After discussing the history and baggage of JavaScript, let’s talk about JavaScript itself.

Have you ever wondered how to know if an author of a JavaScript book or tutorial article has written it correctly? How do you know if the knowledge in the book is correct? As the title suggests, could it be that the JavaScript knowledge you previously knew was actually wrong?

Do you just trust the author because they often write technical articles? Or do you believe it because it’s written the same way on MDN? Or is it because everyone says it, so it must be right?

Some questions do not have standard answers, such as the trolley problem, where different schools of thought will have their own approved answers, and there is no saying which one is necessarily correct.

Fortunately, the world of programming languages is relatively simple. When we talk about JavaScript knowledge, there are two places where you can verify whether this knowledge is correct. The first is called the ECMAScript specification, and the second one, we’ll talk about later.

ECMAScript

In 1995, JavaScript was officially launched as a programming language that could run on Netscape. If you want to ensure cross-browser support, you need a standardized specification that all browsers can follow.

In 1996, Netscape contacted Ecma International (European Computer Manufacturers Association) and established a new technical committee (Technical Committee). Since it was numbered sequentially using numbers, it happened to be numbered 39 at that time, which is the TC39 we are familiar with now.

In 1997, ECMA-262 was officially released, which is the first version of what we commonly call ECMAScript.

Why is it called ECMAScript instead of JavaScript? Because JavaScript had already been registered as a trademark by Sun at that time and was not available for use by the Ecma Association, so it couldn’t be called JavaScript. Therefore, this standard was later called ECMAScript.

As for JavaScript, you can think of it as a programming language that implements the ECMAScript specification. When you want to know the specification of a certain JavaScript feature, it’s not wrong to look at ECMAScript, and the detailed behavior will be recorded in it.

Standards will continue to evolve, and new standards will appear almost every year, incorporating new proposals. For example, as of the time of writing, the latest is ECMAScript 12, which was released in 2021. It is usually referred to as ES12 or ES2021. The commonly heard ES6 is also called ES2015, representing the sixth version of ECMAScript released in 2015.

If you are interested in the history of ECMAScript and these terms, you can refer to the following articles:

- Twenty Years of JavaScript: Standardization

- Day2 [JavaScript Basics] A Brief Discussion of ECMAScript and JavaScript

- JavaScript Journey (1): Introduction to ECMA, ECMAScript, JavaScript, and TC39

Next, let’s take a brief look at what the ECMAScript specification looks like.

Exploring ECMAScript

You can find all versions of ECMAScript on this page: https://www.ecma-international.org/publications-and-standards/standards/ecma-262/

You can download the PDF directly or view the HTML version online. I would recommend downloading the PDF because the HTML seems to load all the content together, so it takes a long time to load, and there is a risk of crashing when paging.

When we open the ES2021 specification, we will find that it is a huge document with 879 pages. The specification is like a dictionary, it’s for you to look up, not for you to read like a storybook.

But as long as you can use the search function well, you can still quickly find the paragraph you want. Below, let’s take a look at the specifications of three different types of features.

