching, the next day I immediately saw a related technical article and found that I had taught it wrong. Therefore, I spent some time planning to understand hoisting well.

Many things may not seem like much before you delve into them. You will find that you still have a lot of concepts that you don’t understand when you really jump in and look deeply.

Many people know hoisting, but the degree of understanding is different. I have listed 10 items. If you don’t know any of them, congratulations, this article should bring you some gains.

- You know what hoisting is

- You know that hoisting only lifts declarations, not assignments

- You know the priority of hoisting when function declarations, function parameters, and general variable declarations appear at the same time

- You know that let and const do not have hoisting

- You know that the fourth point is wrong, in fact, there is hoisting, but the expression is different

- You know that there is a concept called TDZ (Temporal Dead Zone) related to the fifth point

- You have read the ES3 specification and know how it is described inside

- You have read the ES6 specification and know how it is described inside

- You know the principle behind hoisting

- You have seen the code compiled by V8

You may ask, “Why do I need to know so deeply? What’s the use?” In fact, I also think that for hoisting, it is enough to know the basics. As long as you declare variables properly, even if you don’t know those, it will not have much impact on daily life or work.

But if you, like me, want to put “proficient in JavaScript” on your resume one day, you cannot escape these things. At the same time, if you are more familiar with these underlying details, you will encounter fewer problems, and you will also understand why hoisting appears. When you want to go further and climb higher on the technical road, I think these details are very important.

Next, let’s take a look at hoisting step by step!

What is hoisting?

In JavaScript, if you try to get the value of a variable that has not been declared, the following error will occur:

console.log(a)

// ReferenceError: a is not definedIt will return an error of a is not defined because you have not declared this variable, so JavaScript cannot find where this variable is, and naturally throws an error.

But if you write like this, something magical happens:

console.log(a) // undefined

var aSince we learned programming, we have learned a concept, “the program runs line by line”. Since it runs line by line, when it reaches the first line, isn’t the variable a not declared yet? Then why doesn’t it throw an error of a is not defined, but outputs undefined?

This phenomenon is called hoisting, which is lifted. The var a in the second line is “lifted” to the top for some reason, so you can “imagine” the above code like this:

var a

console.log(a) // undefinedI will emphasize “imagine” because the position of the code will not be moved, so don’t think of hoisting as JavaScript engine helping you “move” all variable declarations to the top, which is problematic. Its principle has nothing to do with moving code.

Next, there is one thing to pay special attention to, which is that only variable declarations will be hoisted, not assignments. Take a look at the following example:

console.log(a) // undefined

var a = 5You can “imagine” the above code as follows:

var a

console.log(a) // undefined

a = 5You can split the sentence var a = 5 into two steps. The first step is to declare the variable: var a, and the second step is to assign the value: a = 5. Only the variable declaration in the first step will be hoisted, not the assignment in the second step.

At this point, you may think it’s okay, just a little confused. Congratulations, there will be more things to make you even more confused later. Let’s add a few more things and see how complex it can get.

If we do it like this, what will be output?

function test(v){

console.log(v)

var v = 3

}

test(10)Simply put, according to what we just learned, we can transform the above code into the following form:

function test(v){

var v

console.log(v)

v = 3

}

test(10)The answer is undefined! Easy peasy.

But wait, the answer is 10 instead of undefined.

In fact, the transformation process is correct, but one factor was overlooked: the passed-in parameter. After adding this factor, it can be seen as follows:

function test(v){

var v = 10 // 因為下面呼叫 test(10)

var v

console.log(v)

v = 3

}

test(10)At this point, you may still ask, “But didn’t I redeclare the variable before logging and not give it a value? Won’t it be overwritten as undefined?”

Let’s look at a simple example:

var v = 5

var v

console.log(v)The answer will be 5 instead of undefined. To understand this behavior, you can think back to splitting a sentence into two parts, declaration and assignment. If we split it like this and add hoisting, the above code can actually be imagined as follows:

var v

var v

v = 5

console.log(v)Now you know why the answer is 5.

