Introduction

If you have written functions in other programming languages that are not first-class, you may experience some pain when writing JavaScript and wonder what you are doing - at least that’s how I feel.

When I first discovered that functions can be passed around as parameters, I had to think hard about more complex code, and other behaviors of functions also confused me, such as the fact that functions are also objects, and what exactly is this.

This article mainly wants to share some interesting aspects of functions. However, it is too boring to start talking about a lot of knowledge directly. I hope to arouse everyone’s curiosity about this knowledge. The best way to arouse curiosity is to provide a “question that you will also be interested in”. You will have the motivation to continue reading.

Therefore, the following uses a few small questions as the opening. Although they are in the form of questions, it doesn’t matter if you can’t answer them. If you are interested in the answers to these questions, please continue reading. If you are not interested, just go straight ahead and turn left at the end.

By the way, the title of this article was originally intended to be called “How much do you know about JavaScript functions” or “Interesting JavaScript functions”, but these titles are too boring, so I thought of this light novel-style (?) title.

Question 1: Named function expression

Generally, when writing a function expression, it is written like this:

var fib = function(n) {

if (n <= 1) return n

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

}

console.log(fib(6))But in fact, the function behind it can also have a name, for example:

var fib = function calculateFib(n) {

if (n <= 1) return n

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

}

console.log(calculateFib) // ???

console.log(fib(6))The question is:

- What is this function called, fib or calculateFib?

- What will the line

console.log(calculateFib)output? - Since it has already been named before, why is there an extra one at the end?

Question 2: apply and call

Everyone knows that there are basically three ways to call a function:

- Direct call

- call

- apply

As shown in the example below:

function add(a, b) {

console.log(a+b)

}

add(1, 2)

add.call(null, 1, 2)

add.apply(null, [1, 2])The question is:

- Why do we need call and apply besides the general function call? When do we need to use them?

Question 3: Creating functions

There are several ways to create functions, basically:

- Function declaration

- Function expression

- Function constructor

As shown below:

// Function declaration

function a1(str) {

console.log(str)

}

// Function expression

var a2 = function(str) {

console.log(str)

}

// 很少看到的 Function constructor

var a3 = new Function('str', 'console.log(str)')

a1('hi')

a2('hello')

a3('world')You can see that the keyword function must be included when declaring a function. Is there a way to create a function without using the function keyword?

At this point, some people may immediately think: Isn’t that an arrow function? Yes, so I have to add another restriction, which is not to use arrow functions. Some people may also think: What about methods on classes or objects? For example:

var obj = {

hello() {

console.log(1)

}

}

obj.hello()This is indeed a method, but I am not talking about methods on classes or objects, but a function that has nothing to do with objects, like: function add(a, b){}.

Can you think of any other methods?

Question 4: Black magic

There is a function called log, which accepts an object and prints the str property of the object:

function log(obj) {

console.log(obj.str)

}

log({str: 'hello'})Now, before printing, call another function. Please use magic in that function to change the output from hello to world:

function log(obj) {

doSomeMagic()

console.log(obj.str) // 要讓這邊輸出的變成 world

}

// 只能改動這個函式裡面的東西

function doSomeMagic() {

// 在這邊施展魔法

}

log({str: 'hello'})You can only modify the inside of the doSomeMagic function and add some code. How can you change things in another function? I would like to remind you that overwriting console.log is a solution, but unfortunately it is not what this article wants to discuss.

I hope these four questions have aroused your interest. The first two questions are really practical problems that you will encounter, and the last two questions are just for fun and basically cannot be touched. Next, we will not answer them one by one, but directly talk about the knowledge related to functions. We will answer the questions when we explain the relevant paragraphs.

Fun fun function

(Note: This title is actually a YouTube channel. I haven’t watched it much myself, but some of my students recommend it, so I recommend it to everyone.)

In JavaScript, a function is also an object, or more professionally speaking, a Callable Object, an object that can be called, and internally implements the [[Call]] method.