String.prototype.repeat

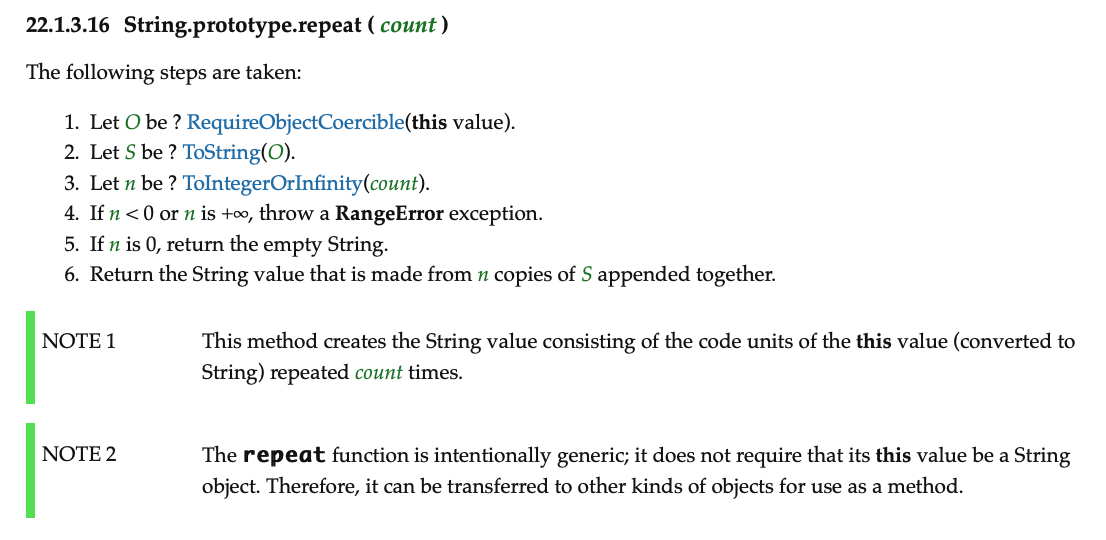

Search for “String.prototype.repeat”, and you can find the directory. Clicking on the directory will take you directly to the corresponding paragraph: 22.1.3.16 String.prototype.repeat, which is as follows:

You can try to read it yourself first.

Specifications are actually similar to programs, like pseudo code, so there are many programming concepts in them. For example, you will see many function calls above, and you need to check the definitions of other functions to understand exactly what they do. However, many functions can be inferred from their names, which shows that function naming is really important.

The above specification basically tells us two things that we may not have known before:

- If the count is negative or infinite when calling repeat, an error will occur.

- Repeat seems to not only work with strings.

The second point is actually quite important in JavaScript. In ECMAScript, you will also often see similar cases, which say “The xxx function is intentionally generic”. What does this mean?

Did you notice the first two steps, which are:

- Let O be ? RequireObjectCoercible(this value).

- Let S be ? ToString(O).

Aren’t we already dealing with strings? Why do we need to ToString again? And why is it related to this?

When we call "abc".repeat(3), we are actually calling the String.prototype.repeat function, and this is "abc", so it can be considered as String.prototype.repeat.call("abc", 3).

Since it can be converted into this call format, it means that you can also pass something that is not a string into it, for example: String.prototype.repeat.call(123, 3), and it will not break, it will return "123123123", and all of this is thanks to the extensibility of the specification definition.

Just now we saw in the specification that it was specially written that this function is intentionally written as generic, so it is not just strings that can be called, as long as it “can be converted into a string”, it can actually use this function. This is also why the first two steps in the specification are to convert this to a string, so that non-strings can also be used.

Here’s another even more interesting example:

function a(){console.log('hello')}

const result = String.prototype.repeat.call(a, 2)

console.log(result)

// function a(){console.log('hello')}function a(){console.log('hello')}Because functions can be converted into strings, they can of course be passed into repeat, and the toString method of the function will return the entire code of the function, so we get the output we saw at the end.

Regarding prototype and these things above, we will talk about prototype again later.

In short, from the specification, we can see a feature of ECMAScript, which is deliberately making these built-in methods more extensive and applicable to various types, as long as they can be converted into strings.

