This article is the text version of my presentation “Discovering the Depth of Front-end through Cybersecurity” at Modern Web 2021. The video of the talk is not yet available, but if you want to see the slides, you can find them here: slides

I personally think that the combination of video and slides would be better than text alone, but I thought it would be nice to have a written record, so I wrote this article. The content may differ slightly from the video, as it’s like rewriting it.

I Didn’t Know Front-end

This title is my most genuine thought after entering the world of cybersecurity.

As a front-end engineer, I thought I was quite familiar with front-end development. I have used or heard of native JavaScript, as well as some frameworks or libraries. I wasn’t too surprised when I saw many strange JavaScript questions, and I thought there was nothing that could make me say “Wow!”.

It wasn’t until I came into contact with cybersecurity-related things that I realized how naive I was.

The front-end that front-end engineers encounter is different from the front-end that cybersecurity engineers see. The focus of cybersecurity is on various attack methods, finding ways to bypass existing restrictions and finding a new path. But front-end engineers don’t need to know those things because they write code in an unrestricted environment.

Recently, I played some CTF and looked at front-end from another perspective. I learned a lot of new front-end knowledge. In other words, I re-learned the knowledge of my familiar field (front-end) in a new field (cybersecurity). This feeling is very special, so I want to share with you some of the things I learned in this article, hoping to make you feel the same surprise I felt at the beginning.

This article is divided into three main topics:

- Bypassing various restrictions

- XS leaks

- Other features you may not know

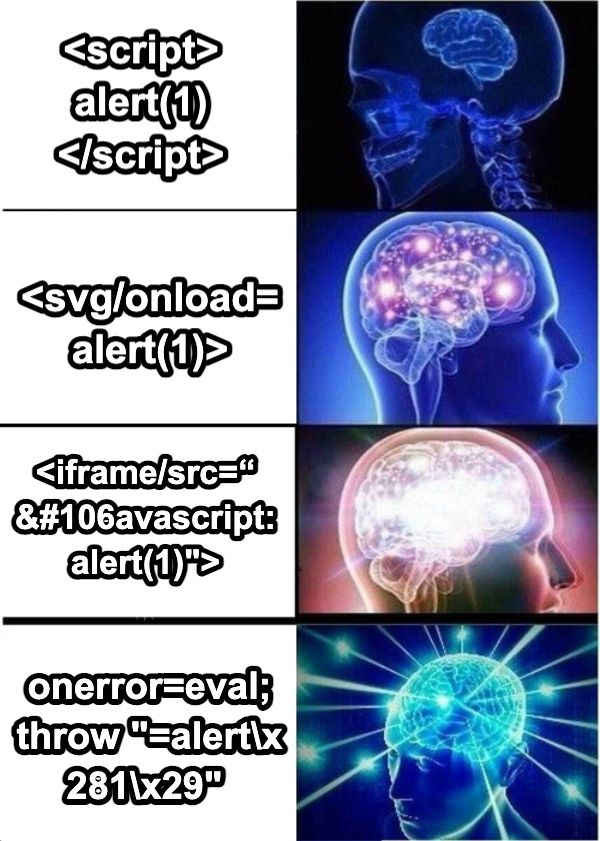

A simplest and most intuitive XSS payload would look like this:

<script>alert(1)</script>However, this form of XSS is not interesting enough and is easily defendable, so let’s not talk about it for now and look at some more interesting ones, such as this:

<img src=non_exist onerror=alert(1)>This HTML uses event handlers to execute JavaScript. We load a non-existent image, which triggers the onerror event and executes the code inside. It is also worth noting that the attribute does not need to be enclosed in "".

We can go further and make it look like this:

<svg onload=alert(1)>This time, we don’t even need a src, we just use <svg> with the onload event to execute the code.

Suppose Xiaoming is a backend engineer responsible for filtering these input strings to prevent XSS vulnerabilities. In addition to filtering <script>, Xiaoming also filters spaces. The reason is simple: for XSS that uses attributes to execute, there must be a space between the attribute and the tag, right? Once the spaces are filtered out, it is impossible to use attributes for XSS, right?