At this point, you may feel like your head is about to explode. Why do you have to remember so many rules? Don’t worry, we have one last example that is guaranteed to make you scream.

console.log(a) //[Function: a]

var a

function a(){}In addition to variable declarations, function declarations will also be hoisted and have higher priority. Therefore, the above code will output function instead of undefined.

Okay, the basic concept of hoisting ends here. Let me summarize the key points for you:

- Both variable declarations and function declarations will be hoisted.

- Only declarations will be hoisted, not assignments.

- Don’t forget that there are parameters in functions.

Don’t worry, we haven’t talked about the new let and const added in ES6 yet.

Hoisting with let and const

In ES6, we have two new keywords for declaring variables, let and const. The behavior of these two keywords with hoisting is similar, so I will only use let as an example below. Take a look at the following code:

console.log(a) // ReferenceError: a is not defined

let aThank goodness, there are finally not so many rules to remember!

From the above code, it seems that let and const do not have variable hoisting, otherwise this error would not be thrown.

I used to think so naively, until I saw the following example:

var a = 10

function test(){

console.log(a)

let a

}

test()If let really doesn’t have hoisting, the answer should output 10, because the log line will access the variable var a = 10 outside. But!!!

The answer is: ReferenceError: a is not defined.

This means that it did hoist, but the behavior after hoisting is different from var, so at first glance, you might think it didn’t hoist.

We will explain this concept in detail later, but before that, let’s make a simple summary.

There are many articles that mention hoisting, and they mostly talk about the behavior of hoisting and the differences between let and const. But I think it’s a pity to only talk about it to this extent.

Because if you only understand to this extent, you will think that hoisting is just a bunch of complicated rules to remember, and it’s not a big deal. Who can remember so many rules? It’s just memorization, right?

This is because the above only lets you understand the “surface” and gives a few different examples to tell you that such behavior will occur, but it does not tell you “why it will happen” or “how it actually works”. If you really want to understand what hoisting is, you must find the answers to the following two questions. Once you find them, I guarantee that your two main veins will be unblocked:

- Why do we need hoisting?

- How does hoisting actually work?

Why do we need hoisting?

When asking such a question, you can think of it the other way around: “What if we don’t have hoisting?”

First, we must declare variables before we can use them.

This is actually a good practice.

Secondly, we must declare the function before we can use it.

This is not very convenient, as we may have to put the function declaration at the top of each file to ensure that the code below can call these functions.

Thirdly, it is impossible to achieve mutual function calls.

For example:

(omittedCodeBlock-7b50ff) We call logEvenOrOdd inside the loop, and we also call loop inside logEvenOrOdd. If we don’t have hoisting, the above code cannot be achieved because you cannot simultaneously achieve A on top of B while B is on top of A.

So why do we need hoisting? It is to solve the above problem.

To add to the correctness of this statement, I quote an article for everyone to read. In Note 4. Two words about “hoisting”. the author mentioned that he raised the topic on Twitter and mentioned mutual recursion as one of the reasons for hoisting. Brendan Eich also acknowledged that FDs hoisting is “for mutual recursion & generally to avoid painful bottom-up ML-like order”.

If you want to see the complete conversation screenshot, you can read this article: JavaScript series: variable hoisting and function hoisting, which is attached at the bottom.

How does hoisting work?

Now that we know what hoisting is and why we need it, the last missing piece of the puzzle is how hoisting works.

The best way to answer this question is to look at the ECMAScript specification. Just like when you want to study type conversion problems today, the solution is to look at the specification. The reason is simple because those rules are clearly written on it.

ECMAScript has many versions, and the later versions have more specifications. Therefore, for convenience, we use ES3 as an example below.

If you have read the rules of ES3, you will find that you cannot find anything related to hoisting as a keyword, and the paragraph related to this phenomenon is actually in Chapter 10: Execution Contexts.

