Introduction

After acquiring knowledge, how can you determine whether it is correct or not? In the field of programming, this is actually a relatively simple question. You just need to check how the specification is written (if there is one).

For example, various language features of JavaScript can be found in the ECMAScript Specification. Why [] === [] is false, why 'b' + 'a' + + 'a' + 'a' is baNaNa, all of these are explained in detail in the specification, using what rules to perform the conversion.

In addition to JS, almost all HTML or other related specifications in the Web field can be found on w3.org or whatwg.org, and the resources are quite rich.

Although the implementation of browsers may be different from what is written in the specification (such as this article), the spec is the most complete and authoritative place, so it is correct to come here to find information.

If you search for the CORS spec, you may find RFC6454 - The Web Origin Concept and W3C’s Cross-Origin Resource Sharing, but these two have been replaced by a document called Fetch.

At first, I was puzzled and thought I had read it wrong. What is the relationship between fetch and CORS? Later, I learned that the fetch here is different from the fetch in the Web API. This specification defines everything related to “fetching data”, as written in its outline:

The Fetch standard defines requests, responses, and the process that binds them: fetching.

In this article, let’s take a look at the CORS-related specifications together, proving that what I said in the previous articles is not nonsense, but based on facts. Since the specification is quite long, I will only pick some key points that I think are important. If you want to understand all the content of the specification, you still need to read it yourself.

(The version of the specification referred to when this article was published is: Living Standard — Last Updated 15 February 2021. For the latest specification, please refer to: Fetch)

Let’s start with something simple

Specifications are very complete, so the content is extensive and messy. If you don’t start with something simple, it’s easy to get discouraged. The simplest part is the Goals and Preface at the beginning, which state:

The goal is to unify fetching across the web platform and provide consistent handling of everything that involves, including:

- URL schemes

- Redirects

- Cross-origin semantics

- CSP

- Service workers

- Mixed Content

RefererTo do so it also supersedes the HTTP

Originheader semantics originally defined in The Web Origin Concept

This specification integrates everything related to “fetching”, including what we are most concerned about, CORS or other related operations. It also mentions that this specification supersedes the original RFC6454 - The Web Origin Concept.

Then, the preface states:

At a high level, fetching a resource is a fairly simple operation. A request goes in, a response comes out. The details of that operation are however quite involved and used to not be written down carefully and differ from one API to the next.

Fetching data may seem simple, just send a request and receive a response, but in reality, it is quite complex. The lack of a standardized specification has led to inconsistent implementations of each API. This is why the Fetch Standard was created, to provide a unified architecture for fetching resources, such as images, scripts, and CSS, and to manage these behaviors.

The Fetch Standard also defines the fetch() JavaScript API, which exposes most of the networking functionality at a low level of abstraction.

The definition of Origin is provided in section 3.1 of the Origin header, which includes an ABNF rule. The content of Origin can only be one of two types: "null" or a combination of scheme, host, and port.

It is important to note the difference between the new and old specifications. In the old specification, Origin could be a list, but in the new specification, it is limited to one. In any case, the definition of Origin is a combination of scheme, host, and port.

Moving on to CORS, it is introduced in section 3.2 of the CORS protocol. The introduction is crucial, as the CORS protocol exists to allow sharing responses cross-origin and to enable more versatile fetches than possible with HTML’s form element. It is layered on top of HTTP and allows responses to declare that they can be shared with other origins.

The CORS protocol needs to be an opt-in mechanism to prevent data leakage from responses behind a firewall (intranets). Additionally, for requests including credentials, it needs to be opt-in to prevent the leakage of potentially sensitive data.

Next, the following paragraph in section 3.2.1 General is also important:

The CORS protocol consists of a set of headers that indicates whether a response can be shared cross-origin.

For requests that are more involved than what is possible with HTML’s form element, a CORS-preflight request is performed, to ensure request’s current URL supports the CORS protocol.

There are two key points mentioned here. The first is that CORS determines whether a response can be shared cross-origin through headers. This is what I mentioned in the previous article:

In short, CORS uses a set of response headers to tell the browser which resources the front-end has permission to access.