Since it is an object, you can manipulate it in any way that is like an object:

function add(a, b) {

return a + b

}

// 正常呼叫

console.log(add(1, 2))

// 當成一般物件

add.age = 18

console.log(add.age) // 18

// 當成陣列

add[0] = 10

add[1] = 20

add[2] = 30

add[3] = 40

add[4] = 50

for(let i=0; i<5; i++) {

console.log(i, add[i])

}Sharp-eyed friends may notice why the array side is i<5 instead of the common i<add.length. This is because add is a function, so add.length will be the total number of parameters, which is 2, and this property cannot be changed, so you cannot use add.length directly:

function add(a, b) {

return a + b

}

// 當成陣列

add[0] = 10

add[1] = 20

add[2] = 30

add[3] = 40

add[4] = 50

add.length = 100

console.log(add.length) // 2Using a function as a general object or an array is a situation that should be avoided because it will not happen in implementation. The most similar example is using an object as an array, the most well-known example of which is arguments inside a function, which is actually an “object-like object” or a pseudo-array or array-like object.

function add(a, b) {

console.log(arguments) // [Arguments] { '0': 1, '1': 2 }

console.log(arguments.length) // 2

// 像陣列一樣操作

for(let i=0; i<arguments.length; i++) {

console.log(arguments[i])

}

// 可是不是陣列

console.log(Array.isArray(arguments)) // false

console.log(arguments.map) // undefined

}

add(1, 2)So how do you make this object disguised as an array become an array? There are several ways, such as calling Array.from:

function add(a, b) {

let a1 = Array.from(arguments)

console.log(Array.isArray(a1)) // true

}Also, calling Array.prototype.slice:

function add(a, b) {

let a2 = Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments)

console.log(Array.isArray(a2)) // true

}At this point, we can answer the question raised earlier. Since a function can be called directly, why do we need the apply and call methods? One of the reasons is this. You can see that when calling slice, you don’t need to pass in the array, but directly call [1,2,3].slice(), which is related to the prototype, because the slice method is actually on Array.prototype:

console.log([].slice === Array.prototype.slice) // trueFor example, if we want to add a method called first to an array to return the first element, we would write it like this:

// 提醒一下,幫不屬於自己的物件加上 prototype 不是一件好事

// 應該盡可能避免

Array.prototype.first = function() {

return this[0]

}

console.log([1].first()) // 1

console.log([2,3,4].first()) // 2But you can see that this first method has only one line: return this[0], which can actually be used for objects as well. But if I want to use it on an object, I have to directly call Array.prototype.first and change this to apply it to the object I want.

So this is one of the reasons why apply and call exist. I need to change this to apply this function to where I want it, and in this case, I cannot call it like a normal function. Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments) is the reason for this.

You may have seen this usage of slice, but have you ever wondered why it works?