typeof

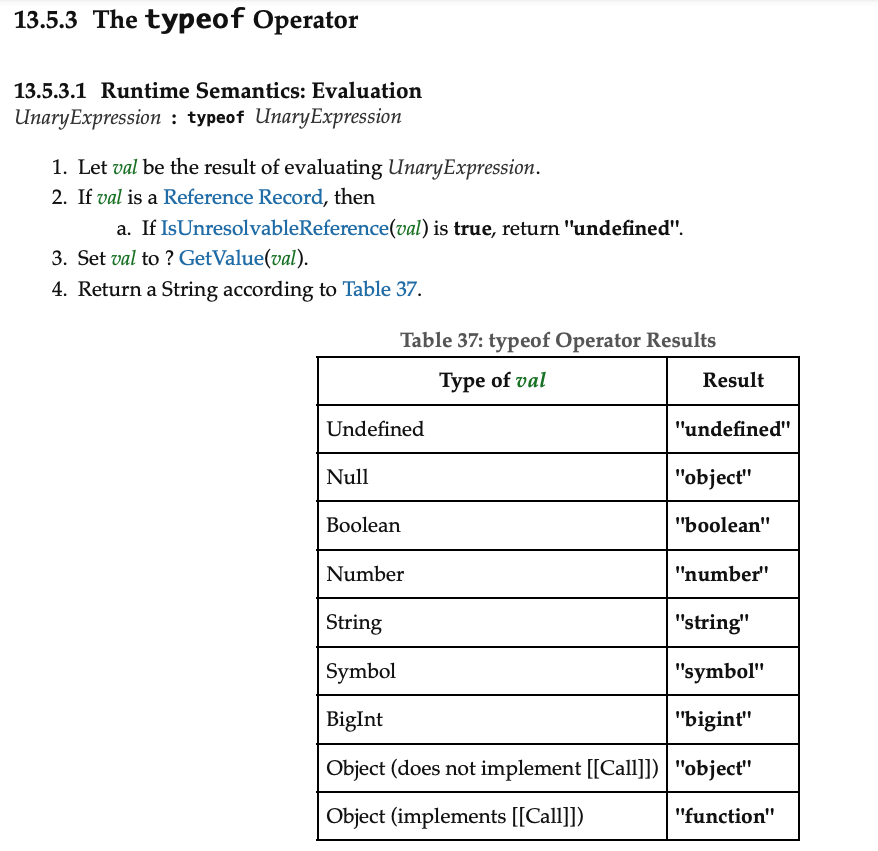

Similarly, searching for typeof in the PDF will find 13.5.3 The typeof Operator, with the following content:

We can see that typeof will perform some internal operations on the passed-in value, such as IsUnresolvableReference or GetValue, but usually we only care about the table below, which is what each type will return.

In the table, we can see two interesting things. The first thing is the famous bug, typeof null will return object, and this bug has become part of the specification today.

The second thing is that for the specification, objects and functions are actually both Object internally, the only difference is whether they have implemented the [[Call]] method.

In fact, if you look at other sections, you can also see that the term “function object” is used multiple times in the specification, which shows that in the specification, a function is just an object that can be called.

Comments

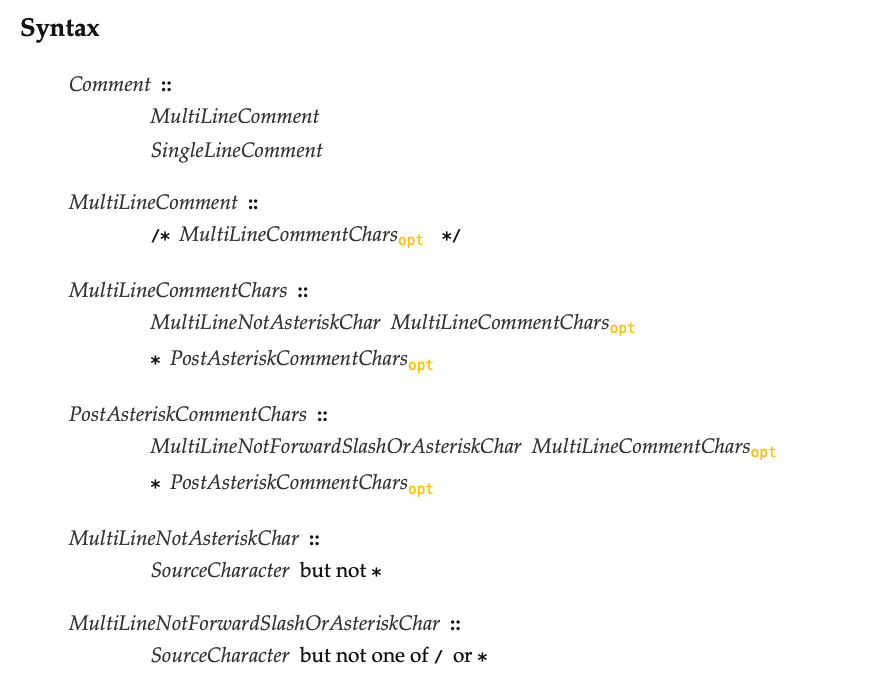

Next, let’s take a look at the syntax of comments. Searching for comments will find 12.4 Comments, and below is a partial screenshot:

We can see how ECMAScript represents syntax from top to bottom. Comments are divided into two types, MultiLineComment and SingleLineComment, and there are definitions for each below. MultiLineComment is /* MultiLineCommentChars */, and the yellow small font “opt” means optional, which means that MultiLineCommentChars can be omitted, such as /**/, and the definition continues below.