The second point is that if a request is more complex than what can be expressed with an HTML form element, a CORS-preflight request will be made.

So what does it mean to be “more complex than what can be expressed with an HTML form element”? We’ll look at that later, but first let’s look at these two sections:

3.2.2. HTTP requests

A CORS request is an HTTP request that includes an

Originheader. It cannot be reliably identified as participating in the CORS protocol as theOriginheader is also included for all requests whose method is neitherGETnorHEAD.

This is quite special. If I understand correctly, it means that an HTTP request is called a CORS request if it contains the Origin header. However, this does not mean that the request is related to the CORS protocol, as the Origin header is also included for all requests whose method is neither GET nor HEAD.

To verify this behavior, I created a simple form:

<form action="/test" method="POST">

<input name="a" />

<input type="submit" />

</form>Then I tried both POST and GET methods, and found that this is indeed the case. The GET request did not include the Origin header, but the POST request did. So according to the specification, submitting data with a form POST to the same origin is also called a CORS request. Strange knowledge has increased again.

A CORS-preflight request is a CORS request that checks to see if the CORS protocol is understood. It uses

OPTIONSas method and includes these headers:

Access-Control-Request-Method

Indicates which method a future CORS request to the same resource might use.

Access-Control-Request-Headers

Indicates which headers a future CORS request to the same resource might use.

A CORS-preflight request uses OPTIONS as the method to check whether the server understands the CORS protocol.

One thing to note here is that, as stated on MDN:

Some requests do not trigger a CORS preflight. These are called “simple requests” in this article, although the Fetch standard (which defines CORS) does not use this term.

The Fetch specification does not use the term “simple request” to distinguish whether a request will trigger a CORS-preflight request.

The preflight request in the CORS protocol includes these two headers:

- Access-Control-Request-Method

- Access-Control-Request-Headers

to indicate the method and headers that may be used in the subsequent CORS request, as we mentioned in the previous article.

Moving on to the section about responses:

3.2.3. HTTP responses

An HTTP response to a CORS request can include the following headers:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin

Indicates whether the response can be shared, via returning the literal value of theOriginrequest header (which can benull) or*in a response.

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials

Indicates whether the response can be shared when request’s credentials mode is “include”.

These two headers are for CORS requests and were already mentioned in the previous article. The former is used to determine which origins are allowed, while the latter determines whether cookies can be sent and received.

An HTTP response to a CORS-preflight request can include the following headers:

Access-Control-Allow-Methods

Indicates which methods are supported by the response’s URL for the purposes of the CORS protocol.

Access-Control-Allow-Headers

Indicates which headers are supported by the response’s URL for the purposes of the CORS protocol.

Access-Control-Max-Age

Indicates the number of seconds (5 by default) the information provided by theAccess-Control-Allow-MethodsandAccess-Control-Allow-Headersheaders can be cached.

CORS-preflight requests are a type of CORS request, so the response headers mentioned above for CORS requests can also be used for CORS-preflight requests. In addition, three more headers are defined:

- Access-Control-Allow-Methods: which methods can be used

- Access-Control-Allow-Headers: which headers can be used

- Access-Control-Max-Age: how long the first two headers can be cached

It’s worth noting the third header, which has a default value of 5 seconds. This means that CORS response headers for the same resource can be reused within 5 seconds.

An HTTP response to a CORS request that is not a CORS-preflight request can also include the following header:

Access-Control-Expose-Headers

Indicates which headers can be exposed as part of the response by listing their names.

For non-preflight CORS requests, the Access-Control-Expose-Headers header can be provided to specify which headers can be accessed. If not specified, even if the response is obtained, the header cannot be accessed.

Now let’s go back to the question mentioned earlier: “What triggers a preflight request?”