Naive Xiaoming hit a wall because it can be done like this:

<svg/onload=alert(1)>

<svg onload=alert(1)>

<svg

onload=alert(1)>In addition to spaces, /, tabs, and line breaks are all valid separators, so replacing only spaces is useless.

After Xiaoming learned this rule, he realized that the real problem was not spaces, but event handlers starting with onxxx. So he filtered out all attributes starting with on, thinking, “If there is no event handler, there is no XSS, right?”

It sounds very reasonable, but what he didn’t know was that even without event handlers, it can still be done like this:

<iframe/src="javascript:alert(1)">The string starting with javascript: is called a JavaScript pseudo protocol, which can be used in some places to execute code. We mentioned this feature in our previous post, “Open Redirect: What to Watch Out for When Implementing Redirect Functionality.”

Little Ming’s defense failed again, so he had to strengthen it again. He replaced the seemingly dangerous string javascript with something else. Shouldn’t that be enough to fix it?

Little did he know that inserting a tab between the letters of javascript still worked:

<iframe/src="javas cript:alert(1)">Little Ming fixed the code by replacing all the unnecessary things like spaces, blank lines, or tabs with empty strings, and then checked again for javascript. If it was found, it was filtered out. This way, the payload above would not work.

But Little Ming forgot that information on web pages can be encoded. For example, if you want to display <h1> on the screen, you need to encode it as <h1>. This way, the screen displays what you want, rather than interpreting it as an h1 tag. In addition to those special symbols, regular text can also be encoded using &#{ascii_code};. For example, the ascii code for j is 106, so it can be encoded as j:

<iframe/src="javascript:alert(1)">If you want, you can encode the entire string, leaving only some symbols and numbers.

Annoyed Little Ming gave up and disabled the src attribute, thinking, “If I disable src, everything will be fine, right? Don’t bother me anymore!”

But he forgot that <a> can also use this attribute:

<a/href="javascript:alert(1)">Click me</a>This time, it won’t trigger automatically. The user needs to click it to trigger it.

Finally, Little Ming couldn’t take it anymore, so he covered it with DOMPurify and ended this round.

In addition to these tag and attribute bypasses, JavaScript itself is also quite interesting to bypass. For example, “Is there a way to execute a function without using ()?”

If you’ve used React’s styled-components or something similar, you’ve probably written code like this:

const Box = styled.div`

background: red;

`Why does this generate a component? This is because backticks can be used not only as template strings, but also as function calls. I mentioned this in Intigriti’s 0521 XSS Challenge Solution: Limited Character Combination Code.

So you can write it like this:

alert`1`But what if you can’t even use backticks now? Is there any other way?

There is a method that I admired for a long time when I first saw it:

onerror=alert;throw 1It rewrites window.onerror to alert, and then throws an error. This error is caught by window.onerror because it is not caught, and finally executed in the alert.

In addition to alert, any code can be executed by rewriting it:

onerror=eval;

throw "=alert\x281\x29"The first line is the same as before, except that this time onerror is changed to eval. But what is the second line doing? Let’s talk about the encoding of () first, which are \x28 and \x29, respectively.

But why is there an = in front?

This is because when the error is thrown, if it is Chrome, the string it finally generates is: Uncaught {err_message}, such as throw 1, which will generate Uncaught 1. But this is not a JavaScript code, and it will directly throw an error when thrown into eval.

So we throw "=alert\x281\x29", which becomes Uncaught=alert\x281\x29, and the whole sentence becomes an expression. Uncaught is treated as an undeclared global variable, and its value is the return value of alert(1). In this way, the entire error message becomes legal JavaScript code! Using this method to throw to eval, it can be executed normally.

In fact, there are some more amazing methods, but the space is limited and some of them I am still trying to understand, so let’s stop here. The following figure summarizes:

Word Limit

In addition to the above attribute and character restrictions, there is another restriction called word limit.