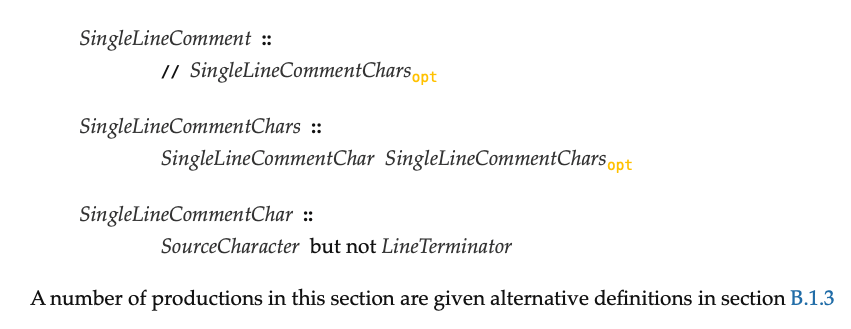

For single-line comments, it looks like this:

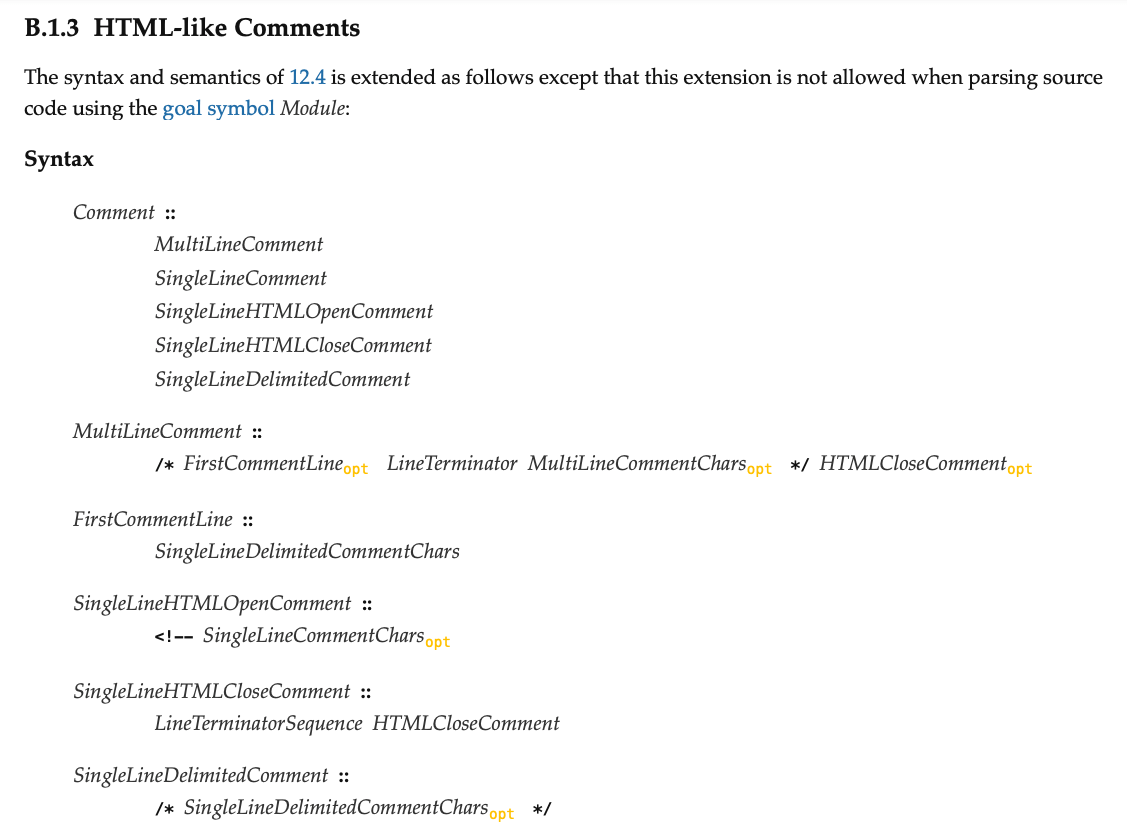

In fact, the meaning is similar to that of multi-line comments, and the last line guides us to B.1.3. Let’s take a look at the content there:

Here, HTML-like comments are additionally defined, and it looks like all of them are valid except for some special cases.

We can see that the definition of comments here has been further increased by three types:

- SingleLineHTMLOpenComment

- SingleLineHTMLCloseComment

- SingleLineDelimitedComment

From the specification, we can get new cold knowledge, which is that single-line comments not only have //, but also HTML comments can be used:

<!-- 我是註解

console.log(1)

// 我也是

console.log(2)

--> 我也是

console.log(3)This is a JavaScript cold knowledge that can only be seen from the specification.

When someone tells you that JavaScript comments only have // and /* */, if you have read the ECMAScript specification, you will know that what they are saying is wrong, and there is more than that.

The above are the three small paragraphs we found from ECMAScript, mainly to let everyone take a look at what the specification looks like.

If you are interested in reading the specification, I would recommend that you first read the ES3 specification, because ES3 is much more complete than the previous two versions, and the number of pages is small, only 188 pages, which can be read like a general book, one page at a time.

Although the wording and underlying mechanisms of the specification have changed somewhat since ES6, I think it is still good to start with ES3 to get familiar with the specification with minimal effort.

If you are interested in reading the specification and want to study it carefully, you can refer to the following two articles:

We mentioned earlier that there are two places where you can verify whether your JavaScript knowledge is correct. The first is the ECMAScript specification, and the second is something you should think about first.

Now it’s time to reveal the answer, and that is: “JavaScript engine source code.”

Talking about JavaScript engine source code

The ECMAScript specification defines how a programming language “should” be, but in fact, how it is actually implemented belongs to the “implementation” part. It’s like a PM defining a product specification, but an engineer may miss something and cause implementation errors, or may not be able to fully comply with the specification for various reasons, resulting in some differences.

So if you find a strange phenomenon in Chrome and find that the behavior is different from the ECMAScript specification, it is very likely that the implementation of the JavaScript engine in Chrome is actually different from the specification, which leads to this difference.

The specification is just a specification, and in the end, we still have to look at the implementation of the engine.

In the case of Chrome, it uses a JavaScript engine called V8 behind the scenes. If you know nothing about JS engines, you can first watch this video: Franziska Hinkelmann: JavaScript engines - how do they even? | JSConf EU.

And if you want to see the V8 code, you can see the official version: https://chromium.googlesource.com/v8/v8.git, or you can see this version on GitHub: https://github.com/v8/v8

When reading the ECMAScript specification, we looked at three different functions. Let’s take a look at how these functions are implemented in V8.

String.prototype.repeat

In V8, there is a programming language called Torque, which was born to make it easier to implement the logic in ECMAScript. The syntax is similar to TypeScript. For details, please refer to: V8 Torque user manual

The relevant code for String.prototype.repeat is here: src/builtins/string-repeat.tq

// https://tc39.github.io/ecma262/#sec-string.prototype.repeat

transitioning javascript builtin StringPrototypeRepeat(

js-implicit context: NativeContext, receiver: JSAny)(count: JSAny): String {

// 1. Let O be ? RequireObjectCoercible(this value).

// 2. Let S be ? ToString(O).

const s: String = ToThisString(receiver, kBuiltinName);

try {

// 3. Let n be ? ToInteger(count).

typeswitch (ToInteger_Inline(count)) {

case (n: Smi): {

// 4. If n < 0, throw a RangeError exception.

if (n < 0) goto InvalidCount;

// 6. If n is 0, return the empty String.

if (n == 0 || s.length_uint32 == 0) goto EmptyString;

if (n > kStringMaxLength) goto InvalidStringLength;

// 7. Return the String value that is made from n copies of S appended

// together.

return StringRepeat(s, n);

}

case (heapNum: HeapNumber): deferred {

dcheck(IsNumberNormalized(heapNum));

const n = LoadHeapNumberValue(heapNum);

// 4. If n < 0, throw a RangeError exception.