Preflight request

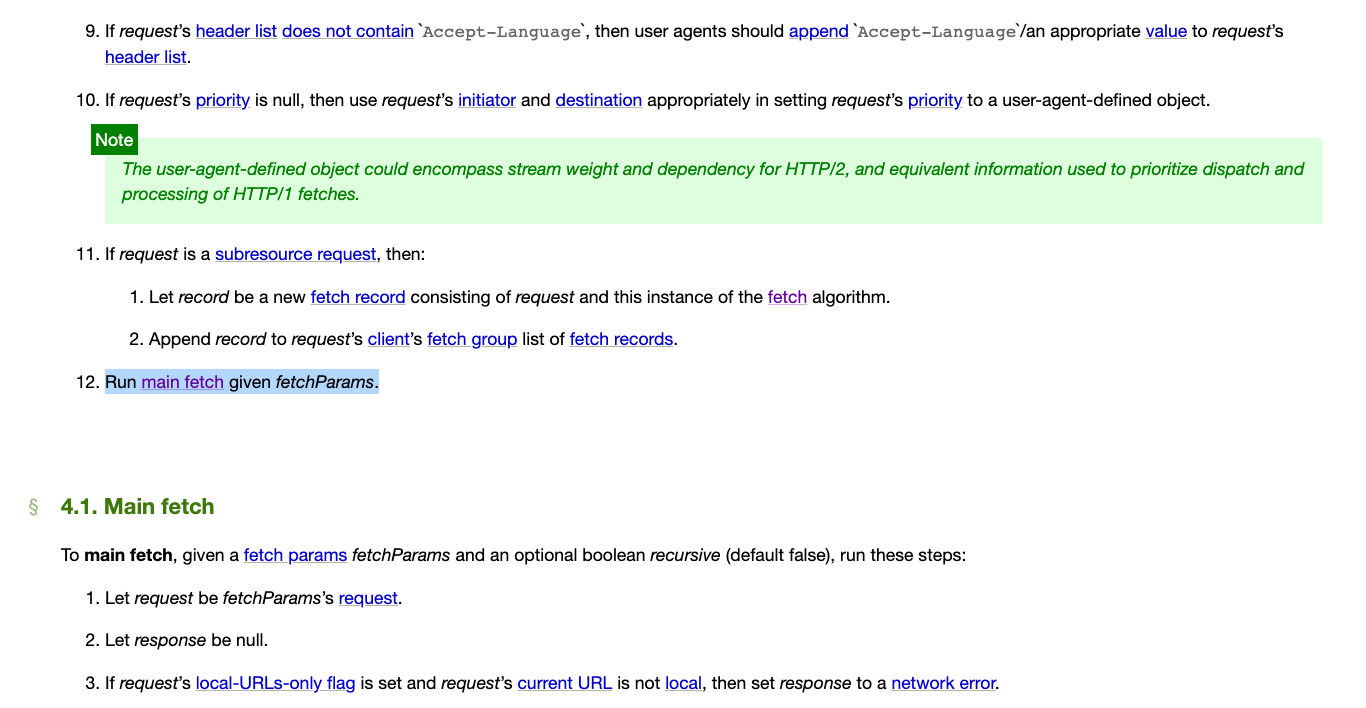

The rules for fetching resources are described in detail in section 4.1. Main fetch. We are interested in point 5:

request’s use-CORS-preflight flag is set

request’s unsafe-request flag is set and either request’s method is not a CORS-safelisted method or CORS-unsafe request-header names with request’s header list is not empty

- Set request’s response tainting to “cors”.

- Let corsWithPreflightResponse be the result of performing an HTTP fetch using request with the CORS-preflight flag set.

- If corsWithPreflightResponse is a network error, then clear cache entries using request.

- Return corsWithPreflightResponse.

If the method of the request is not a CORS-safelisted method or if the header contains CORS-unsafe request-header names, the CORS-preflight flag will be set and an HTTP fetch will be performed.

Continuing down the line, in the HTTP fetch process, it will be determined whether this flag has been set, and if so, a CORS-preflight fetch will be performed.

All of the above can be found in the spec:

2.2.1 Methods

A CORS-safelisted method is a method that is

GET,HEAD, orPOST.

Only these three methods will not trigger a preflight.

