Introduction

There is a very common feature in many websites, which is redirection.

For example, if a page requires permission to view but the user has not logged in yet, the user will be redirected to the login page first, and then redirected back to the original page after logging in.

For instance, suppose there is a social networking site and to view a personal profile, one needs to log in. If Ming’s personal profile URL is https://example.com/profile/ming, then as a visitor, when I click on it, I will be redirected to the login page with the original URL as a parameter:https://example.com/login?redirect=https://example.com/profile/ming

After successful login, the website will redirect me to the original page based on the value of redirect.

Although it seems like a small feature, there are actually many security issues to consider behind it.

What is open redirect?

Open redirect, which is usually translated as “open redirect” or “public redirect” in Chinese, but I prefer to translate it as “arbitrary redirect”, which is closer to the original meaning, means that it can redirect to any destination.

In the example at the beginning of the article, an attacker can actually pass any value on the URL, such as https://attacker.com, so that after the user logs in, they will be redirected to this page.

This is a vulnerability that requires user action (login) to trigger redirection, but some functions may have redirection without user action. In the case of the login example, if the user has already logged in, clicking on the link https://example.com/login?redirect=https://attacker.com will cause the system to detect that the user has already logged in and will directly redirect the user to https://attacker.com.

What is the result of this?

The user clicked on a link from example.com but was unintentionally redirected to attacker.com. This vulnerability that can directly redirect users to any destination is called open redirect.

What problems can open redirect cause?

One of the most obvious attack methods is phishing websites. When talking about attack methods, I think “context” is a pretty important factor. Some seemingly insignificant attacks, when combined with appropriate context, can make you feel “wow, it seems quite easy to succeed.”

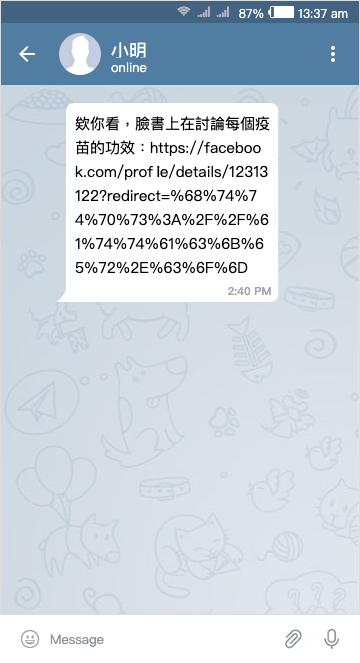

When you can see the URL, you will be more cautious when you see an unfamiliar URL because you know it may be a scam or phishing website. But if you see a familiar URL, you will relax your guard:

The last part of the URL in the picture is actually the result of url encoding https://attacker.com, so the user will not notice the string behind it, only the beginning of the URL starting with facebookb.com. What I want to emphasize here is that “when users see a familiar URL, they will be less vigilant.”

However, in this situation, similar URLs can also achieve similar results (although less effective), such as facebo0k.com or myfacebook.com.

At this point, let’s imagine another scenario where some websites will remind you when you click on an external link: “You are about to go to an external website, be careful.” If you use open redirect at this time, the website may not pop up a warning (because it is the same domain), and the user may unknowingly jump to another website.

For example, suppose there is a forum with an open redirect vulnerability, and I put a link in the article that uses open redirect to disable the prompt for jumping to an external website. When the user clicks the link, they will go to a “well-designed phishing website” that looks exactly the same but pops up a popup asking for the user’s account and password, saying that their connection session has expired and they need to log in again. At this point, the user is more likely to enter their account and password because they did not realize that they were redirected to a phishing website.

All of these issues only discuss the harm that open redirect can cause “without combining with other vulnerabilities”. It seems okay, right? Compared with other attacks, it seems not that serious. However, the underestimated aspect of open redirect is the power it can exert when combined with other vulnerabilities.

Before we continue, we must first understand the implementation of redirection, which is mainly divided into two types:

- Backend redirection, using the response header

Location - Front-end redirection, which may use history.push, window.open, and location, etc.

The first type of redirecting through the backend is done by returning the Location header from the server, and the browser will redirect the user to the corresponding location. The implementation may look like this:

function handler(req, res) {

res.setStatus(302)

res.setHeader('Location: ' + req.query.redirect)

return

}The second type, implemented by the front-end, is different. A common example is to directly assign the destination to window.location for page redirection:

const searchParams = new URLSearchParams(location.search)

window.location = searchParams.get('redirect')Or, if it is an SPA and you don’t want to change pages, you may directly use history.push or the built-in router in the framework.

Regardless of whether it is done by the front-end or the back-end, there are issues that need to be addressed in the implementation of redirection.

