Introduction

Blogs need to display publishing time, restaurant websites need to display reservation time, and auction websites need to display various order times. No matter what you do, you will encounter the very common need to display time.

This problem seems simple, just display the time, right? But if it involves “time zones”, the problem will become even more complicated. Regarding time zones, there are usually several requirements:

- The time on the website needs to be displayed in a fixed time zone. I want to see the same time on the website whether I am in the United States or in Taiwan.

- The time on the website will be different according to the user’s browser settings. I will see different times in the United States and Taiwan.

- PM did not consider this issue and only considered local users, so there is no need to worry about this for the time being.

And this is only the display part. There is another part that communicates with the backend. We can talk about this later, but in any case, correctly handling time and time zones is not a simple matter.

I have recently encountered related issues in one or two jobs, so I have a little experience in this area and wrote this article to share with you.

Let’s start with timestamp

When it comes to time, I prefer to start with timestamp, or more precisely, Unix timestamp.

What is a timestamp? You open the console of devtool and enter: console.log(new Date().getTime()), and the thing that comes out is what we call a timestamp.

And this timestamp refers to: “From UTC+0 time zone, January 1, 1970, 0:00:00, how many milliseconds have passed in total”, and the value I got when writing this article is 1608905630674.

The ECMAScript spec is written like this:

20.4.1.1 Time Values and Time Range

Time measurement in ECMAScript is analogous to time measurement in POSIX, in particular sharing definition in terms of the proleptic Gregorian calendar, an epoch of midnight at the beginning of 01 January, 1970 UTC, and an accounting of every day as comprising exactly 86,400 seconds (each of which is 1000 milliseconds long).

The time in Unix systems is represented in this way, and the timestamp obtained by many programming languages is also similar. However, some may only be accurate to “seconds”, and some may be accurate to “milliseconds”. If you find that some places in the code need to be divided by 1000 or multiplied by 1000, it is likely to be doing the conversion between seconds and milliseconds.

We mentioned “UTC +0” above, which actually means +0 time zone.

For example, Taiwan’s time zone is +8, or if you want to be more standard, it is GMT +8 or UTC +8. The difference between these two can be found in: Is it GMT+8 or UTC+8?. The current standard is basically UTC, so this article will only use UTC from now on.

Standard format for storing time

After some basic concepts, let’s talk about how to store time. One way to store it is to store the timestamp mentioned above, but the disadvantage is that you cannot directly see what time it is with the naked eye, and you must go through conversion.

Another standard for storing time is called ISO 8601, which can be found in many places.

For example, OpenAPI defines a format called date-time, and its description is written like this:

the date-time notation as defined by RFC 3339, section 5.6, for example, 2017-07-21T17:32:28Z