As for CORS-unsafe request-header names, it will check whether the headers are all “CORS-safelisted request-header”. The definition of this can be found in section 2.2.2. Headers, and basically only the following will pass:

- accept

- accept-language

- content-language

- content-type

However, it should be noted that content-type has additional conditions and can only be:

- application/x-www-form-urlencoded

- multipart/form-data

- text/plain

The corresponding value of the above headers must also be valid characters. The definition of what constitutes valid characters varies for each header, so we won’t go into detail here.

If the request exceeds this range when sent, a preflight request will be sent.

Therefore, if you want to send JSON format data with a POST request, it will also trigger a preflight request, unless you use text/plain as the content-type (but it is not recommended to do so).

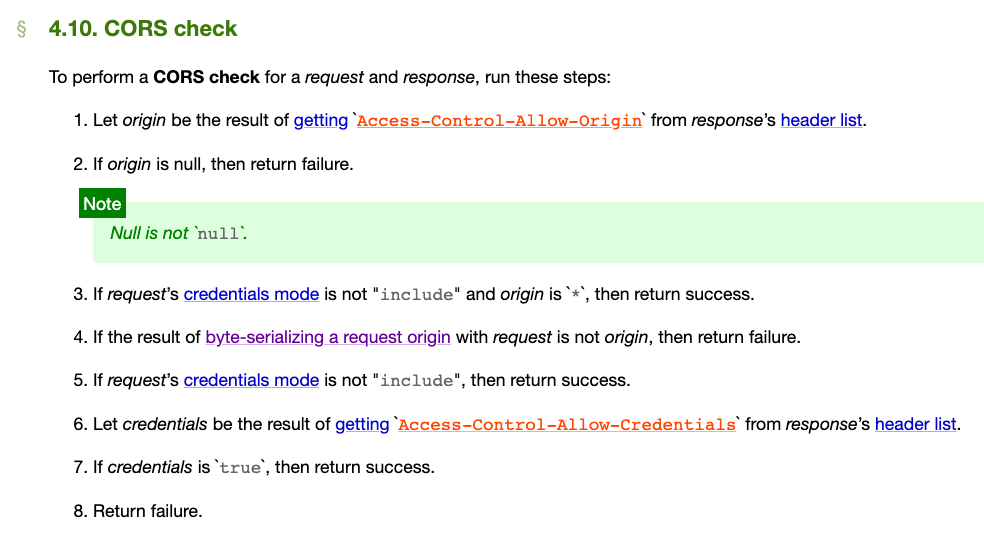

CORS check

Regarding the request part, we should have finished reading it. Next, let’s take a look at the response-related part. There is one thing I am curious about, which is how to verify that the CORS result has passed.

This can be seen in section 4.10. CORS check:

If the origin in Access-Control-Allow-Origin is null, it fails (it is emphasized here that it is null, not “null”, which we will discuss later).

Next, if the origin is * and the credentials mode is not include, it will pass.

Then compare the origin of the request with the one in the header. If they are different, it will return a failure.

If the origin is the same at this point, check the credentials mode again. If it is not include, it will pass.

Otherwise, check Access-Control-Allow-Credentials. If it is true, it will pass; otherwise, it will return a failure.

This series of checks has an early return flavor, which may be because it is easier to write in a list format and try to flatten the nesting as much as possible.

The above is almost all the specifications related to CORS. Chapter 6 mainly talks about the fetch API, and Chapter 7 talks about websockets.

Next, let’s focus on some other important content.

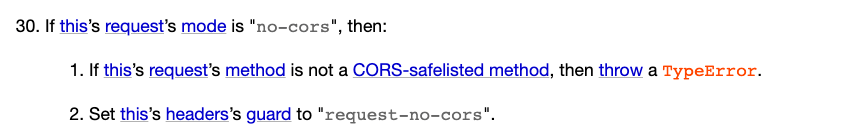

Misleading no-cors mode and fetch process

As mentioned earlier, fetch can set a mode: no-cors. Next, let’s take a look at what it actually does from the perspective of the specification.