For example, if a website’s nickname has an XSS vulnerability, but can only enter up to 25 characters, in this case, only popping up an alert is not powerful. Can you execute any code?

The shortest XSS payload <svg/onload=> already has 13 characters, leaving us with only 12 characters to execute the code. At this point, we need to use a technique called “using existing information,” like this:

// 13 + 18 = 31 characters

<svg/onload=eval(`'`+location)>This short code hides a lot of details. First of all, if you want to get the URL, how would you do it? location.href? A shorter way is to convert location to a string, and you can still get the URL. But the URL itself is not valid code, so we need to add a single quote in front of it, and then use the # on the URL, like this: https://example.com#';alert(1). Concatenate it with a single quote, and it becomes:

'https://example.com#';alert(1)This is a valid JavaScript code because it becomes a string followed by a command!

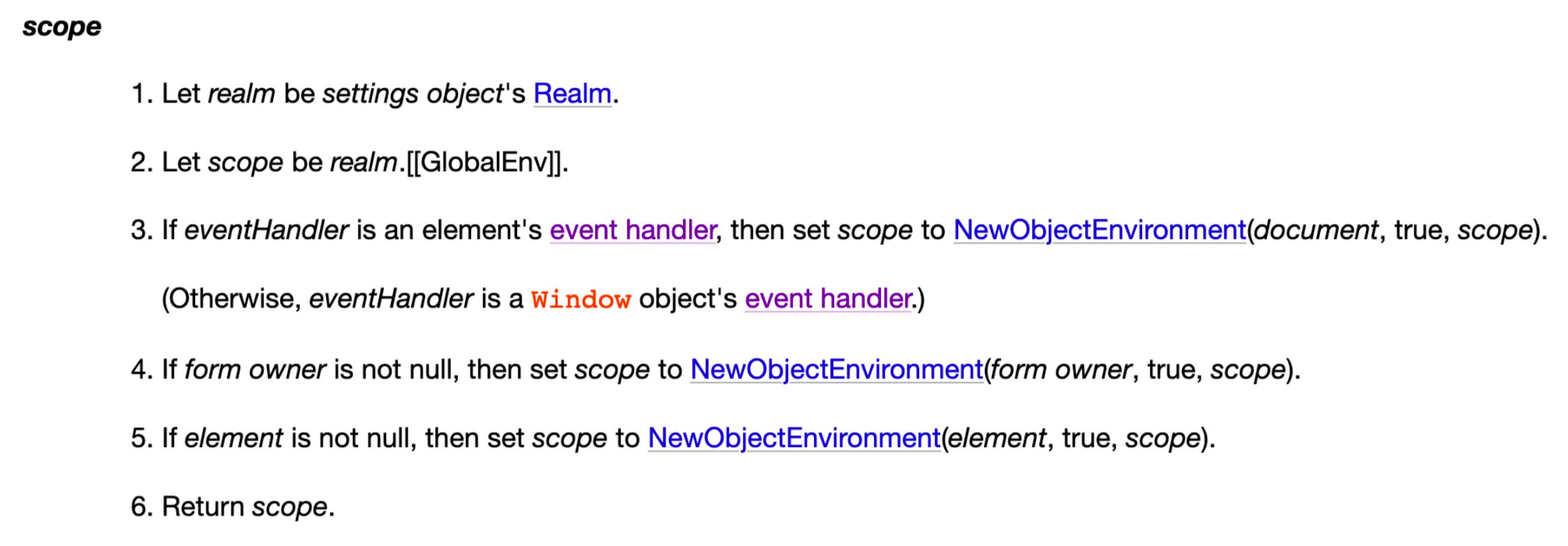

In addition to location, document.URL can also get the URL, but it has more characters than location. However, did you know that document can be omitted, like this:

// 13 + 13 = 26 characters

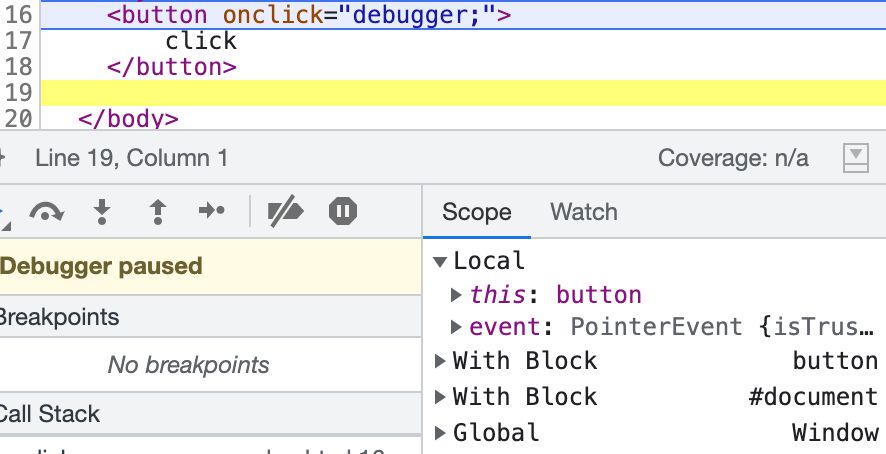

<svg/onload=eval(`'`+URL)>Why don’t we need to write document? This is because there is a hidden specification. In the inline code of the event handler, the default scope will have document:

It is also obvious when viewed with a debugger. Therefore, even if we only enter URL, we can still find document.URL due to the scope and the relationship with with.

We are only one character away from being under 25 characters. Are there any other tricks? Yes, please take a look at the code below. What do you expect the output to be?

name = 123

console.log(typeof name === 'number')It should be true, right? 123 is a number, which is very reasonable! But if you actually run it on a browser, you will find that the output is false because typeof name is a string!

This is because name is a special attribute that represents the name of the window or, simply put, the name of the page. In other words, even if the content is different, the same page will still share the same name!

Suppose the website I want to attack is example.com and my website is huli.tw. I can write it like this on my website:

<script>

name = 'alert(1)'

window.location = 'http://example.com'

</script>After setting the name, jump to the target website and then enter this payload:

// 13 + 10 = 23 characters

<svg/onload=eval(name)>Because of the sharing of name, I can successfully execute the code I want. This time, it only takes 23 characters, successfully compressed within 25 characters.

There is a website called Tiny XSS Payloades, which specializes in collecting these short payloads. There are more strange payloads inside. If necessary, you can refer to them. The payloads I know are also from this website.

XS leaks

After talking about some bypasses of restrictions, let’s take a look at another topic called Cross-Site Leaks (abbreviated as XS Leaks). This attack is actually a side-channel attack on the webpage. Regarding side-channel attacks, I mentioned it before in CORS Complete Manual (5): Security Issues of Cross-Origin, using the well-known Spectre as an example.

What is a side-channel attack? It means that you indirectly obtain information through some methods. For example, suppose you have a light bulb in front of you, but you can’t see it at all, and you can’t even feel the light source. How do you know if the light bulb is on or off?

One way is through “temperature”, because if the light bulb is on, it will emit light and may generate heat (assuming this premise is true and ignoring some edge cases, just for example). Therefore, when you touch the light bulb, you can feel the heat, which indirectly tells you whether the light bulb is on or off.

If we apply this concept to a webpage, it is similar. We can indirectly obtain information on the webpage through some methods. Let’s look at two examples.