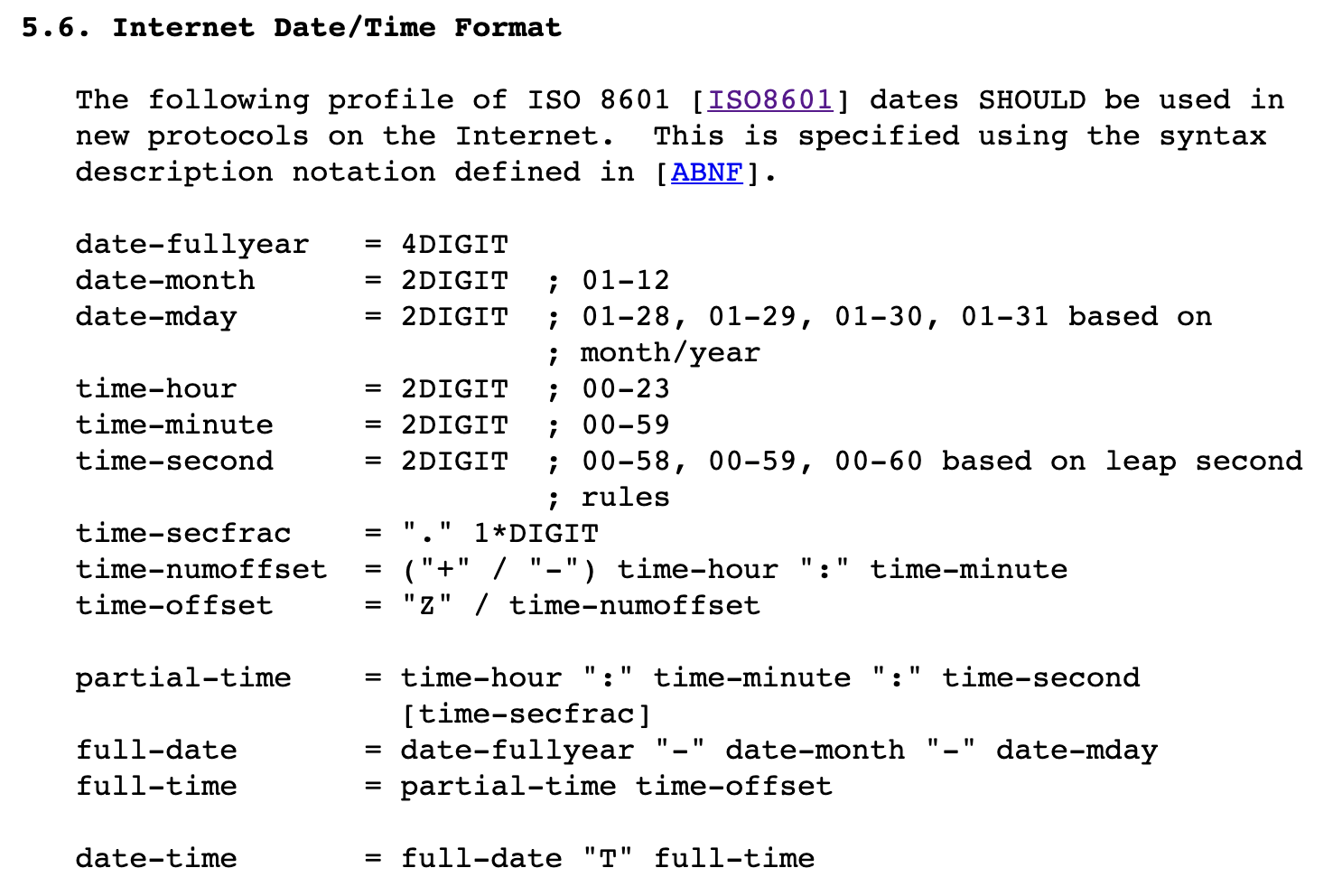

If you go directly to RFC 3339, the abstract at the beginning already states:

This document defines a date and time format for use in Internet protocols that is a profile of the ISO 8601 standard for representation of dates and times using the Gregorian calendar.

So what kind of format is this? It’s actually a string that represents a time with a time zone, like 2020-12-26T12:38:00Z.

For more detailed rules, you can refer to the RFC:

The rules defined in the RFC are more complete, but in general, it is the format I mentioned above. If the letter “Z” is at the end, it represents UTC+0. If you want to use another time zone, you can write it like this: 2020-12-26T12:38:00+08:00, which represents 12:38:00 on December 26th in the +8 time zone.