// 5. If n is +∞, throw a RangeError exception.

if (n == V8_INFINITY || n < 0.0) goto InvalidCount;

// 6. If n is 0, return the empty String.

if (s.length_uint32 == 0) goto EmptyString;

goto InvalidStringLength;

}

}

} label EmptyString {

return kEmptyString;

} label InvalidCount deferred {

ThrowRangeError(MessageTemplate::kInvalidCountValue, count);

} label InvalidStringLength deferred {

ThrowInvalidStringLength(context);

}

}As you can see, the comment is actually the content of the specification, and the code directly translates the specification. The actual implementation of the repeat function is as follows:

builtin StringRepeat(implicit context: Context)(

string: String, count: Smi): String {

dcheck(count >= 0);

dcheck(string != kEmptyString);

let result: String = kEmptyString;

let powerOfTwoRepeats: String = string;

let n: intptr = Convert<intptr>(count);

while (true) {

if ((n & 1) == 1) result = result + powerOfTwoRepeats;

n = n >> 1;

if (n == 0) break;

powerOfTwoRepeats = powerOfTwoRepeats + powerOfTwoRepeats;

}

return result;

}From here, we can see an interesting detail, which is that when repeating, it is not simply running a loop from 1 to n and then copying n times. This is too slow. Instead, it uses the square and multiply algorithm.

For example, if we want to generate 'a'.repeat(8), the usual method requires 7 additions, but we can first add once to generate aa, then add each other to generate aaaa, and finally add each other once more to get 8 repetitions using three additions (2^3 = 8), saving a lot of string concatenation operations.

From this, we can see that low-level implementations like JavaScript engines must also consider performance.

typeof

The definition of typeof in V8 is here, and the comment also mentions the relevant spec section: src/objects/objects.h#466

// ES6 section 12.5.6 The typeof Operator

static Handle<String> TypeOf(Isolate* isolate, Handle<Object> object);The implementation is here: src/objects/objects.cc#870

// static

Handle<String> Object::TypeOf(Isolate* isolate, Handle<Object> object) {

if (object->IsNumber()) return isolate->factory()->number_string();

if (object->IsOddball())

return handle(Oddball::cast(*object).type_of(), isolate);

if (object->IsUndetectable()) {

return isolate->factory()->undefined_string();

}

if (object->IsString()) return isolate->factory()->string_string();

if (object->IsSymbol()) return isolate->factory()->symbol_string();

if (object->IsBigInt()) return isolate->factory()->bigint_string();

if (object->IsCallable()) return isolate->factory()->function_string();

return isolate->factory()->object_string();

}As you can see, it checks for various types.

Some people may be curious about what Oddball is. null, undefined, true, and false are all stored using this type. I’m not sure of the exact reason, but if you want to delve deeper, you can refer to:

But if Oddball already includes undefined, why is there still a check below that also returns undefined? What is this undetectable?

if (object->IsUndetectable()) {

return isolate->factory()->undefined_string();

}All of this is due to historical baggage.

In the era when IE was prevalent, there was an IE-specific API called document.all, which could be used to get the specified element with document.all('a'). At that time, there was also a popular way to detect whether the browser was IE:

var isIE = !!document.all

if (isIE) {

// 呼叫 IE 才有的 API

}Later, Opera also followed suit and implemented document.all, but ran into a problem. Since it had implemented the IE-specific functionality, if a website used the above method to detect IE, it would be judged as IE. However, Opera did not have those IE-specific APIs, so the webpage would crash with an execution error.