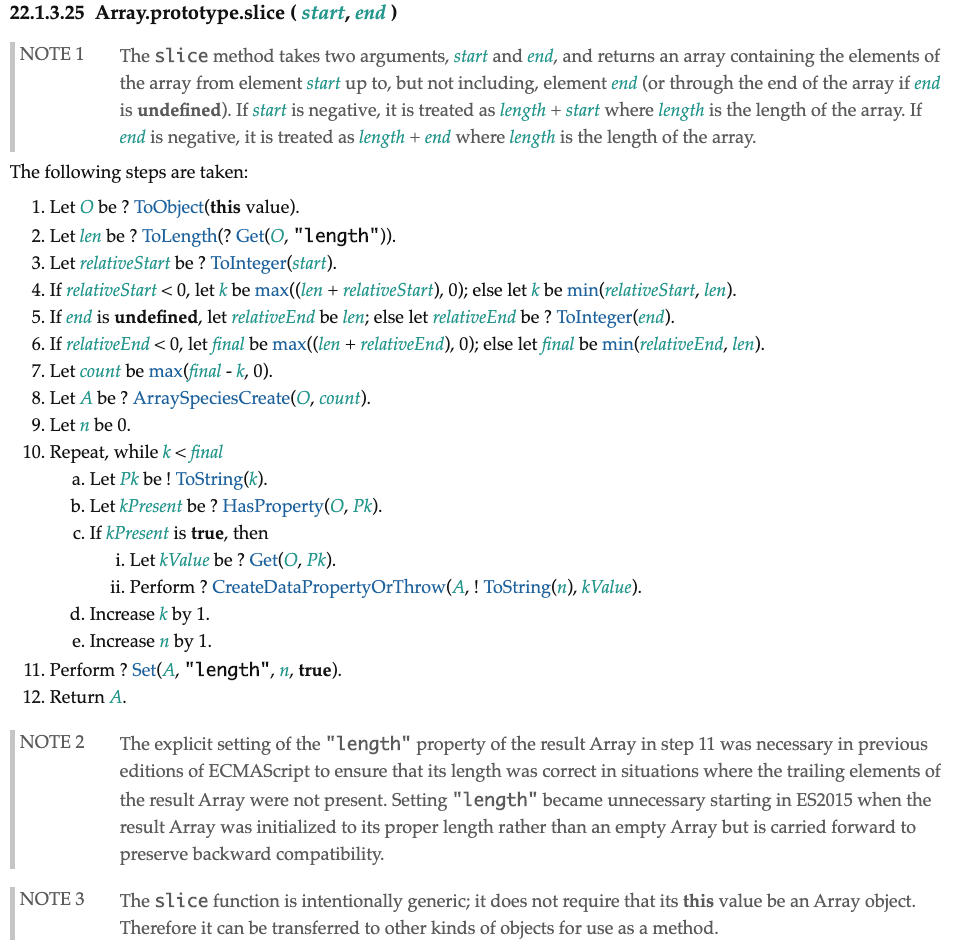

To understand the principle, you can refer to the ECMAScript Specification.

In 22.1.3.25 Array.prototype.slice, you can see the relevant explanation and operation method:

The first paragraph is the explanation of the parameters, the second paragraph is the operation steps, and the third paragraph is other additional explanations. You can first see the Note3 at the end:

The slice function is intentionally generic; it does not require that its this value be an Array object. Therefore it can be transferred to other kinds of objects for use as a method.

It is written here that this function can also be used on objects, not just arrays. Moreover, from the operation steps, you can see that HasProperty and Get are used, and objects also use these two, so it is completely okay to use them on objects.

And once you know the principle, you can also turn the function mentioned earlier into an array:

// 記得這邊參數一定要是三個,才能讓長度變成 3

function test(a,b,c) {}

test[0] = 1

test[1] = 2

test[2] = 3

// function 搖身一變成為陣列

var arr = Array.prototype.slice.call(test)

console.log(arr) // [1, 2, 3]Since we’ve mentioned call, let’s also mention the other two reasons we need to use call or apply. The first is when you want to pass multiple parameters, but you only have an array.

What does this mean? For example, the Math.max function can actually take any number of parameters, such as:

console.log(Math.max(1,2,3,4,5,6)) // 6If you have an array and you want to find the maximum value, what do you do? You can’t just call Math.max directly, because your parameter is an array, not individual numbers. If you call it directly, you will only get NaN:

var arr = [1,2,3,4]

console.log(Math.max(arr)) // NaNThis is where apply comes in handy. The second parameter is designed to take an array, so you can pass the array as a parameter:

var arr = [1,2,3,4]

console.log(Math.max.apply(null, arr)) // 4Or you can also use the spread operator in ES6:

var arr = [1,2,3,4]

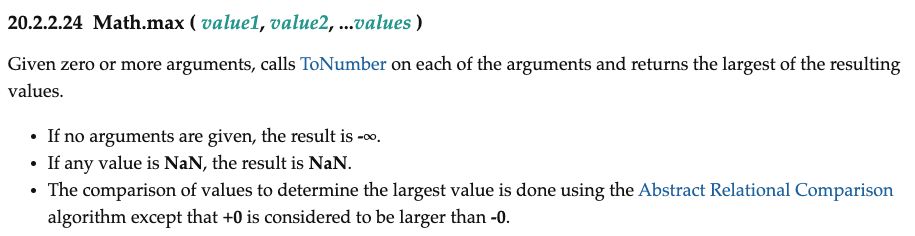

console.log(Math.max(...arr)) // 4Have you ever wondered why Math.max can take an unlimited number of parameters?

Actually, there’s no reason. The specification is written like this:

Next, regarding the second reason to use apply or call, let’s give you a scenario:

One day, Xiao Ming wanted to write a function to determine whether the parameter passed in was an object, and it couldn’t be an array or a function, just a normal object. He came up with a method called toString, recalling a few examples of toString:

var arr = []

var obj = {}

var fn = function(){}

console.log(arr.toString()) // 空字串

console.log(obj.toString()) // [object Object]

console.log(fn.toString()) // function(){}Since using toString on an object will result in [object Object], he used this to determine if it was a simple object. So Xiao Ming wrote this code:

function isObject(obj) {

if (!obj || !obj.toString) return false

return obj.toString() === '[object Object]'

}

var arr = []

var obj = {}

var fn = function(){}

console.log(isObject(arr)) // false

console.log(isObject(obj)) // true

console.log(isObject(fn)) // falseOkay, it looks very reasonable and can indeed determine if it’s a simple object. So what’s the problem?