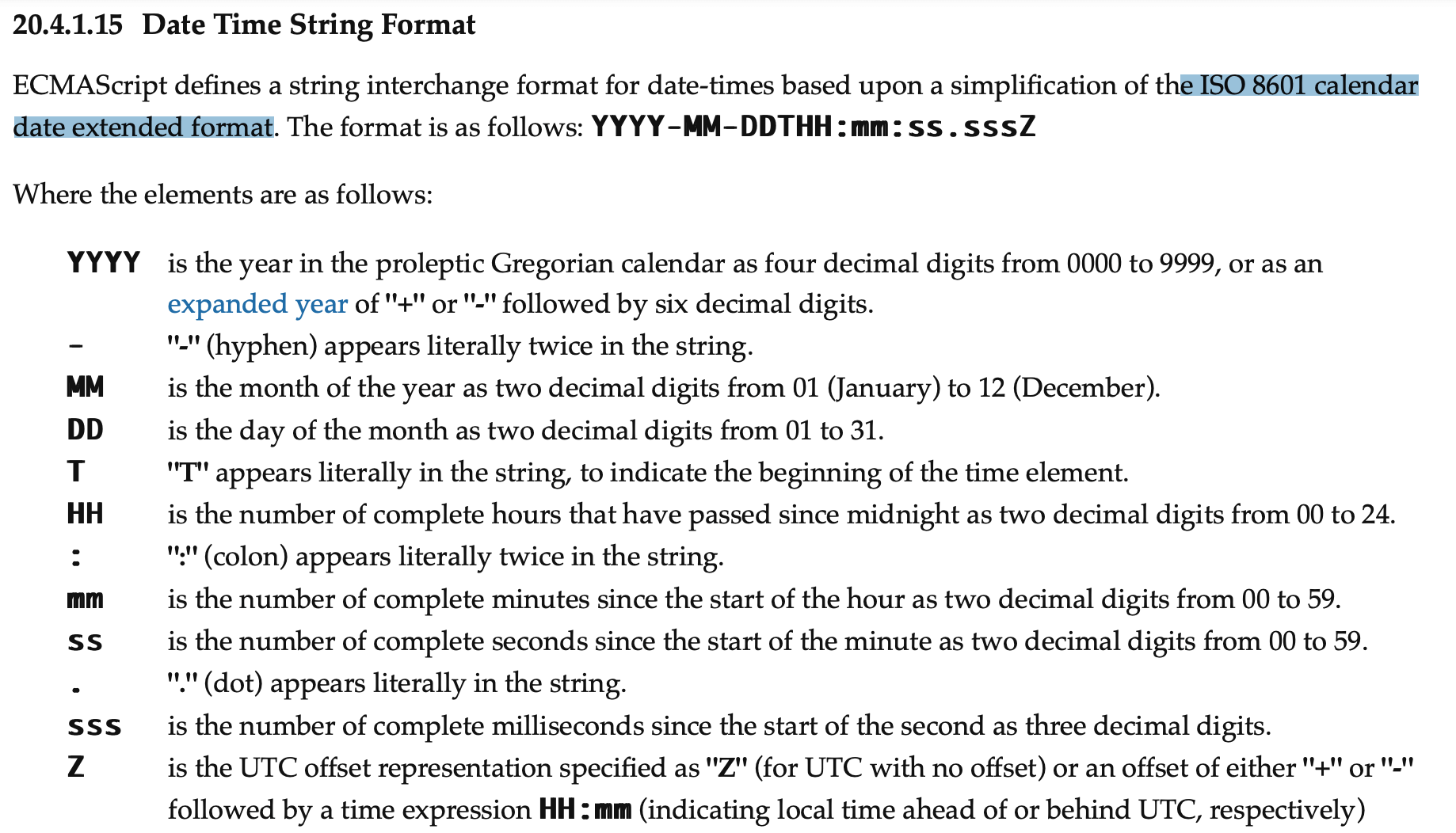

In JavaScript, it is based on an extended format of ISO 8601. In the ECMAScript spec, section 20.4.1.15 Date Time String Format mentions:

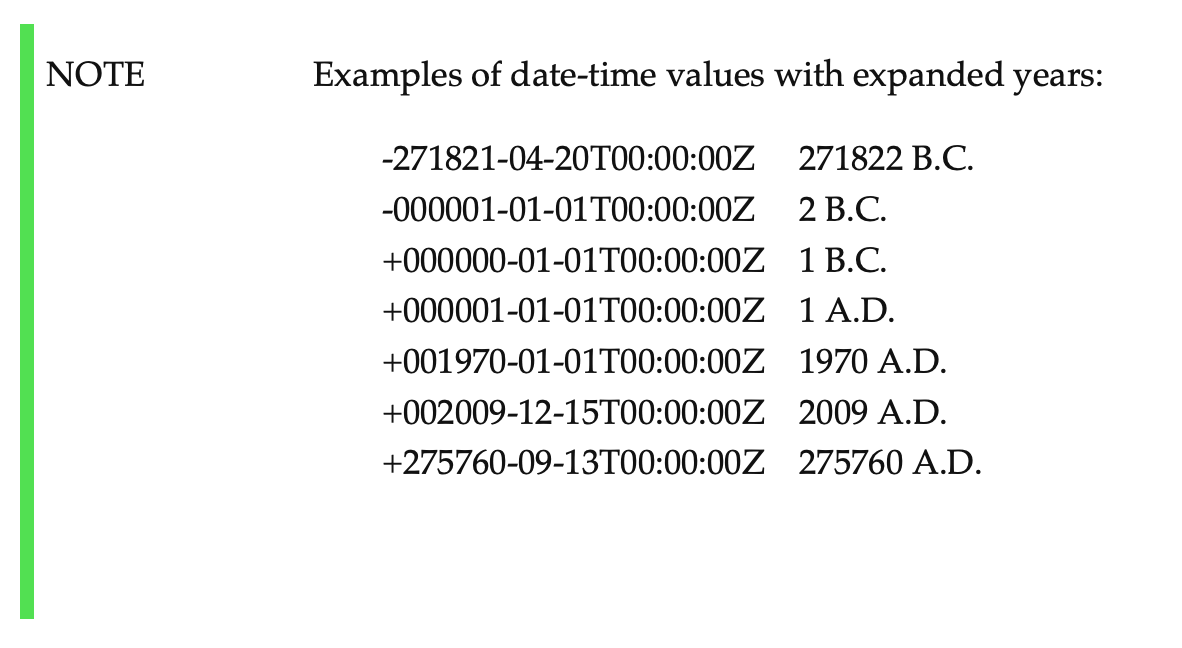

The most interesting part is the year, which, in addition to the well-known four-digit numbers from 0000 to 9999, can also be a six-digit number and can be negative, representing years before AD:

After understanding the standard format for representing time, there is an important concept to keep in mind, which is the relativity of time.

For example, the timestamp 1593163158 represents “June 26, 2020, 09:19:00 in UTC+0” and also represents “June 26, 2020, 17:19:00 in UTC+8”. These two times are the same.

Therefore, when you get a timestamp, you cannot know what time zone to display it in based on the timestamp itself.

After discussing these concepts, let’s talk about how to handle time in JavaScript.

Handling Time in JavaScript

In JavaScript, you can use Date to handle time-related requirements. For example, new Date() can generate the current time, and new Date().toISOString() can generate a string in ISO 8601 format, like 2020-12-26T04:52:26.255Z.

If you pass a parameter to new Date(), it will help you parse the time. For example, new Date(1593163158000) or new Date('2020-12-26T04:52:26.255Z').

In addition, there are many functions that can help you get various parts of the time. Using the string 2020-12-26T04:52:26.255Z as an example, we can use new Date('2020-12-26T04:52:26.255Z') with the following functions:

- getYear => 120

- getMonth => 11

- getDate => 26

- getHours => 12

- getMinutes => 52

- getSeconds => 26

- getMilliseconds => 255

Some parts look completely fine, but some parts look strange. Let’s explain the strange parts.

getYear

You might expect to get 2020, but you get 120 because getYear returns the year minus 1900. If you want to get 2020, use getFullYear.

getMonth

You might expect to get 12, but you get 11 because the number obtained here starts from 0. So if it is January, you get 0, so you get 11 for December.