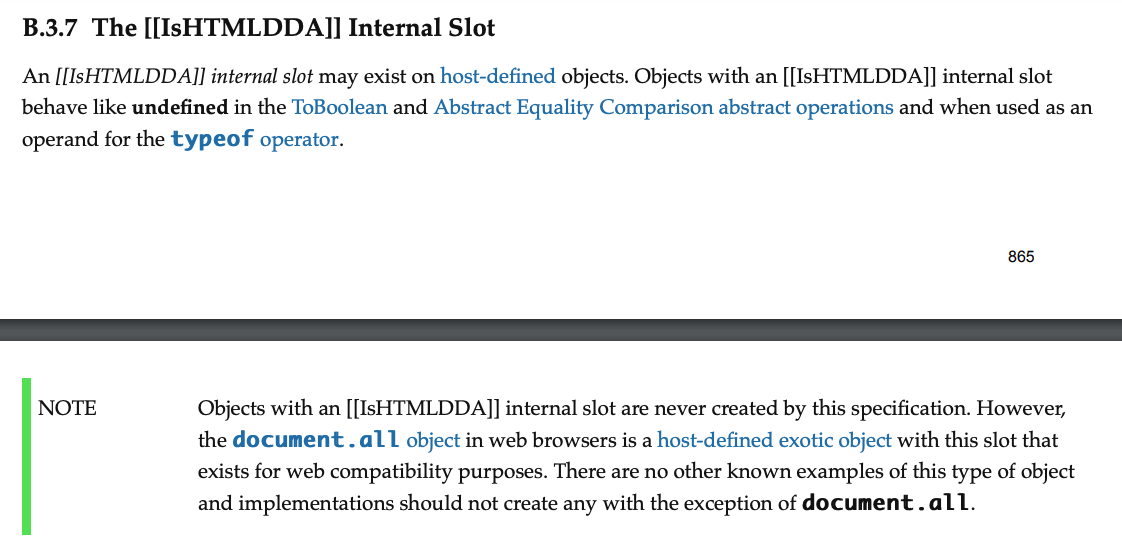

Firefox learned from Opera’s story when implementing this feature. Although it implemented the functionality of document.all, it did some tricks to prevent it from being detected:

typeof document.all // undefined

!!document.all // falseThat is, typeof document.all must be forced to return undefined, and when converted to a boolean, it must also return false. It’s really a master workaround.

Later, other browsers followed this implementation, and this implementation even became part of the standard, appearing in B.3.7 The [[IsHTMLDDA]] Internal Slot.

The IsUndetectable we see in V8 is generated to implement this mechanism. You can see it very clearly in the comments, and the code is in src/objects/map.h#391:

// Tells whether the instance is undetectable.

// An undetectable object is a special class of JSObject: 'typeof' operator

// returns undefined, ToBoolean returns false. Otherwise it behaves like

// a normal JS object. It is useful for implementing undetectable

// document.all in Firefox & Safari.

// See https://bugzilla.mozilla.org/show_bug.cgi?id=248549.

DECL_BOOLEAN_ACCESSORS(is_undetectable)At this point, you might want to open Chrome devtool and play with document.all to experience this historical baggage.

Chrome also had a bug because of this historical baggage. You can refer to What is the bug of V8’s typeof null returning “undefined” for the relevant story. The above paragraph is also written based on this article.

Comments

As mentioned earlier, JavaScript actually has several little-known comment formats, such as <!-- and -->. Regarding the syntax in V8, you can refer to this file: /src/parsing/scanner-inl.h. We extract a few paragraphs:

case Token::LT:

// < <= << <<= <!--

Advance();

if (c0_ == '=') return Select(Token::LTE);

if (c0_ == '<') return Select('=', Token::ASSIGN_SHL, Token::SHL);

if (c0_ == '!') {

token = ScanHtmlComment();

continue;

}

return Token::LT;

case Token::SUB:

// - -- --> -=

Advance();

if (c0_ == '-') {

Advance();

if (c0_ == '>' && next().after_line_terminator) {

// For compatibility with SpiderMonkey, we skip lines that

// start with an HTML comment end '-->'.

token = SkipSingleHTMLComment();

continue;

}

return Token::DEC;

}

if (c0_ == '=') return Select(Token::ASSIGN_SUB);

return Token::SUB;

case Token::DIV:

// / // /* /=

Advance();

if (c0_ == '/') {

base::uc32 c = Peek();

if (c == '#' || c == '@') {

Advance();

Advance();

token = SkipSourceURLComment();

continue;

}

token = SkipSingleLineComment();

continue;

}

if (c0_ == '*') {

token = SkipMultiLineComment();

continue;

}

if (c0_ == '=') return Select(Token::ASSIGN_DIV);

return Token::DIV;If you encounter <!, call ScanHtmlComment.