Here is a very brief introduction to what Execution Contexts (EC) are. Whenever you enter a function, an EC is generated, which stores some information related to this function and puts this EC into the stack. When the function is executed, the EC is popped out.

The schematic diagram is roughly like this, remember that in addition to the EC of the function, there is also a global EC:

(Source: https://medium.freecodecamp.org/lets-learn-javascript-closures-66feb44f6a44)

In short, all the information needed by the function will exist in the EC, which is the execution environment. You can get everything you need from there.

ECMAScript describes it as follows:

When control is transferred to ECMAScript executable code, control is entering an execution context. Active execution contexts logically form a stack. The top execution context on this logical stack is the running execution context.

The key point is in 10.1.3 Variable Instantiation:

Every execution context has associated with it a variable object. Variables and functions declared in the source text are added as properties of the variable object. For function code, parameters are added as properties of the variable object.

Each EC has a corresponding variable object (VO for short), in which the variables and functions declared will be added to the VO. If it is a function, the parameters will also be added to the VO.

First, you can think of VO as just a JavaScript object.

Next, when will VO be used? You will use it when accessing values. For example, in the statement var a = 10, it can be divided into two parts:

var a: add a property called “a” to VO (if there is no property called “a”) and initialize it to undefined.a = 10: find the property called “a” in VO and set it to 10.

(What if it cannot find the property in VO? It will continuously search through the scope chain. If it cannot find it in any layer, an error will be thrown. Although the process of searching and creating the scope chain is related to this article, it is too much to explain. It is better to write another article separately, so I won’t mention it here.)

Next, let’s look at the next paragraph:

Which object is used as the variable object and what attributes are used for the properties depends on the type of code, but the remainder of the behaviour is generic. On entering an execution context, the properties are bound to the variable object in the following order:

The most essential sentence is “On entering an execution context, the properties are bound to the variable object in the following order”. When entering an EC, things will be put into VO in the following order:

The next paragraph is a bit long, so I’ll quote part of it:

For function code: for each formal parameter, as defined in the FormalParameterList, create a property of the variable object whose name is the Identifier and whose attributes are determined by the type of code. The values of the parameters are supplied by the caller as arguments to [[Call]].

If the caller supplies fewer parameter values than there are formal parameters, the extra formal parameters have value undefined.

In short, for parameters, they will be directly added to VO. If some parameters do not have values, their values will be initialized to undefined.

For example, if my function looks like this:

function test(a, b, c) {}

test(10)Then my VO will look like this:

{

a: 10,

b: undefined,

c: undefined

}So parameters are the first priority, and then we look at the second one:

For each FunctionDeclaration in the code, in source text order, create a property of the variable object whose name is the Identifier in the FunctionDeclaration, whose value is the result returned by creating a Function object as described in 13, and whose attributes are determined by the type of code.

If the variable object already has a property with this name, replace its value and attributes. Semantically, this step must follow the creation of FormalParameterList properties.

For function declarations, a property will also be added to VO. As for the value, it is the result returned after creating the function (you can think of it as a pointer to the function).

Next is the key point: “If there is already an attribute with the same name in VO, overwrite it.” Here’s a small example:

function test(a){

function a(){}

}

test(1)The VO will look like this, and the original parameter a is overwritten:

{

a: function a

}Now let’s take a look at how variable declarations should be handled:

For each VariableDeclaration or VariableDeclarationNoIn in the code, create a property of the variable object whose name is the Identifier in the VariableDeclaration or VariableDeclarationNoIn, whose value is undefined and whose attributes are determined by the type of code. If there is already a property of the variable object with the name of a declared variable, the value of the property and its attributes are not changed.

Semantically, this step must follow the creation of the FormalParameterList and FunctionDeclaration properties. In particular, if a declared variable has the same name as a declared function or formal parameter, the variable declaration does not disturb the existing property.

For variables, a new property is added to the VO with a value of undefined, and here’s the key point: “If the VO already has this property, the value will not be changed.”