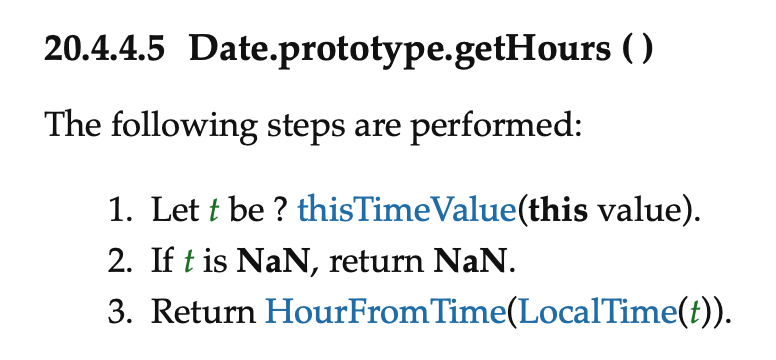

getHours

The time passed in is 4, so you expect to get 4, but you get 12. This is because before performing these operations, JS converts the time to “Local Time”:

Therefore, 4 o’clock in UTC+0 becomes 12 o’clock in UTC+8 after conversion, so you get 12.

Ignoring the feature of converting to local time, many people may wonder why the month needs to be subtracted by 1, and why getYear doesn’t return the year properly. These designs are not unique to JS, but were copied directly from Java 1.0.

Although JavaScript and Java are not really related now, their origins were very deep when JavaScript was first born (otherwise, why would it be named that way). It was originally hoped that the syntax would look like Java to attract Java developers, so it was reasonable to copy the entire java.util.Date from Java 1.0.

However, these designs were deprecated after JDK 1.1, but JavaScript still uses them for backward compatibility. You can still find explanations for getMonth and getYear in Java’s documentation.

And getYear returning results after -1900 was considered normal at the time because it was common to store only two digits for the year, such as 87 for 1987. This also led to the Year 2000 Problem (Y2K) where the year would become 00 in 2000.

These historical events are mentioned in “JavaScript: the first 20 years”, with the Java date section on page 19.