Back-end: CRLF injection

In the back-end redirection, the value passed in will be placed in the Location response header. If some servers or frameworks do not handle it properly, newline characters can be inserted. For example, setting the redirected URL to abc\ntest:123 may result in the following response:

HTTP/2 302 Found

Location: abc

test:123If changed to: abc\n\n<script>alert(1)</script>, the response will become:

HTTP/2 302 Found

Location: abc

<script>alert(1)</script>

....By using CRLF injection to change the content of the response body, it is unfortunately impossible to directly achieve XSS because when the browser sees a status code of 301/302, it ignores the response body and directly redirects the user to the target page.

The information I found that can work is already four or five years old:

I remember reading an article about how to deal with this situation, but I couldn’t find it after searching for a long time. If you know how to bypass it, please let me know.

However, even if changing the response body is not very useful, changing other headers may also lead to other attacks, such as Set-Cookie, which can set arbitrary cookies for users, and may lead to session fixation or CSRF attacks.

Front-end: XSS

If the redirection is implemented by the front-end, one issue that needs to be particularly careful is XSS.

You may wonder what the relationship is between redirection and XSS. Let’s first review the code for front-end redirection:

const searchParams = new URLSearchParams(location.search)

window.location = searchParams.get('redirect')What problems does this have?

In JS, there is something that many people have seen but may use less frequently, called the JavaScript pseudo protocol, like this:

<a href="javascript:alert(1)">click me</a>After clicking on that a, it will execute JS to pop up an alert. And this trick can be used not only in href but also on location:

window.location = 'javascript:alert(1)'Open a new tab in your browser and execute the above code directly in the devtool console, and you will find that the alert really pops up, and the following methods will trigger it:

window.location.href = 'javascript:alert(1)'

window.location.assign('javascript:alert(1)')

window.location.replace('javascript:alert(1)')Therefore, as long as the attacker sets the redirect location to javascript:xxx, arbitrary code can be executed, triggering XSS. Front-end developers must pay special attention to this case because assigning the value directly to location is a very common implementation method.

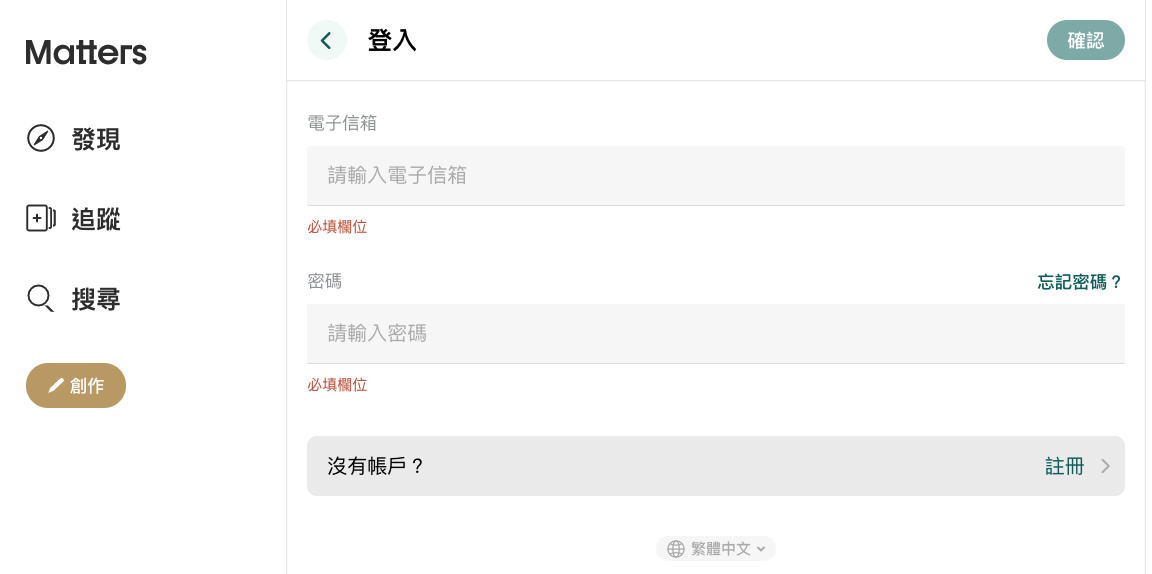

Below is a real-world example, targeting the website that appeared in another article: Preventing XSS May Be Harder Than You Think: Matters News.

This is their login page:

After clicking login, a function called redirectToTarget is called, and the code for this function is as follows:

/**

* Redirect to "?target=" or fallback URL with page reload.