To summarize, when we enter an EC (you can think of it as executing a function, but before running the code inside the function), we do the following three things in order:

- Put the parameters in the VO and set the values. Whatever is passed in is what it is, and if there is no value, it is set to undefined.

- Put the function declaration in the VO, overwriting it if there is already one with the same name.

- Put the variable declaration in the VO, ignoring it if there is already one with the same name.

After reading and understanding the specification, you can use this theory to explain the code we saw earlier:

function test(v){

console.log(v)

var v = 3

}

test(10)You can think of each function as having two stages of execution. The first stage is entering the EC, and the second stage is actually executing the code line by line.

When entering the EC, the VO is created. Since there are parameters passed in, v is put into the VO and its value is set to 10. Next, for the variable declaration inside, the VO already has the property v, so it is ignored. Therefore, the VO looks like this:

{

v: 10

}After the VO is created, the code is executed line by line. This is why the second log prints 10, because at that time, the value of v in the VO was indeed 10.

If you change the code to this:

function test(v){

console.log(v)

var v = 3

console.log(v)

}

test(10)Then the second log will print 3, because after executing the third line, the value in the VO is changed to 3.

The above is the execution process mentioned in the ES3 specification. If you remember this execution process, you don’t have to be afraid of any hoisting-related questions. Just follow the method in the specification to run it correctly.

After understanding this execution process, my first feeling was that everything became clear, and hoisting was no longer a mysterious thing. You just need to pretend that you are a JS engine and follow the process. My second feeling was, how does JS achieve this?

Compilation and Interpretation: How does the JS engine work?

Do you remember when I mentioned earlier that when I was learning programming, there was always a concept that “interpretation” meant that the program was executed line by line, and as a language that was interpreted, shouldn’t JS also be executed line by line?

But if it really runs line by line, how can it achieve the hoisting function? It’s impossible to know what line n + 1 is when you execute line n, so it’s impossible to hoist.

I searched the internet for a long time for an answer to this question, and finally found an article that I think is quite reasonable: Virtual Machine Talk (1): Interpreter, Tree Traversal Interpreter, Stack-Based and Register-Based, Hodgepodge.

There are a few points mentioned in the article that I think are very well written and have dispelled many of my previous misconceptions:

First, languages generally only define abstract semantics and do not enforce a specific implementation method. For example, we say that C is a compiled language, but C also has an interpreter. So when we say that a certain programming language is interpreted or compiled, we are actually referring to “most” rather than all.

In other words, when we say that JavaScript is an interpreted language, it does not mean that JavaScript cannot have a compiler, and vice versa.

Second, the biggest difference between an interpreter and a compiler is “execution”.

The compilation step is simply to compile the source code A into the target code B, but you need to ensure that the results of executing A and B are the same.

Interpretation is when you input the source code A, and the output is directly the semantics that you want to execute in your code. How it is done inside is a black box.

There is a good picture in the original article:

So there can also be compilation inside an interpreter, and this is not conflicting. Or you can write a super simple interpreter that compiles your source code and then executes it.

In fact, many types of interpreters operate by first compiling the source code into some intermediate code before executing it, so the compilation step is still very common, and JS also works this way.

When you abandon the old concept of “JS must be executed line by line” and embrace the idea that “actually mainstream JS engines have a compilation step”, you will not think that hoisting is an impossible thing to achieve.

As we have seen in the specification, we know the operating mode in ES3 and know about VO, but what the specification describes is only abstract, and it does not say where the processing is actually done, and this place is actually the compilation phase.

Speaking of the issue of compilation and interpretation, I have been stuck for a long time because there are many incorrect concepts in the past. Now I am slowly correcting them, and for hoisting, I actually had some confusion before about the difference between the specification and the implementation. Later, I even went to ask the author of You-Dont-Know-JS and was lucky enough to get a reply. Interested people can take a look: https://github.com/getify/You-Dont-Know-JS/issues/1375.

