How many data types are there in JavaScript? And what are they?

Before discussing data types, we should first know how many types there are in JavaScript and have a basic understanding of each type. Before we start, you can count them yourself and then compare your answer with mine to see if it is correct.

As JavaScript evolves, this article will use the latest ECMAScript 2021 as the standard. If “spec” is mentioned below, it refers to the ECMAScript 2021 language specification .

How many types are there in JavaScript?

In the spec, in the sixth chapter: “ECMAScript Data Types and Values”, it talks about types and divides them into two types:

Types are further subclassified into ECMAScript language types and specification types. (p.71)

What are ECMAScript language types and what are specification types? Let’s start with the latter:

A specification type corresponds to meta-values that are used within algorithms to describe the semantics of ECMAScript language constructs and ECMAScript language types. The specification types include Reference, List, Completion, Property Descriptor, Environment Record, Abstract Closure, and Data Block. (p.100)

Specification types are named after their use in the specification and can be used to describe some syntax or algorithms in the specification. For example, you will see types such as “Reference”, “List”, and “Environment Record” in the specification.

The other type, ECMAScript language types, is described in the specification as follows:

An ECMAScript language type corresponds to values that are directly manipulated by an ECMAScript programmer using the ECMAScript language. (p.71)

Therefore, this is the type we generally talk about in JavaScript and the topic we want to discuss in this article.

So how many types are there? According to the specification:

The ECMAScript language types are Undefined, Null, Boolean, String, Symbol, Number, BigInt, and Object. (p.71)

So there are 8 types, namely:

- Undefined

- Null

- Boolean

- String

- Symbol

- Number

- BigInt

- Object

Some people may count 7 types, excluding the latest BigInt, and some may count 6 types, excluding the Symbol added in ES6. But in any case, the answer is 8 types.

Next, let’s briefly look at how the specification describes these eight types and their basic usage.

1. Undefined

The specification describes it as follows:

The Undefined type has exactly one value, called undefined. Any variable that has not been assigned a value has the value undefined. (p.72)

Therefore, Undefined is a type, and undefined is a value of the Undefined type, just like “Number is a type, and 9 is a value of the Number type.”.

The Undefined type has only one value, undefined. When a variable is not assigned any value, its value is undefined.

This is easy to verify:

var a

console.log(a) // undefinedUsing typeof also yields the result 'undefined':

var a

if (typeof a === 'undefined') { // 注意,typeof 的回傳值是字串

console.log('hello') // hello

}2. Null

The specification describes it more simply:

The Null type has exactly one value, called null. (p.72)