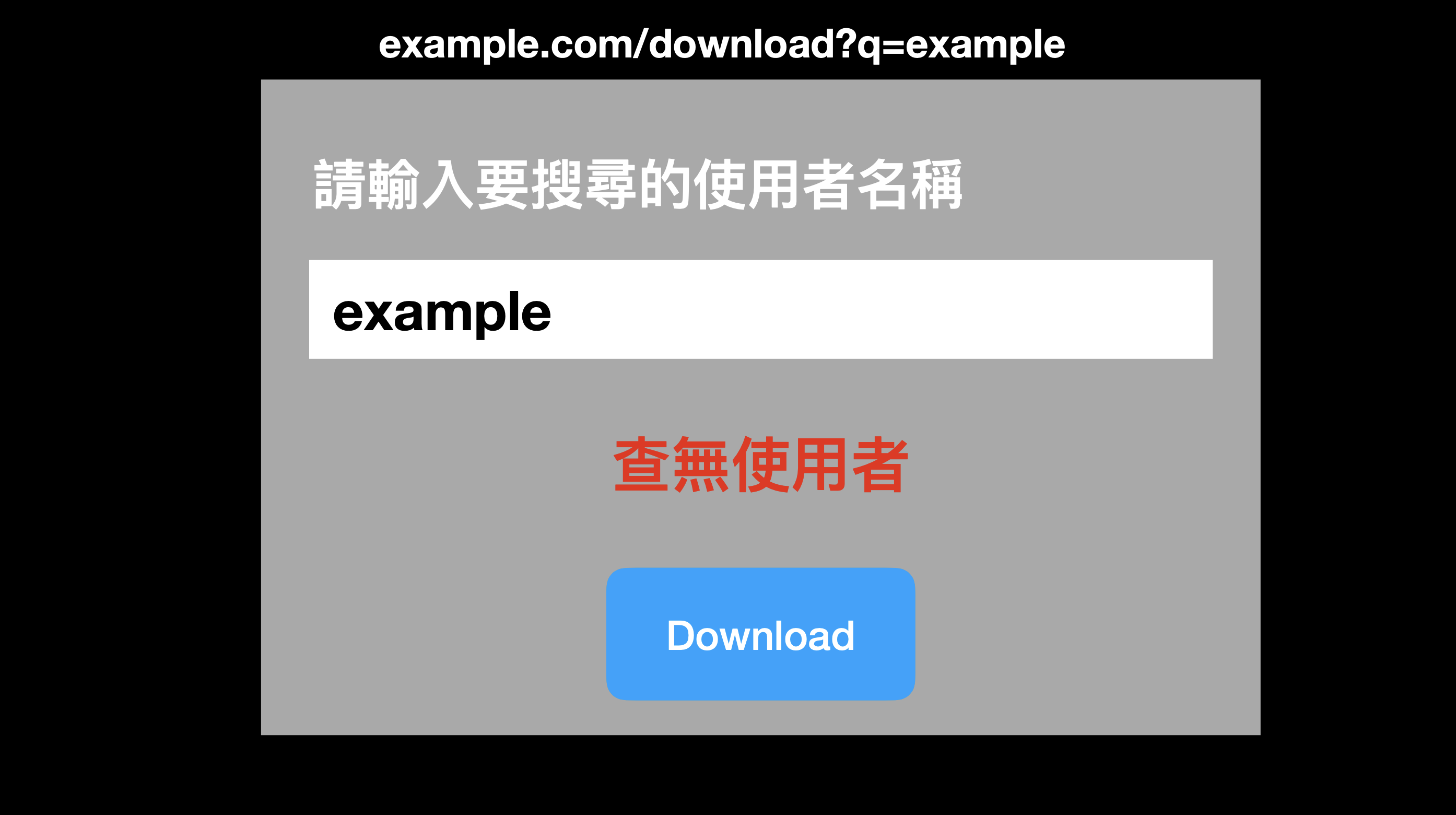

Search and Download

Suppose there is a website with a search and download function, and you can directly enter the string you want to search in the query string, for example, https://example.com/download?q=example. If there is no matching data in the database, a “No user found” page will appear:

On the other hand, if there is data, the native file download window will pop up directly, allowing you to download the corresponding file:

As an attacker, what can we do with this information?

Suppose I have my own website with the URL https://huli.tw, and then I embed the example website just now using an iframe on my website:

const iframe = document.createElement('iframe')

iframe.src = "https://example.com/download?q=user01"

document.body.appendChild(iframe)At this critical moment, if the data of user01 does not exist in the database, an error will occur when I try to access iframe.contentWindow.origin. This is because huli.tw and example.com are not the same origin websites, so they are blocked by the browser’s Same-Origin Policy.