Operation of JS engine

As I mentioned above, mainstream JS engines now have a compilation phase, and hoisting is actually processed during this phase. With the introduction of the compilation phase, JS can be divided into two steps: compilation phase and execution phase.

During the compilation phase, all variable and function declarations are processed and added to the scope, and they can be used during execution. This article explains it very well: Hoisting in JavaScript, and I will just modify the code inside as an example.

For example, I have this piece of code:

var foo = "bar"

var a = 1

function bar() {

foo = "inside bar"

var a = 2

c = 3

console.log(c)

console.log(d)

}

bar()During the compilation phase, the declaration part is processed, so it will be like this:

Line 1:global scope,我要宣告一個變數叫做 foo

Line 2:global scope,我要宣告一個變數叫做 a

Line 3:global scope,我要宣告一個函式叫做 bar

Line 4:沒有任何變數宣告,不做事

Line 5:bar scope,我要宣告一個變數叫做 a

Line 6:沒有任何變數宣告,不做事

Line 7:沒有任何變數宣告,不做事

Line 8:沒有任何變數宣告,不做事After processing, it looks like this:

globalScope: {

foo: undefined,

a: undefined,

bar: function

}

barScope: {

a: undefined

}Next, enter the execution phase. There are two proprietary terms to remember before introducing them. It is better to understand them with an example:

var a = 10

console.log(a)There is a difference between these two lines. When we write the first line, we only need to know “where is the memory location of a”, and we don’t care what its value is.

The second line is “we only care about its value, give me the value”, so even though both lines have a, you can see that what they want to do is different.

We call the a in the first line an LHS (Left hand side) reference, and the a in the second line an RHS (Right hand side) reference. The left and right here refer to the left and right sides relative to the equal sign, but this way of understanding is not precise enough, so it is better to remember it like this:

LHS: Please help me find the location of this variable because I want to assign a value to it.

RHS: Please help me find the value of this variable because I want to use this value.

With this concept, let’s take a look at the example code above step by step:

var foo = "bar"

var a = 1

function bar() {

foo = "inside bar"

var a = 2

c = 3

console.log(c)

console.log(d)

}

bar()Line 1: var foo = “bar”

JS engine: global scope, do I have an LHS reference to foo here?

Execution result: The scope says yes, so it successfully finds foo and assigns a value to it.

The global scope at this time:

{

foo: "bar",

a: undefined,

bar: function

}Line 2: var a = 1

JS Engine: Global scope, do I have an LHS reference to a? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Scope says yes, so it successfully finds a and assigns it a value.

The global scope at this point:

{

foo: "bar",

a: 1,

bar: function

}Line 10: bar()

JS Engine: Global scope, do I have an RHS reference to bar? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Scope says yes, so it successfully returns the value of bar and calls the function.

Line 4: foo = “inside bar”

JS Engine: Bar scope, do I have an LHS reference to foo? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Bar scope says no, so it goes to the previous global scope.

JS Engine: Global scope, do I have an LHS reference to foo? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Yes, so it successfully finds foo and assigns it a value.

The global scope at this point:

{

foo: "inside bar",

a: 1,

bar: function

}Line 5: var a = 2

JS Engine: Bar scope, do I have an LHS reference to a? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Bar scope says yes, so it successfully finds a and assigns it a value.

The bar scope at this point:

{

a: 2

}Line 6: c = 3

JS Engine: Bar scope, do I have an LHS reference to c? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Bar scope says no, so it goes to the previous global scope.

JS Engine: Global scope, do I have an LHS reference to c? Have you seen it?

Execution result: No.

At this point, there are several possible outcomes. If you are in strict mode (use strict), it will return a ReferenceError: c is not defined error. If you are not in strict mode, the global scope will add c and set it to 3. Here, we assume that we are not in strict mode.

The global scope at this point:

{

foo: "inside bar",

a: 1,

bar: function,

c: 3

}Line 7: console.log(c)

JS Engine: Bar scope, do I have an RHS reference to c? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Bar scope says no, so it goes to the previous global scope.