Because this is a parameter of the fetch request, we need to start with 5.4 Request class, where there is a paragraph: The new Request(input, init) constructor steps are:

In step 30, you can see:

If the request method is not GET, HEAD, or POST, a TypeError will be thrown. In addition, the header's guard will also be set to request-no-cors.

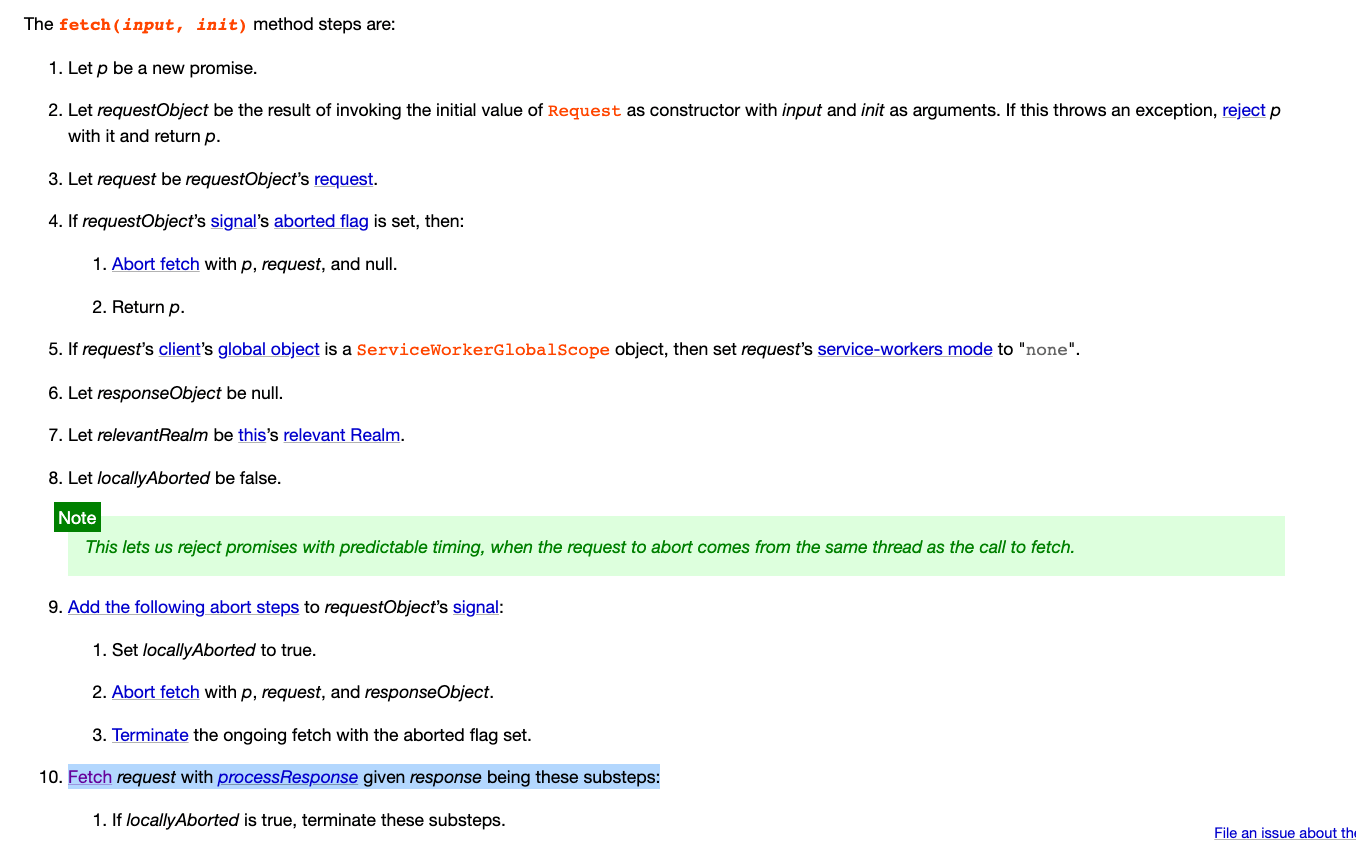

The above is just creating a new request. Next, you can refer to 5.6. Fetch method to see the actual process of sending the request:

The previous steps were just setting some parameters. The real action is in step ten:

Fetch request with processResponse given response being these substeps

That “Fetch” is a hyperlink that can be linked to the section 4. Fetching, and what we are concerned about here is the last step:

- Run main fetch given fetchParams.