But! If the data of user01 exists in the database, won’t the download screen pop up directly? At this time, if I try to access iframe.contentWindow.origin, there will be no error because I will get the result of null.

Therefore, based on the result of accessing iframe.contentWindow.origin, we can know whether a certain keyword exists in the database:

const iframe = document.createElement('iframe')

iframe.src = "https://example.com/download?q=user01"

document.body.appendChild(iframe)

// 先假設一秒後會載入完畢,可以做到更精確但先跳過

setTimeout(() => {

try {

iframe.contentWindow.origin

console.log('使用者存在')

} catch(err) {

console.log('使用者不存在')

}

}, 1000)This is XS leaks. We are clearly on website A, but we can use some techniques to obtain information from website B.

The complete attack implementation will extend the above attack script, for example, testing a first and then testing b, and so on. If b is found to exist, then repeat the above process to test ba, bb, etc., in this way, at least one set of user accounts can be leaked. Then, just send the link of this webpage to someone who has permission to access the https://example.com/download page and is logged in, and the attack will be launched when they click on it.

Although the pre-steps may sound a bit complicated, it is indeed a feasible attack method.

The mystery of id

Suppose there is a social networking site that boasts extremely high privacy. You cannot see who your friends’ friends are, cannot see mutual friends, so you don’t know who is friends with whom, only know who your friends are.

You and David, whose user id is 123, are good friends, so when you click on his profile page: http://example.com/users/123, you will see a “Send Message” button, and the id of the button is message:

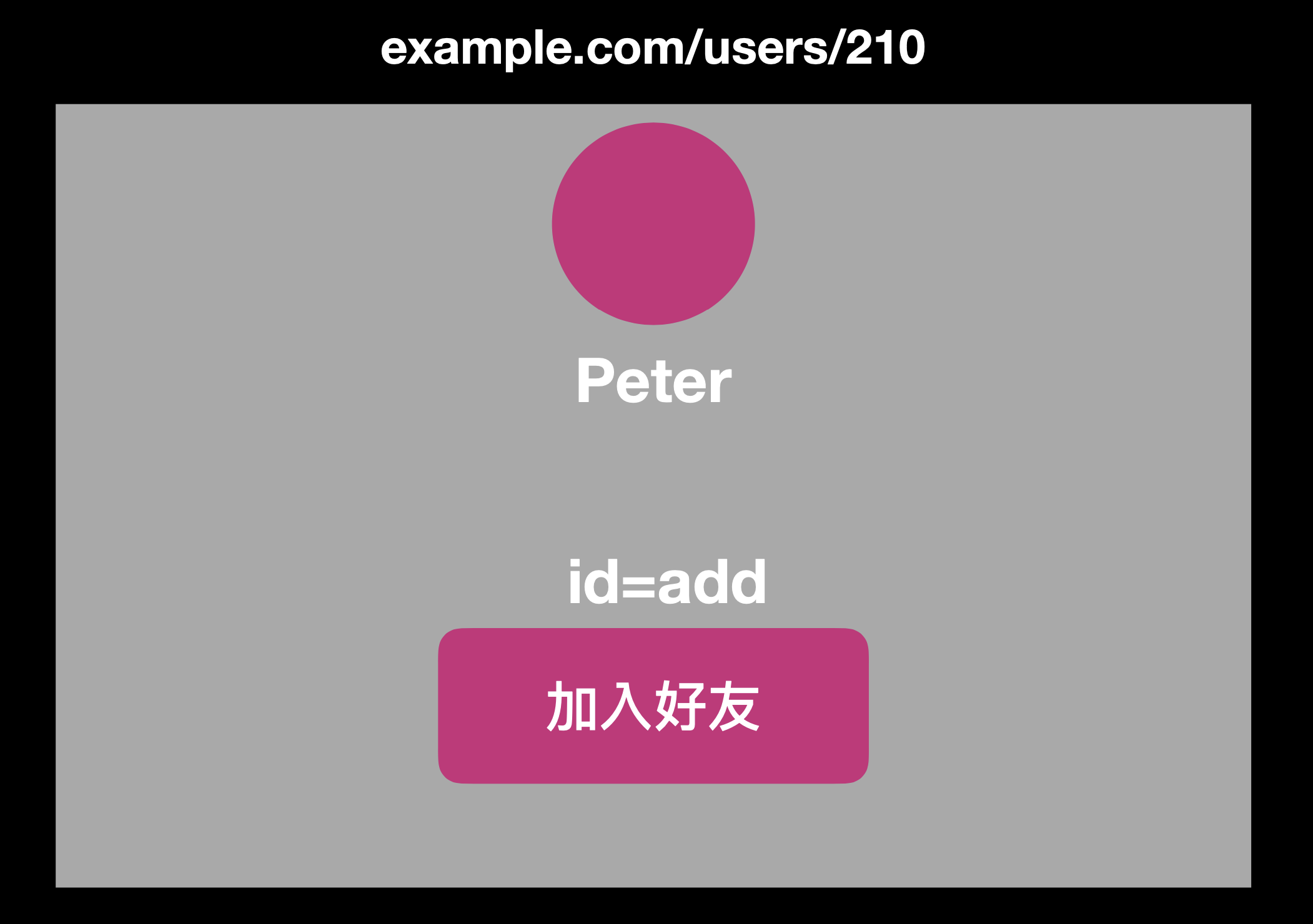

And you and Peter, whose user id is 210, are not friends, so when you click on his page, you will see another button called “Add Friend”, and the id is add:

This sounds reasonable, and the implementation of elements with id on the webpage is perfectly reasonable. However, this also poses a risk of XS leaks.

The browser has a user-friendly feature that you may or may not have noticed. When you add #id to the end of a URL, the browser automatically jumps to the paragraph with that id and focuses on the element (if it can be focused). The anchor function of the article relies on this to jump to a specific paragraph.

Therefore, when I connect to http://example.com/users/123#message, if I am friends with the person with id 123, the “Send Message” button will appear on the page, and the browser will jump to the button and focus on it. What if I am not friends with 123? Then nothing will happen. So we can use this difference to know whether the person with id 123 is a friend of the current user.

The method is similar to the search and download just now. We need to embed the target webpage in an iframe. If this id exists, the iframe will focus, and the original body will blur:

window.onblur = () => {

console.log('是好友')

}

const iframe = document.createElement('iframe')

iframe.src = 'https://example.com/users/123#message'

document.body.appendChild(iframe)Then send this webpage to someone who wants to know their friend status. When they open the webpage, you can know whether they are good friends with 123. If the id of this website is a serial number, you can traverse each id and find out who is in their friend list.

The above are two examples of XS leaks, both achieved through some browser or JS features. If you are interested in these, you can refer to: XS-Leaks Wiki, where there are more interesting cases (these I know are also from this website).

If you want to see actual examples of XS leaks, there are many here: Mass XS-Search using Cache Attack, and this recent one is also interesting: Abusing Slack’s file-sharing functionality to de-anonymise fellow workspace members

Other Features You Might Not Know

In the last paragraph, I want to share some “you might not know” features, or more precisely, features that surprised me when I found out about them. I never thought they could be done.

When setting cookies, there are many parameters that can be set, one of which is called path. For example, if I set the cookie’s path to /siteA, then when I’m on /siteB, I can’t read the cookie from /siteA because the paths are different, so I can’t get it.

But actually, it’s not necessarily true. If your website doesn’t block iframe embedding and the cookie isn’t set to HttpOnly, you can use an iframe to read cookies from different paths:

// 假設我們在 https://example.com/siteA

const iframe = document.createElement('iframe')

iframe.src = 'https://example.com/siteB'

iframe.onload = () =>

alert(iframe.contentWindow.document.cookie)

}

document.body.appendChild(iframe)This is because https://example.com/siteA and https://example.com/siteB are the same origin even though their paths are different. Therefore, you can directly access the document of other same-origin web pages through an iframe and use this feature to get document.cookie.