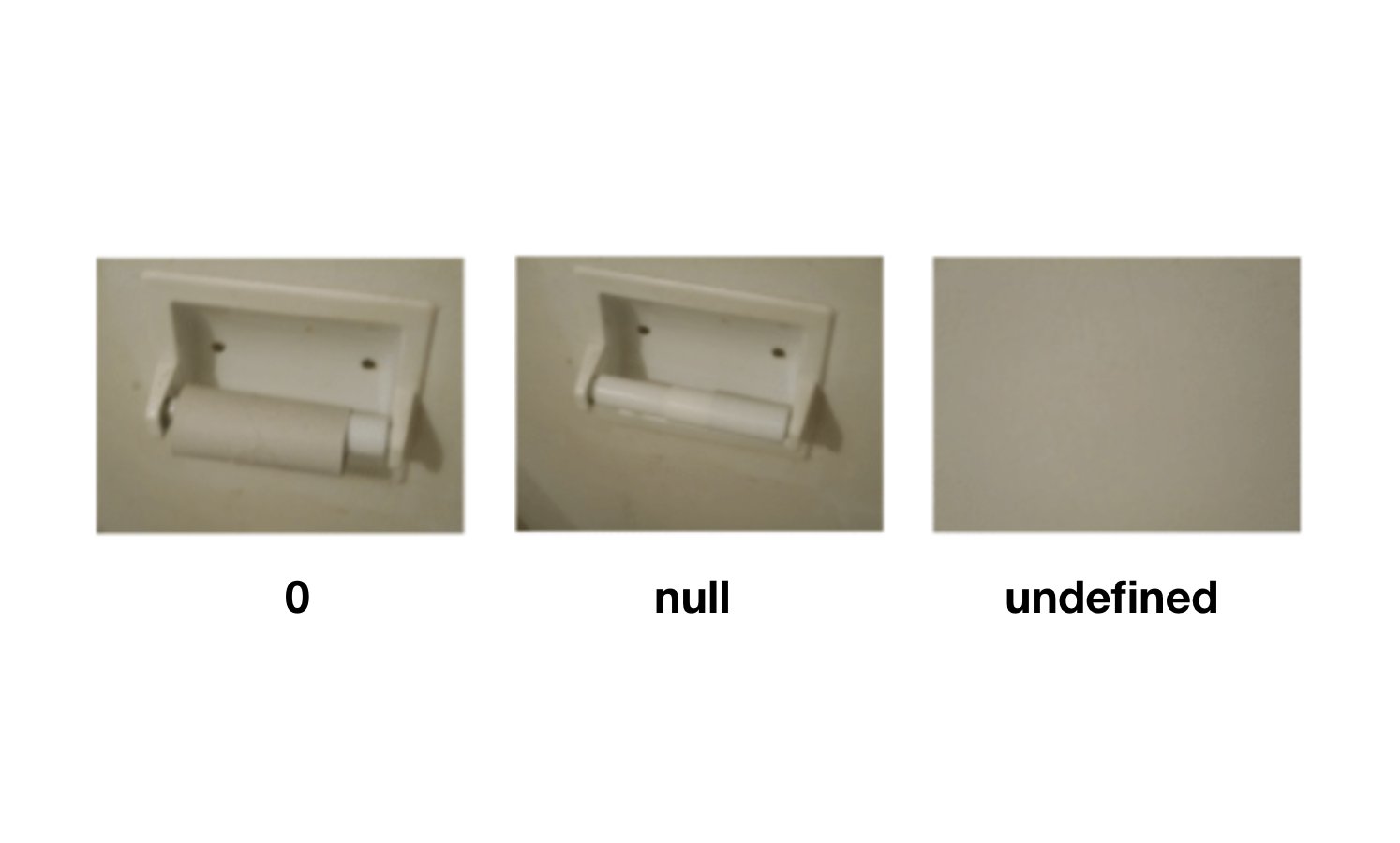

Some people may not be able to distinguish between null and undefined, because these two are indeed somewhat similar. At this time, let’s take a look at a classic meme (source: Twitter @ddprrt):

undefined basically means non-existent, while null means “exists but there is nothing”, giving a feeling of deliberately using null to mark “nothing”.

Also, there is one thing to note, that if you use typeof, you will get the wrong result 'object':

console.log(typeof null) // 'object'This is one of the most famous bugs in JavaScript. In this article: The history of “typeof null”, the author explains why this bug exists and provides actual early JavaScript engine code to support it. JavaScript creator Brendan Eich also left a comment below, correcting some details.

3. Boolean

The specification describes it as:

The Boolean type represents a logical entity having two values, called true and false. (p.72)

So the value of the Boolean type is either true or false, which everyone should be familiar with, so I won’t go into it.

4. String

The description of String in the specification is relatively long, and we excerpt a section to see:

The String type is the set of all ordered sequences of zero or more 16-bit unsigned integer values (“elements”) up to a

maximum length of 2^53 - 1 elements. The String type is generally used to represent textual data in a running ECMAScript program, in which case each element in the String is treated as a UTF-16 code unit value (p.72)

Above it says that a string is a sequence of 16-bit numbers, and these numbers are UTF-16 code units. The maximum length of a string is 2^53 - 1.

I believe that many people may still not understand what this means after reading it. There are many things that can be said about UTF-16 and string encoding. I will write another article on this later. For now, we just need to roughly understand the definition of a string.

5. Symbol

Next, let’s take a look at Symbol:

The Symbol type is the set of all non-String values that may be used as the key of an Object property.

Each possible Symbol value is unique and immutable.

Each Symbol value immutably holds an associated value called [[Description]] that is either undefined or a String value. (p.73)

Symbol is a data type added in ES6. As mentioned above, it is the only thing other than a string that can be used as a key for an object. Each Symbol value is unique.

Let’s look at an example:

var s1 = Symbol()

var s2 = Symbol('test') // 可以幫 Symbol 加上敘述以供辨識

var s3 = Symbol('test')

console.log(s2 === s3) // false,Symbol 是獨一無二的

console.log(s2.description) // test 用這個可以取得敘述

var obj = {}

obj[s2] = 'hello' // 可以當成 key 使用

console.log(obj[s2]) // helloIn short, Symbol is basically used as a key for objects. Because of its unique characteristics, it will not conflict with other keys.