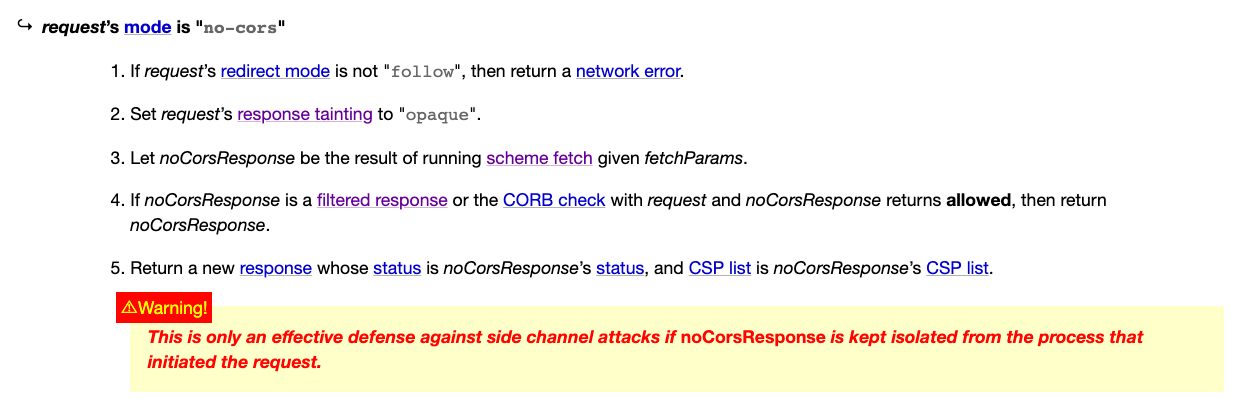

Main fetch is also a hyperlink that will take you to 4.1. Main fetch, where there is a whole section dedicated to handling the case when the mode is no-cors:

There are several things worth noting here:

- In step two, the response tainting of the request is set to opaque.

- In step three, the “scheme fetch” is executed.

- In step five, a new response is created with only status and CSP list.

- The warning below.

You can continue to trace back to the scheme fetch, just like before, and then follow different fetch methods, and the deeper you go, the more complicated it becomes. However, I have already traced it for you here, so assuming that step four is not valid, it will execute step five: “Return a new response whose status is noCorsResponse’s status, and CSP list is noCorsResponse’s CSP list.”

The warning part is actually quite important:

This is only an effective defense against side channel attacks if noCorsResponse is kept isolated from the process that initiated the request.

The reason for creating a new response here is that we don’t want to return the original response, we want to separate the original response from the process that initiated this request. Why do we do this? We will discuss this in the next article.