*

* (works on CSR)

*/

export const redirectToTarget = ({

fallback = 'current',

}: {

fallback?: 'homepage' | 'current'

} = {}) => {

const fallbackTarget =

fallback === 'homepage'

? `/` // FIXME: to purge cache

: window.location.href

const target = getTarget() || fallbackTarget

window.location.href = decodeURIComponent(target)

}After obtaining the target, it was directly used as follows: window.location.href = decodeURIComponent(target) for redirection. getTarget is actually used to retrieve the value of target from the URL query string. Therefore, if the login URL is https://matters.news/login?target=javascript:alert(1), an alert will pop up when the user clicks on the login button and successfully logs in, triggering an XSS attack!

Moreover, once this XSS attack is triggered, its impact is significant because it is on the login page. Therefore, the XSS executed on this page can directly capture the input values, which are the user’s account and password. If an actual attack is to be executed, a phishing email can be sent to the website’s users, containing this malicious link for them to click on. Since the URL is a normal one and the page they are redirected to is the actual website’s page, the credibility should be quite high.

After the user enters their account and password and logs in, using XSS to steal the account and password and redirecting the user back to the homepage can steal the user’s account without leaving any traces, achieving account theft.

The fix is to only allow URLs that start with http/https:

const fallbackTarget =

fallback === 'homepage'

? `/` // FIXME: to purge cache

: window.location.href

let target = decodeURIComponent(getTarget())

const isValidTarget = /^((http|https):\/\/)/.test(target)

if (!isValidTarget) {

target = fallbackTarget

}

window.location.href = target || fallbackTargetHowever, this only fixes the XSS vulnerability in the redirection function, and the open redirect vulnerability still exists. Further checks on the domain are required to eliminate the open redirect vulnerability.

Once again, it is worth noting that many engineers may not notice this vulnerability because they do not know that window.location.href can execute code with URLs such as javascript:alert(1). If you have implemented a redirection function, please pay attention to this issue.

Combining Open Redirect with Other Vulnerabilities

From the above two issues, it can be seen that just implementing “redirection” can result in vulnerable code. The following will discuss the combination of the “redirection” function with other vulnerabilities. There are at least two types of vulnerabilities that may be combined with open redirect: SSRF and OAuth vulnerabilities.

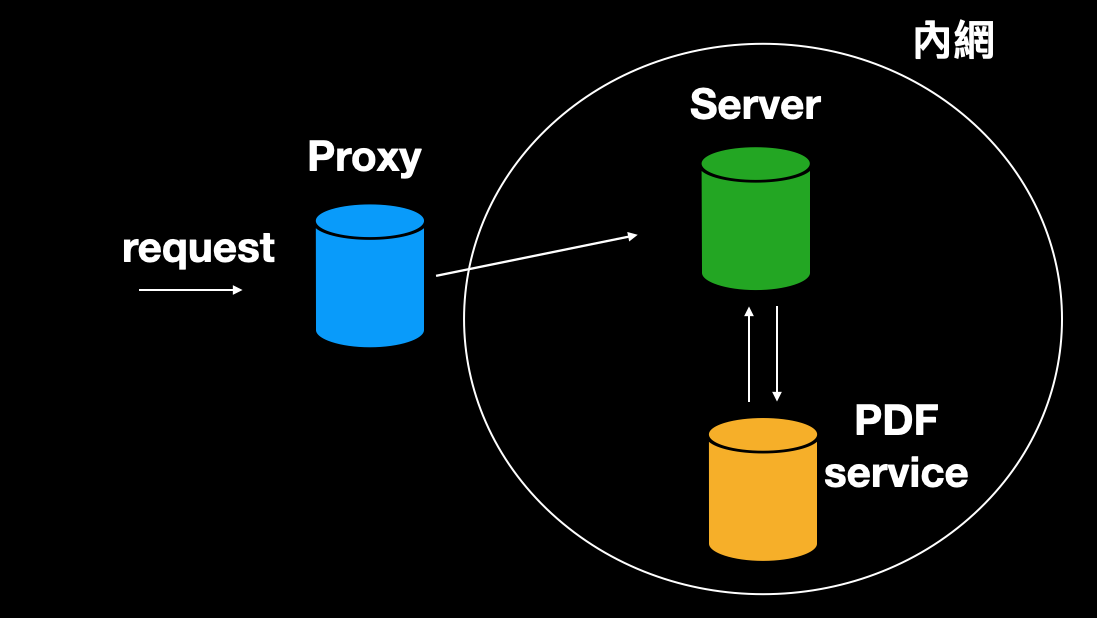

SSRF, or Server-Side Request Forgery, is a vulnerability that allows attackers to forge server requests. A detailed introduction to this vulnerability and future attacks may be written in another article. Here, I will briefly explain it.