The problem is on the line obj.toString(). It’s too naive. What if obj overrides the toString method itself?

function isObject(obj) {

if (!obj || !obj.toString) return false

return obj.toString() === '[object Object]'

}

var obj = {

toString: function() {

return 'I am object QQ'

}

}

console.log(isObject(obj)) // falseSo how can we ensure that the toString we call is the one we want to call?

Just like calling slice for an array, find the original function and use call or apply:

function isObject(obj) {

if (!obj || !obj.toString) return false

// 新的

return Object.prototype.toString.call(obj) === '[object Object]'

// 舊的

// return obj.toString() === '[object Object]'

}

var obj = {

toString: function() {

return 'I am object QQ'

}

}

console.log(isObject(obj)) // trueThis way, we can ensure that we are really calling the one we want, rather than relying on the original object, which may be at risk of being overwritten. These are some of the reasons why apply and call exist, which cannot be achieved with a normal function call.

(Note: The above method of judging objects may still fail in some cases, but I just want to demonstrate one of the reasons for the existence of call, not really wanting to write an isObject function.)

The mysterious variable that functions come with

Earlier, we mentioned that there is an automatically bound variable called arguments in a function that can get the parameter list. Although it looks like an array, it’s actually an object. And arguments actually has a magical feature, which is automatically bound to the parameters. Just look at the example below:

function test(a) {

console.log(a) // 1

console.log(arguments[0]) // 1

a = 2

console.log(a) // 2

console.log(arguments[0]) // 2

arguments[0] = 3

console.log(a) // 3

console.log(arguments[0]) // 3

}

test(1)If you change a, the parameters in arguments will also change; if you change arguments, a will also change. This behavior is closest to what we usually call call by reference, even if it is reassigned, it is still bound to the original thing.

I know about this behavior because of this article: JS Awakening Day12- Pass by Value, Pass by Reference and the reply from Liang Gege below, which made me realize that JS’s arguments still has this feature.

Speaking of which, do you remember the fourth question at the beginning?

function log(obj) {

doSomeMagic()

console.log(obj.str) // 要讓這邊輸出的變成 world

}

// 只能改動這個函式裡面的東西

function doSomeMagic() {

// 在這邊施展魔法

}

log({str: 'hello'})It’s using this feature of arguments:

function log(obj) {

doSomeMagic()

console.log(obj.str) // 要讓這邊輸出的變成 world

}

// 只能改動這個函式裡面的東西

function doSomeMagic() {

// magic!

log.arguments[0].str = 'world'

}

log({str: 'hello'})You can get the parameters passed in from another function using log.arguments, and then use the feature that arguments and formal parameters are synchronized with each other to modify the seemingly impossible obj.

What if we change the title?

(function(obj) {

doSomeMagic()

console.log(obj.str) // 要讓這邊輸出的變成 world

})({str: 'hello'})

// 只能改動這個函式裡面的東西

function doSomeMagic() {

}Without a function name, how can we get the arguments of that anonymous function?

Besides arguments, there are some parameters that are automatically passed in, such as the most common this, and a few uncommon ones, including [caller](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Function/caller). According to MDN:

The function.caller property returns the function that invoked the specified function. It returns null for strict, async function and generator function callers.

You can use caller to get which function called you, for example:

function a(){

b()

}

function b(){

console.log(b.caller) // [Function: a]

}

a()Now that we know this feature, the problem with the anonymous function above is easily solved:

(function(obj) {

doSomeMagic()

console.log(obj.str) // 要讓這邊輸出的變成 world

})({str: 'hello'})

// 只能改動這個函式裡面的東西

function doSomeMagic() {

doSomeMagic.caller.arguments[0].str = 'world'

}If you have never seen the caller parameter before, it’s okay because it should be avoided as much as possible in development. MDN also marks this feature as Deprecated and may be completely abandoned in the future. So, as I said at the beginning, this problem is purely for fun and has no practical teaching significance.