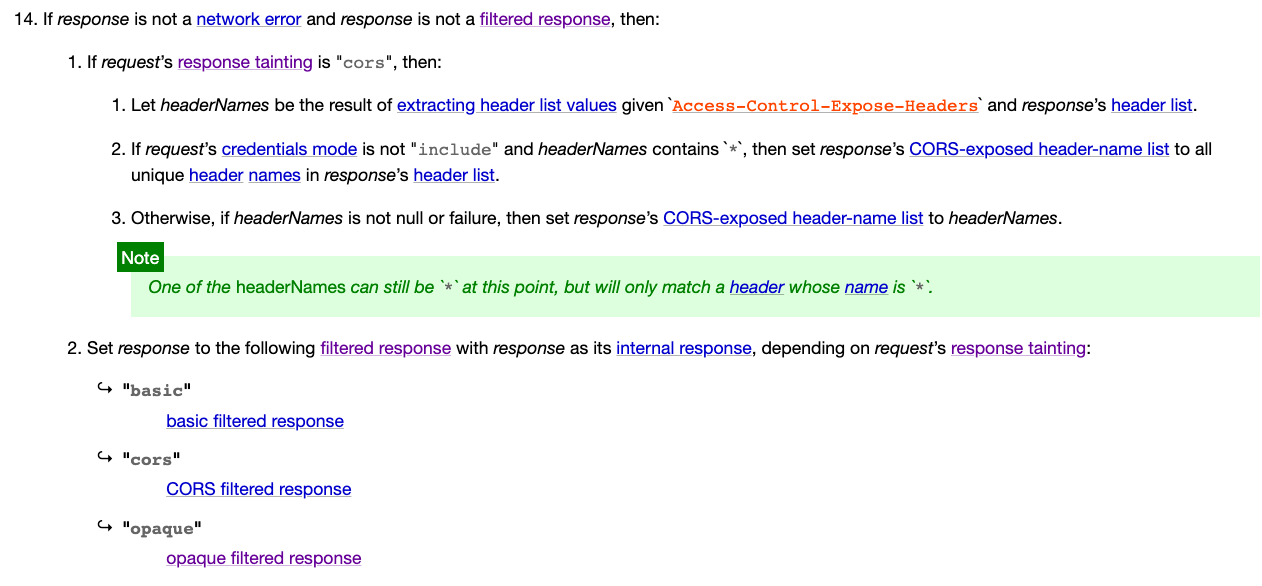

Next, let’s continue to look down, and you can see step fourteen:

The response tainting has been set to opaque, so according to step two, the response is set to opaque filtered response.

So what is this opaque filtered response?

An opaque filtered response is a filtered response whose type is “opaque”, URL list is the empty list, status is 0, status message is the empty byte sequence, header list is empty, and body is null.

This is the response we got when we used mode: 'no-cors', with a status of 0, no header, and no body.

In the specification, we have confirmed what I said earlier, that once the mode is set to no-cors, you cannot get the response, even if the backend sets the header.

Precautions when using CORS and cache

There is a paragraph in the specification: CORS protocol and HTTP caches that specifically discusses this.

Assume a scenario where the server only responds to requests with an origin header with the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header, and does not respond if there is no origin header (Amazon S3 does this). Then this response is cached, so the browser caches it.

Then let’s say we want to display an image, which is on S3, so it is cross-origin.

We put <img src="https://s3.xxx.com/a.png"> on the page, and the browser loads the image and caches the response. Because it is an img tag, the browser does not send an origin header, so the response naturally does not have Access-Control-Allow-Origin.

But then we also need to get this image in JS, so we use fetch to get it: fetch('https://s3.xxx.com/a.png'). At this point, it becomes a CORS request, so the request header will include the origin.

However, since we have already cached the response of this URL earlier, the browser will directly use the cached response that has not yet expired.

This is where the tragedy happens. The cached response we had earlier does not have the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header, so the CORS verification fails, and we cannot get the content of the image.

So how do we solve this situation? In the HTTP response header, there is a Vary that determines that the cache of this response may be different from some request headers.

For example, if Vary: Origin is passed, it means that if the origin header in the request I send later is different, then the previous cache should not be used.

In the case mentioned earlier, after setting this header, the request we send using fetch should not use the previously cached response because the Origin header is different from the one used with img earlier. Instead, it should send a new request.

I actually encountered this problem myself… please refer to: CORS is not as simple as I thought.

Conclusion

In this article, we looked at the fetch spec and looked at fetching resources from a specification perspective. We also confirmed many of the statements made in the previous articles from the specification. I highly recommend that you take some time to scan the spec, at least to have some impression of many things, which will make it easier to find information later.

In addition, you can also see some interesting parts of the specification, such as the caching problem mentioned at the end, which I actually encountered. If I had looked at the spec earlier, I would have been able to think of a solution faster when I encountered the problem.

When looking at the spec, you can also see that many things are done for security considerations. Next, let’s take a look at the penultimate article in this series: CORS Complete Manual (5): Security Issues Across Sources.

Comments