Things to note about date and time

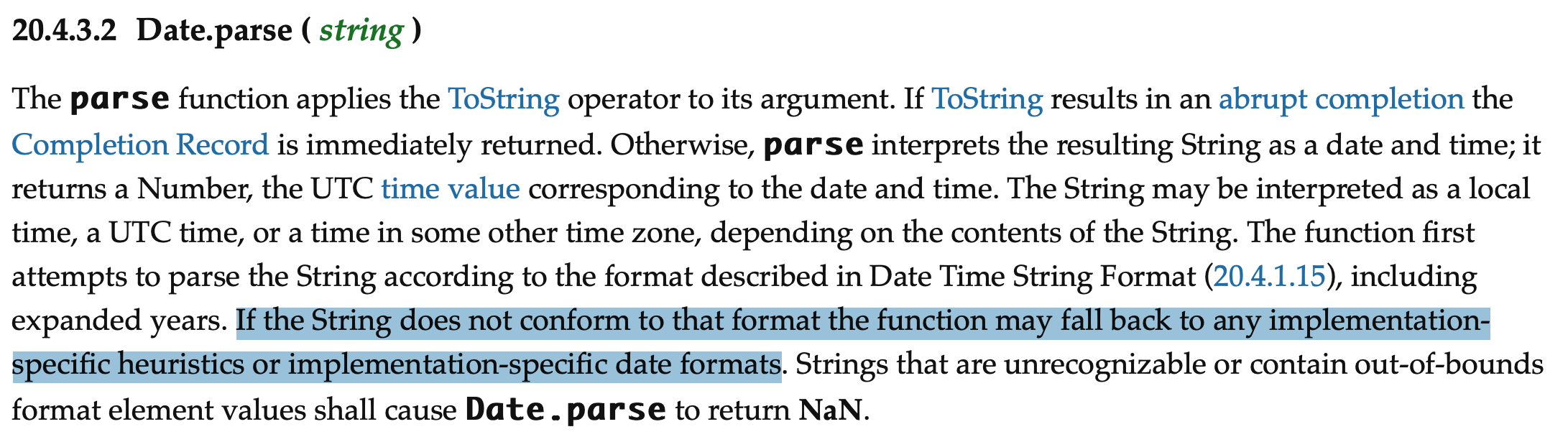

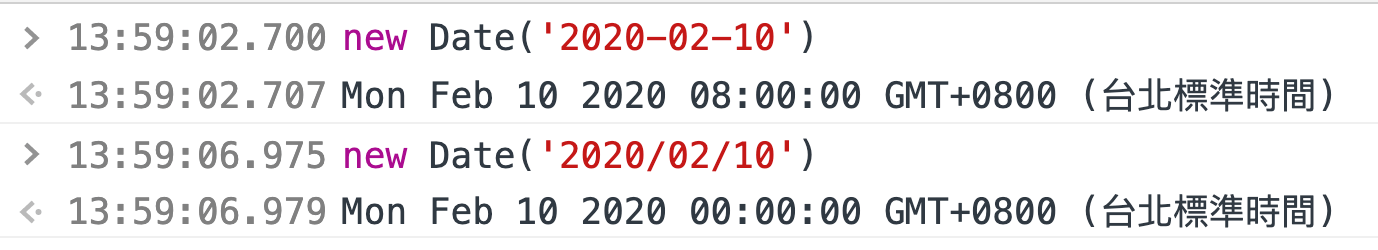

Using new Date(string) is equivalent to Date.parse(string), which allows JS to parse a string and convert it to a time. If the string you provide conforms to the standard format, there is no problem. However, if it does not conform to the standard, different results may occur depending on the implementation:

This is where you need to be careful. For example, these two strings:

new Date('2020-02-10')

new Date('2020/02/10')Aren’t they both February 10, 2020?

But if you run them on Chrome devtools, you’ll notice a slight difference:

According to the spec:

When the UTC offset representation is absent, date-only forms are interpreted as a UTC time and date-time forms are interpreted as a local time.

The former conforms to the ISO 8601 format, so it is parsed as February 10 at 0:00 UTC+0, which is why the result we see is 8:00 in the +8 time zone.

The latter does not conform to the ISO 8601 format, so different results may occur depending on the implementation. It appears that V8 treats the second format as local time. V8’s date parser is located here: src/date/dateparser-inl.h (although I haven’t found the exact line that causes this result yet).

Another common non-standard format is: 2020-02-02 13:00:00

This format is missing a T and will return an Invalid Date in Safari, but can be parsed correctly in Chrome. I think this is reasonable because you’re providing a non-standard format, which is invalid. The browser parsing it correctly is just an extra step, but you can’t blame it if it can’t parse it.

Note: Thanks to othree for the comment and discussion. There is actually a small detail here regarding ISO 8601 and RFC3339.

ISO 8601 states:

The character [T] shall be used as time designator to indicate the start of the representation of the time of day component in these expressions.

NOTE By mutual agreement of the partners in information interchange, the character [T] may be omitted in applications where there is no risk of confusing a date and time of day representation with others defined in this International Standard.

This means that in the ISO 8601 standard, the T character can be omitted if both parties agree, resulting in something like: 2020-02-0213:00:00, but it does not say that it can be replaced with a space.

In RFC3339, it is written:

NOTE: ISO 8601 defines date and time separated by “T”. Applications using this syntax may choose, for the sake of readability, to specify a full-date and full-time separated by (say) a space character.

So, RFC3339 allows using a space instead of T for readability. Therefore, a string separated by a space follows RFC3339 but not ISO 8601.

So, what about ECMAScript? According to the spec, it seems that T is also required. Therefore, in ECMAScript, a correct date time needs to use T to separate it and cannot be replaced by a space.