Usually, internal servers are not directly accessible from the outside, and there may only be a proxy that forwards requests to the corresponding host. Suppose a service’s server architecture is as shown in the figure below, with a back-end server that calls a PDF service hidden in the intranet to generate a PDF file:

This PDF service restricts URLs to start with https://example.com to prevent anyone from entering other URLs. At this point, if a URL has an open redirect vulnerability, an attacker can enter: https://example.com?redirect=http://127.0.0.1, causing the PDF service to visit this URL, which is redirected to 127.0.0.1 and returns its content.

This is called SSRF, where you successfully send a request to an external service through an internal service. This way, you can see what other services are available on the intranet, such as Redis or MySQL, which cannot be accessed directly from the outside but can be accessed through SSRF. Alternatively, you can simply look at some cloud-related files. Some cloud services only need to access http://169.254.169.254 to see some metadata. If you are interested, you can check this out: Abusing SSRF in AWS EC2 environment.

Therefore, open redirect can bypass the URL check that was originally performed.

The second problem you may encounter is related to OAuth. In the OAuth process, there is usually a redirect_uri, which receives a code after authorization is complete. Taking Facebook as an example, it looks like this:

https://www.facebook.com/v11.0/dialog/oauth?

client_id={app-id}

&redirect_uri={"https://example.com/login"}

&state={"{st=state123abc,ds=123456789}"}After the user clicks on the URL, they will be redirected to Facebook. After clicking on the authorization, they will be redirected to https://example.com/login, where they can obtain the code or token from the URL. Then, they can use this code or token with the client ID and client secret to obtain an auth token and use this auth token to represent the user to obtain data from Facebook.

If the protection of redirect_uri is not done well, attackers can replace it with other values, such as redirect_uri=https://huli.tw. After the user clicks on the authorization, the verification code will be sent to my website instead of the expected website.

However, in general, redirect_uri will restrict the domain, so it is not so easy to bypass. At this time, open redirect comes into play. If the website has this vulnerability, it can be like this: redirect_uri=https://example.com?redirect=https://huli.tw. In this way, even if it meets the domain restriction, the final destination is still an external website, and the attacker can still steal the verification code.

Therefore, to avoid this type of attack, large services such as Facebook or Google will strengthen restrictions when setting up apps. redirect_uri usually requires a fixed setting and does not allow you to set a wildcard. For example, if I fill in https://example.com/auth, only this URL can pass, and other URLs with different paths will fail. However, some small companies have not paid attention to such details, and there are not so many regulations for redirect_uri.

There are actually many examples of combining OAuth with open redirect to achieve account takeover, such as this one: [cs.money] Open Redirect Leads to Account Takeover, or GitHub actually has this type of vulnerability: GitHub Gist - Account takeover via open redirect - $10,000 Bounty, and this Airbnb vulnerability is also very interesting: Authentication bypass on Airbnb via OAuth tokens theft.

To summarize, the purpose of open redirect is not only to allow users to relax their vigilance and engage in phishing, but also to bypass places that check domains. The reason why the SSRF and OAuth vulnerabilities can be combined with it is because open redirect can be used to bypass the domain check.

How to defend against open redirect?

If you want to prevent open redirect, it is obvious that you need to check the redirected URL. This sounds simple, but it is easy to have vulnerabilities in implementation. For example, the following example is a piece of code that checks the domain. According to the extracted hostname, it checks whether it contains cymetrics.io. If it does, it passes. The purpose is that only cymetrics.io and its subdomains can pass:

const validDomain = 'cymetrics.io'

function validateDomain(url) {

const host = new URL(url).hostname // 取出 hostname

return host.includes(validDomain)

}

validateDomain('https://example.com') // false

validateDomain('https://cymetrics.io') // true

validateDomain('https://dev.cymetrics.io') // trueIt seems that there is no problem? Except for cymetrics.io or its subdomains, no other domains should be able to pass this check, right?

Although it seems so, there are actually two ways to bypass it. Here, assuming that there is no problem with URL parsing, hostname will definitely be obtained, so attacker.com?q=cymetrics.io is useless, and the hostname will only be attacker.com.

You can think of two ways to bypass it. Before revealing the answer, let’s take a look at the next paragraph.

Google’s view on open redirect

Google clearly stated on its official website Bughunter University that general open redirect will not be considered a security vulnerability unless it can be proven to be used in combination with other vulnerabilities.

Has anyone succeeded? Of course, I will give two examples.

The first example comes from this article: Vulnerability in Hangouts Chat: from open redirect to code execution, targeting Google Hangouts Chat’s Electron App.