However, if you want, you can still use Symbol.for() to get the same Symbol, like this:

var s1 = Symbol.for('a')

var s2 = Symbol.for('a')

console.log(s1 === s2) // trueWhy is this possible? When you use the Symbol.for function, it first searches a global Symbol registry to see if the Symbol exists. If it does, it returns it. If not, it creates a new one and writes it to the Symbol registry. Therefore, it doesn’t actually generate the same Symbol, it just helps you find the Symbol that was previously created.

In addition, there is an important feature of hiding information. When you use for in, if the key is of type Symbol, it will not be listed:

var obj = {

a: 1,

[Symbol.for('hello')]: 2

}

for(let key in obj) {

console.log(key) // a

}Knowing these features of Symbol, you may be curious like me, where can Symbol actually be used and how should it be used?

To find the answer to this question, let’s look at a classic practical example: React.

If you have used React, you should be familiar with this syntax:

function App() {

return (

<div>hello</div>

)

}This syntax that mixes JavaScript and HTML is called JSX, and behind it is a Babel plugin that converts the above code to the following:

function App() {

return (

React.createElement(

'div', // 標籤

null, // props

'hello' // children

)

)

}And React.createElement returns an object like this, which is what we usually call the Virtual DOM:

{

type: 'div',

props: {

children: 'hello'

},

key: null,

ref: null,

_isReactElement: true

}So in the end, it’s all JavaScript, nothing special, and React has basic protection against XSS, so unless you use the dangerouslySetInnerHTML attribute (which is intentionally designed to be so long), you cannot insert HTML, for example:

function App({ text }) {

return (

<div>{text}</div>

)

}

const text = "<h1>hello</h1>"

ReactDOM.render(

<App text={text} />,

document.body

)The text you pass in will be placed on the DOM using textContent, so only the plain text <h1>hello</h1> will appear, not in the form of HTML tags.

Okay, these all look fine, but what if the text in the example above is not text, but an object? For example:

function App({ text }) {

return (

<div>{text}</div>

)

}

const text = {

type: 'div',

props: {

dangerouslySetInnerHTML: {

__html: '<svg onload="alert(1)">'

}

},

key: null,

ref: null,

_isReactElement: true

}

ReactDOM.render(

<App text={text} />,

document.body

)Since React.createElement ultimately returns an object, we can directly convert text into the format that React.createElement returns, it will be treated as a React component, and then we can control its properties and use the dangerouslySetInnerHTML mentioned earlier to insert any value, thereby achieving XSS!

This was the vulnerability in React before v0.14. As long as the attacker can pass an object as a parameter and can control these properties, XSS can be achieved.

You can imagine a situation where a website has a feature to set a nickname. In the part where the nickname is displayed, the website will call an API to render a React component based on the response.data.nickname returned by the API. However, the server has a bug in setting the nickname. Although it should only be able to fill in strings, because there is no type checking, you can set the nickname to an object.

Therefore, if you set the nickname to an object, you can set it as a React component like the example above, and when rendering, it will trigger XSS.

What is the fix? It’s simple, just replace the original _isReactElement with Symbol:

const text = {

type: 'div',

props: {

children: 'hello'

},

key: null,

ref: null,

$$typeof: Symbol.for('react.element')

}Why does this work? Because according to the situation we imagined above, when I modify the nickname to an object, no matter what $$typeof is passed, it is not Symbol.for('react.element'), because that’s the nature of Symbol. I cannot generate this value from the server.

Unless I can control this object from JavaScript, but if I can control it from JavaScript, it usually means that I can execute any code (for example, I have found an XSS vulnerability).

In this way, React can prevent the attack method we mentioned above. Attackers cannot pretend to be a React component through an object from the server or elsewhere, because they cannot forge Symbol, which is an important part of Symbol in practical use.

Dan’s blog has an article about this, and the content above is also referenced from this blog: Why Do React Elements Have a $$typeof Property?

6. Number

The spec for Number is also very long, let’s take a look at it briefly:

The Number type has exactly 18,437,736,874,454,810,627 (that is, 2^64 - 2^53 + 3) values, representing the double-precision 64-bit format IEEE 754-2019 values as specified in the IEEE Standard for Binary Floating-Point Arithmetic, except that the 9,007,199,254,740,990 (that is, 2^53 - 2) distinct “Not-a-Number” values of the IEEE Standard are represented in ECMAScript as a single special NaN value. (p.76)

It mentions the possible values for the Number type, which has a specific number. This means that this type cannot store all numbers completely, and there will be errors once it exceeds a certain range.