If you encounter --> and it is at the beginning, call SkipSingleHTMLComment. This paragraph also tells us one thing, that --> must be at the beginning, otherwise it will cause an error (here the beginning refers to no other meaningful statement before it, but spaces and comments are allowed).

If you encounter //, check if it is followed by # or @. If so, call SkipSourceURLComment. This is actually the syntax of source map. For details, please refer to sourceMappingURL and sourceURL syntax changed and How source map works.

Otherwise, call SkipSingleLineComment.

If it is /*, call SkipMultiLineComment.

The corresponding functions called above are all in src/parsing/scanner.cc. Let’s take a more interesting one, ScanHtmlComment, which will be called when encountering <!:

Token::Value Scanner::ScanHtmlComment() {

// Check for <!-- comments.

DCHECK_EQ(c0_, '!');

Advance();

if (c0_ != '-' || Peek() != '-') {

PushBack('!'); // undo Advance()

return Token::LT;

}

Advance();

found_html_comment_ = true;

return SkipSingleHTMLComment();

}Here, it will continue to look down and see if it is --. If not, it will undo the operation and return Token::LT, which is <. Otherwise, call SkipSingleHTMLComment.

The code for SkipSingleHTMLComment is also very simple:

Token::Value Scanner::SkipSingleHTMLComment() {

if (flags_.is_module()) {

ReportScannerError(source_pos(), MessageTemplate::kHtmlCommentInModule);

return Token::ILLEGAL;

}

return SkipSingleLineComment();

}According to the specification, check if flags_.is_module() is true. If so, throw an error. If you want to reproduce this situation, you can create a test.mjs file, use <!-- as a comment, and run it with Node.js to get an error:

<!-- 我是註解

^

SyntaxError: HTML comments are not allowed in modulesAnd <!-- can also cause a fun phenomenon. Most of the time, whether there are spaces between operators does not affect the result, for example, a+b>3 and a + b > 3 have the same result. But because <!-- is a complete syntax, so:

var a = 1

var b = 0 < !--a

console.log(a) // 0

console.log(b) // trueThe execution process is to first --a, make a 0, then ! to make it 1, and then 0 < 1 is true, so b is true.

But if you change < !-- to <!--:

var a = 1

var b = 0 <!--a

console.log(a) // 1

console.log(b) // 0Then there is no operation, because everything after <!-- is a comment. So it’s just var a = 1 and var b = 0.

By the way, when searching for implementation code, it is not easy to find what you are looking for in the vast sea of code. I’ll share a method I use, which is to use Google. You can directly search for keywords or use filters to search for code, like this: typeof inurl:https://chromium.googlesource.com/v8/v8.git.

If the code is on GitHub, you can also use this very useful website called grep.app to search for content in a specified GitHub repo.

Conclusion

When you obtain knowledge about JavaScript from anywhere (including this article), it may not necessarily be correct.

If you want to confirm, there are two levels to verify whether this knowledge is correct. The first level is “whether it conforms to the ECMAScript specification”, which can be achieved by finding the corresponding paragraph in ECMAScript. If I refer to ECMAScript in my article, I will try to attach the reference paragraph to facilitate everyone to verify it themselves.

The second level is “whether it conforms to the implementation of the JavaScript engine”, because sometimes the implementation may not be consistent with the specification, and there may be time issues, such as being included in the specification but not yet implemented, or even the other way around.

In fact, there is not only one JavaScript engine, and Firefox uses another engine called SpiderMonkey which is different from V8.

If you want to try reading the specification after reading this article, but don’t know where to start, I’ll give you a question to find the answer from the specification: “Assuming s is any string, are s.toUpperCase().toLowerCase() and s.toLowerCase() always equal? If not, please give a counterexample.”

Comments