However, the interesting thing is that before ES5, the ECMAScript specification did not specify the format of date time. That is to say, there was no standard format, so omitting a T could still be parsed and treated as a behavior reserved for supporting previous implementations.

(Reference: In an ISO 8601 date, is the T character mandatory?, Allow space to separate date and time as per RFC3339)

Anyway, adding T will solve the problem, and after adding it, it will become a date time without a time zone: 2020-02-02T13:00:00.

When thrown into Chrome, it is: Sun Feb 02 2020 13:00:00 GMT+0800. When thrown into Safari, it is: Sun Feb 02 2020 21:00:00 GMT+0800.

According to the excerpt from the spec we posted above, if the time zone is missing and it is in date time format, it should be treated as local time. Therefore, Chrome’s approach is correct, but Safari treats this time as UTC +0 time, so it is eight hours behind.

I think this is a bug, but I didn’t find anyone reporting it in the WebKit bug tracker. Maybe there is a special reason for doing this.

These issues can also be referred to in Front-end Engineering Research: Common Pitfalls and Recommended Practices for the Date Type in JavaScript, which mentions more tests on browsers.

But the key principle is to use the standard format to communicate, and then there will be no such problems.

Finally, let’s talk about displaying time zones

After talking so much, we can finally talk about the problem of time zones mentioned at the beginning. When dealing with time, most people should choose a library that looks good to use, such as moment, date-fns, dayjs, or luxon. If these libraries are not used correctly, the results will be different from what you imagine.

For example, what will be the output of the following code?

luxon.DateTime

.fromISO('2020-02-02T13:00:00+03:00')

.toFormat('HH:mm:ss')…

…

…

Prevent Lightning

…

…

…

…

Many people mistakenly think that if your date time has a timezone, the formatted result will follow that timezone. But that’s not the case. The final format will still be based on local time.

Therefore, in the example above, since my computer is in the +8 time zone in Taiwan, the result will be 18:00:00 instead of 13:00:00.

You must remember this. Both dayjs and moment are the same. If the time zone is not specified before formatting, the formatted result will follow the user’s current time zone. Therefore, the same code may have different outputs on different users’ computers.

Therefore, what the server gives you is not important. Whether it is 2020-02-02T13:00:00+03:00, 2020-02-02T10:00:00Z, or 2020-02-02T18:00:00+08:00, it is the same for the front-end and represents the same time. Formatting will also produce the same result.

If you want to use the time zone in the date time as the main display, you can use it like this:

luxon.DateTime

.fromISO('2020-02-02T13:00:00+03:00', {

setZone: true

})

.toFormat('HH:mm:ss')But in most cases, it is recommended that the front-end decides which time zone to display, rather than relying on the date time given by the back-end.

So, how to decide which time zone to display? For luxon, it would be like this:

luxon.DateTime

.fromISO('2020-02-02T13:00:00+03:00')

.setZone('Asia/Tokyo')

.toFormat('HH:mm:ss')For moment, it would be like this:

moment('2020-02-02T13:00:00+03:00')

.tz('Asia/Tokyo')

.format('HH:mm:ss')dayjs is similar:

dayjs('2020-02-02T13:00:00+03:00')

.tz('Asia/Tokyo')

.format('HH:mm:ss')By doing this, we can ensure that the output time is always fixed to the same time zone. When would we need to do this? For example, the company I used to work for was a restaurant reservation website. The backend would send us the time slots available for booking, such as 1pm or 2pm in the afternoon. The backend would use a standard format to send us this information, such as: 2020-02-02T13:00:00+08:00, which represents the time slot available for booking at 1pm on February 2, 2020.

When displaying this information on the frontend, if we only use moment('2020-02-02T13:00:00+08:00').format('HH:mm'), it will appear correct on my computer and show 13:00. However, this is often the beginning of a bug because we assume it is correct just because it appears correct to us.