Do you think it’s over? I thought it was over too, until I thought of another extended question when writing this article: What if even doSomeMagic becomes an anonymous function?

(function() {

(function() {

// show your magic here

// 只能改動這個函式

})()

console.log(arguments[0].str) // 要讓這邊輸出的變成 world

})({str: 'hello'})Can we still achieve the goal?

Let’s leave that as a cliffhanger and answer it later.

Creating Functions

I wrote so much before finally talking about function declarations because I think they are relatively boring. As I mentioned earlier, there are mainly three ways to create functions:

- Function declaration

- Function expression

- Function constructor

Let’s talk about the third one first because it is almost never used in daily development, which is to use the function constructor to create a function:

var f = new Function('str', 'console.log(str)')

f(123)When we use the new keyword, we will call the constructor of the Function. If we don’t want to use new, we can write it like this:

var f = Function.constructor('str', 'console.log(str)')

f(123)Or you can just leave Function:

var f = Function('str', 'console.log(str)')

f(123)The key point here is the constructor. Let’s look at a simple example of JS object-oriented programming:

function Dog(name) {

this.name = name

}

Dog.prototype.sayHi = function() {

console.log('I am', this.name)

}

let d = new Dog('yo')

d.sayHi() // I am yoHere, d is an instance of Dog, so one of its features is that d.constructor will be the function called as the constructor, which is Dog:

function Dog(name) {

this.name = name

}

Dog.prototype.sayHi = function() {

console.log('I am', this.name)

}

let d = new Dog('yo')

d.sayHi() // I am yo

console.log(d.constructor) // [Function: Dog]What can we do with this feature? Since the constructor of any function is Function.constructor, isn’t it?

function test() {}

console.log(test.constructor) // [Function: Function]

console.log(test.constructor === Function.constructor) // trueCombined with what we mentioned earlier, we can use the function constructor to create a function like this:

function test() {}

var f = test.constructor('console.log(123)')

f() // 123Here, test can be any function, which means that we can find any built-in function and achieve the same effect:

var f1 = [].map.constructor('console.log(123)')

var f2 = Math.min.constructor('console.log(456)')

f1() // 123

f2() // 456In this way, we can achieve the goal of “creating new functions without using the function keyword or arrow functions”, which is the answer to problem three at the beginning.

Where is this usage usually used? It is used to bypass some checks! The common practice is to filter out the function keyword, eval, arrow functions, etc. to prevent others from executing the function. At this time, you can use constructor related things to bypass it. For example, this: Google CTF 2018 Quals Web Challenge - gCalc uses similar techniques.

After discussing function constructors, the only thing left is to talk about function declaration and function expression. Let’s start with the difference between the two:

// function declaration

function a() {}

// function expression

var b = function() {}The biggest difference between the two is that a actually declares a function named a, while b is “declaring an anonymous function and assigning it to variable b“. Also, b initializes the function only when it reaches that line of code, while a initializes when entering the code block. Therefore, you can execute a even before declaring it:

// function declaration

a()

function a() { }But b cannot:

// function expression

b() // TypeError: b is not a function

var b = function () {}This behavior is related to hoisting. For more information, please refer to: I know you understand hoisting, but how deep do you understand it?.

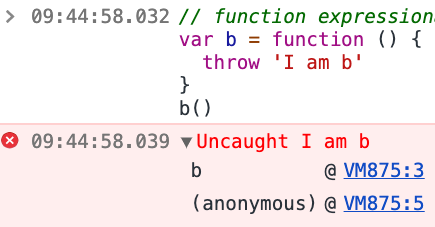

However, there is a mistake in one place above. I said that b is “declaring an anonymous function and assigning it to variable b“, but the function declared later actually has a name. You can throw an error to see:

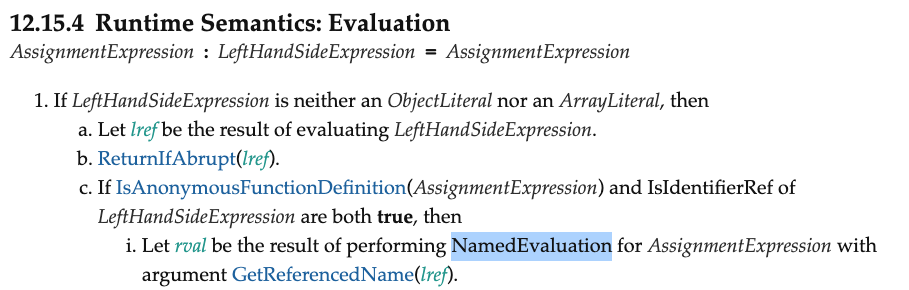

This function is actually called b, otherwise the stack trace record would write anonymous. This seemingly intuitive naming is actually a bit of a learning curve. This naming only takes effect when we assign the function to b. You can refer to 12.15.4 Runtime Semantics: Evaluation:

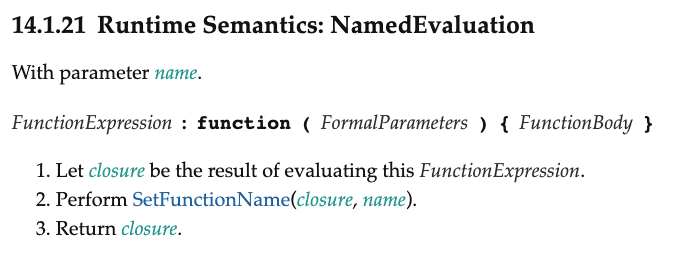

After obtaining the name you want to assign, call NamedEvaluation to name the function. You can refer to 14.1.21 Runtime Semantics: NamedEvaluation:

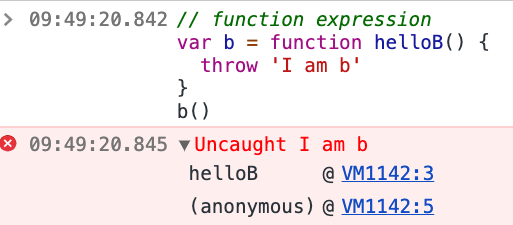

In addition to letting the JS engine automatically name it for you, you can also name it yourself. We call this a named function expression:

// function expression

var b = function helloB() {

throw 'I am b'

}

b()Don’t confuse it with function declaration. This is still not a function declaration, but a function expression with a name. It still initializes the function when it reaches that line of code, and the name helloB is not what you think it is. You cannot call it from outside:

// function expression

var b = function helloB() {

throw 'I am b'

}

helloB() // ReferenceError: helloB is not definedFor outsiders, it only sees the variable b, not helloB.

So what is the use of this function name? The first use is that it can be called inside the function:

// function expression

var b = function fib(n) {

if (n <= 1) return n

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

}

console.log(b(6)) // 8 The second is that the stack trace will also display this name instead of b:

At this point, you may not feel its benefits. Let me give you another example, which should be clearer. For example, the following code:

var arr = [1,2,3,4,5]

var str =

arr.map(function(n){ return n + 1})

.filter(function(n){ return n % 2 === 1})

.join(',')

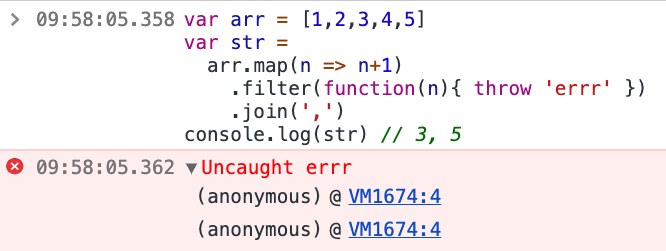

console.log(str) // 3, 5Although everyone is used to writing arrow functions now, basically it was written like this before the arrow appeared. You may have only noticed that we passed two anonymous functions, but more precisely, the parameters passed to map and filter are two different function expressions.

Suppose the function passed to filter has a problem:

var arr = [1,2,3,4,5]

var str =

arr.map(function(n){ return n + 1})

.filter(function(n){ throw 'errr' })

.join(',')

console.log(str) // 3, 5When we debug, we will see that the stack trace sadly only displays anonymous:

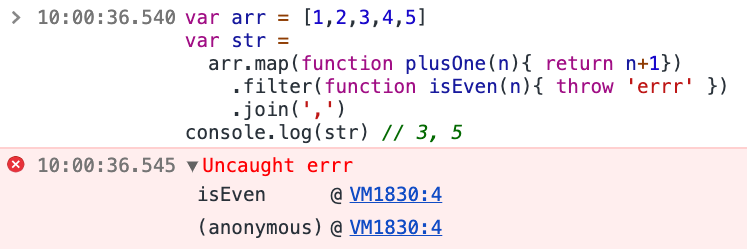

At this time, if we use a named function expression, we can solve this problem:

This is the benefit of using named function expressions.