JS Engine: Global scope, do I have an RHS reference to c? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Yes, so it successfully returns the value of c and calls console.log.

Line 8: console.log(d)

JS Engine: Bar scope, do I have an RHS reference to d? Have you seen it?

Execution result: Bar scope says no, so it goes to the previous global scope.

JS Engine: Global scope, do I have an RHS reference to d? Have you seen it?

Execution result: No, so it returns an error ReferenceError: d is not defined.

The above is the working process of the JS engine. For more detailed information, please refer to: You Don’t Know JS: Scope & Closures, Chapter 4: Hoisting, Hoisting in JavaScript.

Summary

Let’s review the ten items we mentioned at the beginning:

- Do you know what hoisting is?

- Do you know that hoisting only hoists declarations, not assignments?

- Do you know the hoisting priority when function declarations, function parameters, and variable declarations appear together?

- Do you know that let and const do not have hoisting?

- Do you know that the fourth item is wrong and that they do have hoisting, but the form is different?

- Do you know that there is a concept called TDZ (Temporal Dead Zone) related to the fifth item?

- Have you read the ES3 specification and know how it is described?

- Have you read the ES6 specification and know how it is described?

- Do you know the principle behind hoisting?

- Have you seen the code compiled by V8?

We have covered all seven points in great detail, and what’s left is:

- You know about the concept of TDZ (Temporal Dead Zone) related to the sixth point.

- You have seen how it is described in the ES6 specification.

- You have seen the code compiled by V8.

I don’t plan to go into detail about the ES6 specification (and I haven’t read it in detail yet), because there are still many changes, but the basic principles remain the same. It’s just that there are some proprietary terms added. If you want to know more, you can refer to this classic article: ECMA-262-5 in detail. Chapter 3.2. Lexical environments: ECMAScript implementation..

We have already covered a lot of things related to hoisting, and all the mechanisms related to hoisting have been explained. However, I believe it will still take some time to absorb all of this. But I believe that after you have absorbed it, you will feel refreshed and realize that hoisting is not that complicated.

Next, we will move on to the last part of this article, which is TDZ and V8.

Temporal Dead Zone

Do you remember that we said let and const actually have hoisting? And we gave a small example to verify this.

Let and const do have hoisting. The difference between them and var is that after hoisting, the variable declared by var is initialized to undefined, while the declaration of let and const is not initialized to undefined. And if you try to access it before “assignment”, an error will be thrown.

During the “period” after hoisting and before “assignment”, if you try to access it, an error will be thrown. This period is called the TDZ, which is a term proposed to explain the hoisting behavior of let and const.

We use the following code as an example:

function test() {

var a = 1; // c 的 TDZ 開始

var b = 2;

console.log(c) // 錯誤

if (a > 1) {

console.log(a)

}

let c = 10 // c 的 TDZ 結束

}

test()If you try to access c before line 8 is executed, an error will be thrown. Note that TDZ is not a spatial concept, but a temporal one. For example, in the following code:

function test() {

yo() // c 的 TDZ 開始

let c = 10 // c 的 TDZ 結束

function yo(){

console.log(c)

}

}

test()When you enter the test function, c is already in the TDZ, so when you execute yo and execute console.log(c), you are still in the TDZ, and you have to wait until let c = 10 is executed to end the TDZ.

So it’s not that putting console.log(c) below let c = 10 solves the problem, but that it needs to be executed later in the “execution order”.

Or you can ignore these terms and summarize it in one sentence:

Let and const also have hoisting, but they are not initialized to undefined, and an error will be thrown if you try to access them before assignment.

Byte code reading experience

Since we talked about the JS engine above, it would be a pity not to talk about V8. When I was studying hoisting, I always wanted to know one thing: what does the code compiled by V8 look like?

Thanks to this wonderful article Understanding V8’s Bytecode, we can try to compile the code into byte code using node.js and try to interpret it.