Furthermore, the spec also states that the storage format is “double-precision 64-bit format IEEE 754-2019”, which clearly specifies the standard used for storage. This also shows that the numbers in JS are all 64-bit.

The range mentioned above is a very important part, which can be seen more clearly in the example below:

var a = 123456789123456789

var b = a + 1

console.log(a === b) // true

console.log(a) // 123456789123456780What! Why is the number still the same after adding one? And why is the printed value not the one we set initially? If you think about it carefully, you will find that it is very reasonable according to the storage mechanism of Number. As mentioned above, Number in JS is a 64-bit number, and 64 bits is a limited space, so the numbers that can be stored are also limited.

This is like the pigeonhole principle. If you have N cages and N+1 pigeons, and you put all the pigeons into the cages, there must be two pigeons in the same cage. The same goes for Number. The storage space is limited, and the numbers are infinite, so you cannot store all numbers accurately, and there will be errors.

Regarding other details, I will write another article specifically discussing numbers later.

7. BigInt

BigInt is a type added in ES2020, described as follows:

The BigInt type represents an integer value. The value may be any size and is not limited to a particular bit-width. (p.85)

As you can see, there is a very obvious difference between BigInt and Number. Theoretically, BigInt can store numbers without any upper limit. From this, we can roughly guess when to use BigInt and when to use Number.

If we rewrite the example of Number using BigInt, there will be no problem:

var a = 123456789123456789n // n 代表 BigInt

var b = a + 1n

console.log(a === b) // false

console.log(a) // 123456789123456789nThis is why we need BigInt. More details will be discussed in another article later.

8. Object

Finally, let’s take a look at our Object. I will excerpt some key points:

An Object is logically a collection of properties.

Properties are identified using key values. A property key value is either an ECMAScript String value or a Symbol value. All String and Symbol values, including the empty String, are valid as property keys. A property name is a property key that is a String value.

Property keys are used to access properties and their values(p.89)

An object is a collection of properties, and the “key value” mentioned in the second paragraph is actually the key we often talk about, used to obtain the value of a property. From the spec, we can also see some interesting things, such as the fact that the key of an object must be a string or a symbol. This means that if you use a number as a key, it is actually a string behind the scenes:

var obj = {

1: 'abc',

}

console.log(obj[1]) // abc

console.log(obj['1']) // abcAnd an empty string can also be used as a key, which is valid:

var obj = {

'': 123

}

console.log(obj['']) // 123Objects are a very important concept in JavaScript, so there will be several articles discussing object-related things later.

I believe everyone has heard of a saying that there are two types of data types in JavaScript: primitive data types and objects. Basically, all types except objects are primitive data types.

However, in the ECMAScript spec, the term “primitive data type” does not appear, only “primitive values” appear, for example:

A primitive value is a member of one of the following built-in types: Undefined, Null, Boolean, Number, BigInt, String, and Symbol; an object is a member of the built-in type Object; (p.49)

The term “primitive type” does appear, but only once:

If an object is capable of converting to more than one primitive type, it may use the optional hint preferredType to favour that type (p.112)

The term “primitive data type” appears most frequently on the Internet in Java, although it does not appear in the JavaScript spec, and “primitive data type” or “primitive type” is not formally defined (only primitive value is formally defined), but it seems reasonable to call the data type that represents primitive value as primitive data type.

Anyway, these are just some terms. I just want to supplement the text in the spec. When using it in daily life, I think it is okay to say primitive data type.

Summary

The following are the eight different data types mentioned in the current ECMAScript 2021 spec:

- Undefined

- Null

- Boolean

- String

- Symbol

- Number

- BigInt

- Object

I briefly introduced each type and some small knowledge seen from the spec, and made a more complete introduction to the Symbol type.

After reading these, I am curious about a question, that is, when will there be a ninth type? If so, what is most likely to be?

I checked the proposals of TC39 and found that there is currently only one proposal in stage 1 that may add a primitive data type, called BigDecimal, which is used to handle decimals, just like the naming in Java.

Although this proposal is still in the early stage, I think it is indeed possible to be adopted in the future. After all, JavaScript currently needs to handle decimals accurately, and it still relies on various third-party libraries, just like handling large numbers in the past. If there is native API support, it would be great, but there is still a long way to go.

Comments