As mentioned earlier, another benefit is that it can be called within the function, as shown in the example below:

function run(fn, n) {

console.log(fn(n)) // 55

}

run(function fib(n) {

if (n <= 1) return n

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

}, 10)run is just a shell that receives a function and a parameter, then calls the function and prints the execution result. Here we pass in a named function expression to calculate the Fibonacci sequence, and because of the need for recursion, we named the function.

What if an anonymous function is passed in? Can it also be recursive?

Yes, it can.

function run(fn, n) {

console.log(fn(n)) // 55

}

run(function (n) {

if (n <= 1) return n

return arguments.callee(n-1) + arguments.callee(n-2)

}, 10)The arguments object has a magical property called callee, which is explained on MDN as:

callee is a property of the arguments object. It can be used to refer to the currently executing function inside the function body of that function. This is useful when the name of the function is unknown, such as within a function expression with no name (also called “anonymous functions”).

In short, it can get itself, so even anonymous functions can be recursive.

Okay, so if that’s the case, do you all remember the question from earlier? The one about casting spells:

(function() {

(function() {

// show your magic here

// 只能改動這個函式

})()

console.log(arguments[0].str) // 要讓這邊輸出的變成 world

})({str: 'hello'})The answer is this very disgusting combination:

(function() {

(function() {

// show your magic here

// 只能改動這個函式

arguments.callee.caller.arguments[0].str = 'world'

})()

console.log(arguments[0].str) // 要讓這邊輸出的變成 world

})({str: 'hello'})First, use arguments.callee to get itself, then add caller to get the function that called itself, and then modify the parameters through arguments.

Answer time

Let’s answer some of the questions from earlier:

var fib = function calculateFib(n) {

if (n <= 1) return n

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

}

console.log(calculateFib) // ???

console.log(fib(6))1. Is this function called fib or calculateFib?

It’s called calculateFib, but you need to use fib outside the function to access it, and you can use calculateFib inside the function.

2. What will the line console.log(calculateFib) output?

ReferenceError: calculateFib is not defined

3. Since it already has a name, why add another one at the end?

- You can use this name when you want to call yourself

- This name will appear in the stack trace

4. Why do you need to use call and apply in addition to the normal function call? When do you need to use them?

- When we want to pass in an array, but the original function only supports one parameter at a time

- When we want to customize

this - When we want to avoid function overrides and directly call a function

5. Is there a way to create a function without using the function keyword?

Using the function constructor:

var f1 = [].map.constructor('console.log(123)')

var f2 = Math.min.constructor('console.log(456)')

f1() // 123

f2() // 4566. The doSomeMagic question

You can use various disgusting combinations of arguments.

Summary

This article summarizes some of my insights into JavaScript functions. Some of them are practical, and some are just for fun, such as the doSomeMagic question, which is just for fun. Basically, changing arguments or accessing caller and callee should be avoided in implementation because there is usually no reason to do so, and even if you really want to do something, there should be a better way.

As for the practical part, named function expressions are quite practical. Kyle Simpson, the author of YDKJS, advocates for using named function expressions and has put forward some benefits. For more information, please refer to: [day19] YDKJS (Scope) : Kyle Simpson 史上超級無敵討厭匿名函式(Anonymous function)

Then call and apply are questions I have thought about during my early days of learning programming. I wondered why we need them when we can directly call a function. When I saw Object.prototype.toString.call(obj) in some code, I also wondered why not just use obj.toString()? Later, I learned that it is to avoid function overrides. For example, an array is also an object, but its toString has been overridden to do something similar to join. That’s why we need to call Object.prototype.toString directly because that is the behavior we want.

This reminds me of some frontend interview questions that ask about the differences and usage of apply and call. I personally think that instead of asking that, it’s better to ask why we need apply and call as I did in this article. It would be more discerning and show if the person truly understands these two functions.

Anyway, that’s about it. If anyone finds any interesting features related to functions, whether practical or not, feel free to share them with me. I’m always interested to know!

Comments