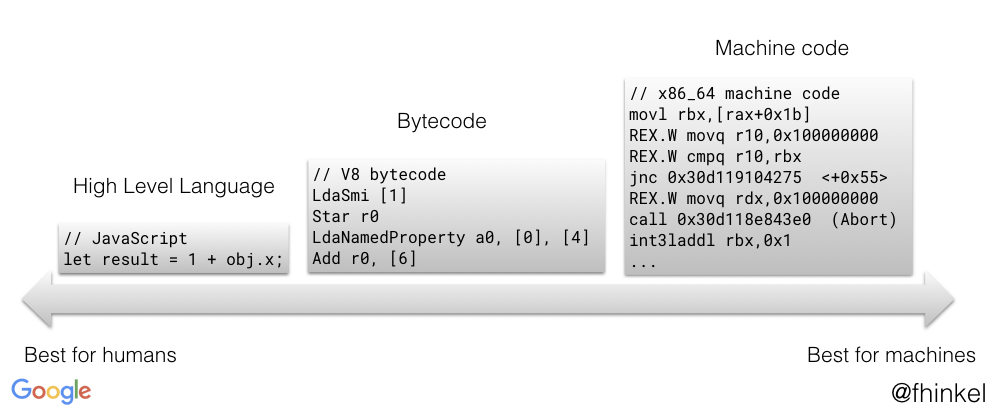

Before we start, let’s introduce what byte code is. It is a language between high-level languages and machine code. It is not as easy to understand as high-level languages, but it is much easier to understand than machine code, and it is more efficient to execute.

The following figure explains the relationship between them very clearly:

Next, we use this simple function as an example to see what it looks like after compilation:

function funcA() {

var a = 10

console.log(a)

}

funcA()Although there is only one function, there will still be a lot of things when running with node.js, so we put the result into a file first: node --print-bytecode test.js > byte_code.txt

The compiled result looks like this:

[generating bytecode for function: funcA]

Parameter count 1

Frame size 24

76 E> 0xeefa4feb062 @ 0 : 91 StackCheck

93 S> 0xeefa4feb063 @ 1 : 03 0a LdaSmi [10]

0xeefa4feb065 @ 3 : 1e fb Star r0

100 S> 0xeefa4feb067 @ 5 : 0a 00 02 LdaGlobal [0], [2]

0xeefa4feb06a @ 8 : 1e f9 Star r2

108 E> 0xeefa4feb06c @ 10 : 20 f9 01 04 LdaNamedProperty r2, [1], [4]

0xeefa4feb070 @ 14 : 1e fa Star r1

108 E> 0xeefa4feb072 @ 16 : 4c fa f9 fb 00 CallProperty1 r1, r2, r0, [0]

0xeefa4feb077 @ 21 : 04 LdaUndefined

115 S> 0xeefa4feb078 @ 22 : 95 Return

Constant pool (size = 2)

Handler Table (size = 16)We clear some of the information at the beginning and add comments to let you know what the above code means (I don’t really understand it, and there seems to be little information on this aspect. Please correct me if I’m wrong):

StackCheck

LdaSmi [10] // 把 10 放到 accumulator 裡面

Star r0 // 把 accumulator 的值放到 r0 裡,所以 r0 = 10

LdaGlobal [0], [2] // 載入一個 Global 的東西到 acc 裡

Star r2 // 把它存到 r2,根據後見之明,r2 應該就是 console

LdaNamedProperty r2, [1], [4] // 載入一個 r2 的 Property(應該就是 log)

Star r1 // 把它存到 r1,也就是 r1 = console.log

CallProperty1 r1, r2, r0, [0] // console.log.call(console, 10)

LdaUndefined // 把 undefined 放到 acc

Return // return undefinedThen we reverse the order to look like this:

function funcA() {

console.log(a)

var a = 10

}

funcA()Let’s take a look at what the output byte code looks like. Before explaining, you can compare it with the previous one to see the difference:

StackCheck

LdaGlobal [0], [2] // 載入一個 Global 的東西到 acc 裡

Star r2 // 把它存到 r2,根據後見之明,r2 應該就是 console

LdaNamedProperty r2, [1], [4] // 載入一個 r2 的 Property(應該就是 log)

Star r1 // 把它存到 r1,也就是 r1 = console.log

CallProperty1 r1, r2, r0, [0] // console.log.call(console, undefined)

LdaSmi [10] // 把 10 放到 accumulator 裡面

Star r0 // 把 accumulator 的值放到 r0 裡,所以 r0 = 10

LdaUndefined // 把 undefined 放到 acc

Return // return undefined Actually, the only difference is that the order has been changed, and r0 is directly logged in the output. I’m not sure if r0 was originally undefined or if it was initialized as undefined elsewhere.

Next, let’s see what happens if we try to print an undeclared variable:

function funcA() {

console.log(b)

var a = 10

}

funcA()Because most of the code is duplicated from before, I won’t comment on it again:

StackCheck

LdaGlobal [0], [2]

Star r2

LdaNamedProperty r2, [1], [4]

Star r1

LdaGlobal [2], [6] // 試圖載入 b 的值,出錯

Star r3

CallProperty1 r1, r2, r3, [0]

LdaSmi [10]

Star r0

LdaUndefined

Return The key point of the whole paragraph is only the line LdaGlobal, which seems to be loading the value of b. It should be this line that causes the error during execution because b cannot be found in the global scope.

After reading the basics, let’s see what let is compiled into:

function funcA() {

console.log(a)

let a = 10

}

funcA()The compiled result:

LdaTheHole // 把 hole 載入到 acc 去

Star r0 // r0 = hole

StackCheck

LdaGlobal [0], [2]

Star r2 // r2 = console

LdaNamedProperty r2, [1], [4]

Star r1 // r1 = console.log

Ldar r0 // 載入 r0

ThrowReferenceErrorIfHole [2] // 拋出錯誤

CallProperty1 r1, r2, r0, [0] // console.log.call(console, r0)

LdaSmi [10]

Star r0

LdaUndefined

ReturnYou will see a mysterious thing called a hole, which is actually what we call the TDZ. That’s why there is a line ThrowReferenceErrorIfHole, which means that if we try to access the value of this hole before the TDZ ends, an error will be thrown.

So far, we have explained how the TDZ actually works during the compilation phase, using this special thing called a hole.

Conclusion

Recently, I have been trying to fill in some of my basic knowledge of JavaScript. If I hadn’t read two articles, 解读ECMAScript[1]——执行环境、作用域及闭包 and JS 作用域, I probably wouldn’t have written this article.

Several points that are frequently tested in JavaScript are well-known: this, prototype, closure, and hoisting. These seemingly unrelated things can be somewhat connected if you can understand the underlying operating model of JavaScript, forming a complete theory.

I also mentioned in the article that the process of explaining the execution environment can be supplemented to explain closures. You will find that many things can actually be integrated. If I have the opportunity in the future, I will turn this into a series and break down those concepts in JavaScript that you think are difficult but actually aren’t.

Before writing this article, I had been brewing it for about a month, constantly looking for information, digesting it, and transforming it into my own understanding. I am also very grateful to the author of the JS scope article and the author of YDKJS for patiently answering my questions.

Finally, I hope this article is helpful to you. If there are any errors, please let me know. Thank you.

References:

- MDN: Hoisting

- ECMA-262-3 in detail. Chapter 2. Variable object.

- JS 作用域

- JavaScript Optimization Patterns (Part 2)

- danbev/learning-v8

- Why is there a “temporal dead zone” in ES6?

- exploringjs: Variables and scoping #

- 由阮一峰老师的一条微博引发的 TDZ 思考

- 理解ES6中的暂时死区(TDZ)

- TEMPORAL DEAD ZONE (TDZ) DEMYSTIFIED

- MDN: let

- Grokking V8 closures for fun (and profit?)

- 解读ECMAScript[1]——执行环境、作用域及闭包

Comments