If we change to a different time zone, such as Japan, the result generated by the same code will be 12:00, which is an unexpected result. Since we are booking a restaurant in Taiwan, the booking time should be displayed in Taiwan time, not the user’s computer time zone.

At this point, we need to follow the rules mentioned above and use:

moment('2020-02-02T13:00:00+03:00')

.tz('Asia/Taipei')

.format('HH:mm:ss')to ensure that users in Japan or other places see the results displayed in Taiwan time.

Sending Time to the Backend

The previous section discussed how to correctly display a time given by the backend. The solution is to use the correct method to ensure that the time is displayed in a fixed time zone.

Another issue to be aware of is the opposite scenario, where the frontend needs to generate a date time and send it to the backend.

For example, continuing with the restaurant reservation website example, suppose there is a contact customer service page where the user needs to fill in the date to visit the restaurant, in the format: 2020-12-26. However, the data sent to the backend will be in date time format, so we need to convert it to the ISO 8601 standard format.

How would we do this?

Some people might think it’s simple. The native method is new Date('2020-12-26').toISOString(), or with other libraries it might be moment('2020-12-26').format(). However, this is incorrect.

Suppose the restaurant we are visiting is in Taiwan. Then, the date 2020-12-26 should be in Taiwan time, and the correct output should be 2020-12-26T00:00:00+08:00 or 2020-12-25T16:00:00Z, which is simply 0:00 on December 26 in Taiwan time.

The above code may generate “0:00 in UTC+0 time zone” or “0:00 in the user’s computer time zone”, and the generated date time will be incorrect, resulting in a time difference.

The correct way to use it is similar to before, where you need to call the timezone-related method, like this:

// moment

moment.tz('2020-12-26', 'Asia/Taipei').format()

// dayjs

dayjs.tz('2020-12-26', 'Asia/Taipei').format()to correctly tell the library that “this date is in Taipei, not in UTC or the user’s time zone”.

Summary

When dealing with time, the most common problem is adding or subtracting a day. Why does the user see December 25 instead of December 26? These problems are often related to time zones, and if time zones are not handled correctly, these basic problems will arise.

When dealing with time zones, as long as you remember a few principles, you can avoid these basic problems:

- Use standard format strings to communicate between frontend and backend.

- Let the frontend decide which time zone to display.

- When generating date time on the frontend, remember to consider whether to specify the time zone.

In addition to these, I also thought of some interesting problems, such as birthdays. Birthdays should be stored as a string instead of a date time string.

Suppose there is a large multinational website with a member system, and when registering, the user needs to fill in their birthday. If my birthday is December 26, 2020, and it is stored as a date time, it will be 2020-12-26T00:00:00+08:00.

Now, how do we display it? Which time zone should we use? It seems that using the Taiwan time zone to display it will not cause any problems, but the system also needs to know that I am Taiwanese in order to know which time zone to use. However, the system may not have this information.

So there seem to be two solutions. One is to store 2020-12-26 directly instead of a date time, and display it on the frontend as a string, not as a time. The other is to “store and display using UTC+0 time zone”, which should also not cause any problems.

Dealing with time is really not easy, and we often have many erroneous assumptions about time. You can refer to Your Calendrical Fallacy Is… and Falsehoods programmers believe about time zones, which mention many erroneous beliefs.

From the article, it can be seen that the native date object can no longer handle daily use, so whenever dealing with time, people usually use a library. Currently, there is a proposal worth paying attention to called Temporal, which is currently in stage 2 and hopes to become the future standard for handling date and time in JavaScript. For more detailed information, you can refer to this article: Temporal - Date & Time in JavaScript today! or this presentation: Temporal walkthrough.

Finally, if you use Jest to write tests, you can add process.env.TZ = 'Asia/Taipei'; to the config to specify the time zone for the tests to run, or you can directly pass it in as an environment variable.

My personal practice is to run tests in two different time zones to ensure that the tests pass correctly, rather than just getting lucky and writing the correct code.

Comments