If iframe is not supported, window.open can achieve the same effect:

const win = window.open('//example.com/siteB')

setTimeout(() => {

alert(win.document.cookie)

}, 1000)However, it should be noted that window.open is blocked by default and requires user permission to open, or the user needs to perform an action to execute it (such as putting the above code in a button onclick).

Later, I found that section 8.5: Weak Confidentiality of RFC 6265 also mentioned this (strange, I didn’t notice it when I read it before):

Cookies do not always provide isolation by path. Although the network-level protocol does not send cookies stored for one path to another, some user agents expose cookies via non-HTTP APIs, such as HTML’s document.cookie API. Because some of these user agents (e.g., web browsers) do not isolate resources received from different paths, a resource retrieved from one path might be able to access cookies stored for another path.

Reading PDF Content

Suppose your website embeds a same-origin PDF file, like this:

<embed src="/test.pdf">How do you use JS to read the content inside this PDF? The answer must be fetch or xhr:

fetch("/test.pdf")

.then(res => res.blob())

.then(res => {

console.log('pdf', res)

})But what if fetch doesn’t work? For example, the server blocks requests from fetch on the backend (using Fetch Metadata). What should you do then? Is there any way to read the content of the PDF?

I used to think it was impossible until I learned about a hidden Chrome API:

/** @override */

handleScriptingMessage(message) {

if (super.handleScriptingMessage(message)) {

return true;

}

if (this.delayScriptingMessage(message)) {

return true;

}

switch (message.data.type.toString()) {

case 'getSelectedText':

this.pluginController_.getSelectedText().then(

this.handleSelectedTextReply.bind(this));

break;

case 'getThumbnail':

const getThumbnailData =

/** @type {GetThumbnailMessageData} */ (message.data);

const page = getThumbnailData.page;

this.pluginController_.requestThumbnail(page).then(

this.sendScriptingMessage.bind(this));

break;

case 'print':

this.pluginController_.print();

break;

case 'selectAll':

this.pluginController_.selectAll();

break;

default:

return false;

}

return true;

}From this code, you can see two commands, selectAll and getSelectedText. The former can select all the content of the PDF, and the latter can get the selected text. Therefore, by combining these two, you can get the text content inside the PDF:

// HTML: <embed id="f" onload="loaded()" src="...">

window.addEventListener('message', e => {

if (e.data.type === 'getSelectedTextReply') {

alert(e.data.selectedText)

}

})

function loaded() {

f.postMessage({type:'selectAll'}, '*')

f.postMessage({type:'getSelectedText'}, '*')

}A simple demo webpage: https://aszx87410.github.io/demo/mw2021/05-pdf/index.html

Although this trick can only be used on text, this hidden feature is really exciting.

Conclusion

To supplement, some of the above attacks may not be applicable to all environments. For example, some attacks require that the website does not block iframes, and cookies used for authentication may not be set to SameSite, otherwise they will be invalid. The method of using name to pass payload may not be applicable in some browsers, but I think this does not affect the interestingness of these attacks.

Some of the bypass techniques mentioned in the article are not written in detail because my focus is on “finding at least one bypass method” rather than “writing all bypass methods”. For more complete bypass techniques, you can refer to: Cheatsheet: XSS that works in 2021.

Many of the techniques mentioned in this article are what I learned through playing CTF, such as XS leaks for downloading files from LINE CTF 2021 - Your Note, reading cookies from different paths from DiceCTF 2021 - Web IDE, and Chrome’s hidden API from zer0pts CTF 2021 - PDF Generator. Through CTF, I saw a different side of the web.

These are some of the front-end related knowledge I have learned recently, each of which has exceeded my imagination. I hope this article can make you feel the same surprise I felt at the beginning and think, “Wow, there are still so many things in front-end that I don’t know.”

Comments