If the URL in that app starts with https://chat.google.com, clicking on the URL will directly open the webpage in Electron instead of using the browser. Therefore, as long as you find the open redirect of https://chat.google.com, you can redirect the user to a phishing website. One of the differences between the Electron app and the browser is that the Electron app does not have an address bar by default, so users have no way to distinguish whether this is a phishing website. The detailed process and the final payload can be found in the original article. This vulnerability can be further upgraded to RCE (but I don’t know how to do it), worth 7500 USD.

The second example comes from an official article: Open redirects that matter, which is also very cool.

There is a feature on the Google I/O 2015 website that retrieves data from Picasa and renders it as JSON. However, due to cross-domain issues, a simple proxy was written on the backend to retrieve the data, like this: /api/v1/photoproxy?url=to. The proxy checks whether the beginning of the URL is https://picasaweb.google.com/data/feed/api. If not, an error is returned.

So the author’s first goal was to find an open redirect on Picasa. The URL he finally found was https://picasaweb.google.com/bye?continue=, and by changing this URL to https://picasaweb.google.com/data/feed/api/../../bye, the server would think it was a legitimate URL and pass the path check.

But it’s not over yet, because the bye?continue= redirect also checks the parameter, and continue must start with https://google.com. Therefore, we need to find the second open redirect, which is on google.com. Google.com has a well-known open redirect used by AMP, such as https://www.google.com/amp/tech-blog.cymetrics.io, which will redirect to https://tech-blog.cymetrics.io (although I just tried it and it will first go to the middle page and then redirect after confirmation, so this feature may have been fixed).

Combining these two open redirects allows the proxy to retrieve the content of the URL we specify:

https://picasaweb.google.com/data/feed/api/../../../bye/?

continue=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2Famp/

your-domain.example.com/path?querystringBut after retrieving it, it will only output as JSON. The backend code is as follows:

func servePhotosProxy(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

c := newContext(r)

if r.Method != "GET" {

writeJSONError(c, w, http.StatusBadRequest, "invalid request method")

return

}

url := r.FormValue("url")

if !strings.HasPrefix(url, "https://picasaweb.google.com/data/feed/api") {

writeJSONError(c, w, http.StatusBadRequest, "url parameter is missing or is an invalid endpoint")

return

}

req, err := http.NewRequest("GET", url, nil)

if err != nil {

writeJSONError(c, w, errStatus(err), err)

return

}

res, err := httpClient(c).Do(req)

if err != nil {

writeJSONError(c, w, errStatus(err), err)

return

}

defer res.Body.Close()

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json;charset=utf-8")

w.WriteHeader(res.StatusCode)

io.Copy(w, res.Body)

}Because the content type is set, MIME sniffing cannot be used to attack. To explain MIME sniffing briefly, when your response does not set the content type, the browser will automatically guess what the content is. If it contains HTML, it will be parsed and rendered as an HTML website.

The author found another bug, which is that if there is an error, the content type is not set, only when it succeeds. Therefore, intentionally returning an error message containing HTML will cause the browser to treat the entire page as HTML when it is printed on the screen, thereby achieving XSS! The detailed process and introduction are written very clearly in the original text, and I highly recommend everyone to read it.

The above are two attacks caused by chaining other vulnerabilities with open redirects that have been discovered in Google. Both are very interesting!

After reading the above, I suddenly became curious about which Google open redirects are well-known, so I googled: known google open redirect and found the following websites:

- How scammers abuse Google Search’s open redirect feature

- Google - Open Redirect

- Google Bug that Makes Your Bank More Vulnerable to Phishing

If it’s just a general https://www.google.com/url?q=http://tech-blog.cymetrics.io, clicking on it will only go to the confirmation page. But if you add a parameter usg at the end, you can be redirected without confirmation. Try clicking on this link, it will go to example.org: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&url=http://example.org/&usg=AOvVaw1YigBkNF7L7D2x2Fl532mA.

So what is this “usg”? It should be the result of a URL that has been hashed in some way, but you won’t know how it was calculated. However, it is not difficult to obtain this “usg”. You can send an email to yourself using Gmail with a link you want to redirect to, and then view it in HTML basic view. You will see that the link in the email has been redirected to the format above!

For example, this is the redirect link for our blog: https://www.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Ftech-blog.cymetrics.io&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AFQjCNHyq6urHn6HLwj8RP09GANAlymZug

After testing, it was found that it can really be redirected without confirmation. This feature seems to have been around for a while, so if you need an open redirect from google.com, you can refer to it.

Check the redirect domain

Okay, let’s go back to the two bypass methods I just asked you about. I will post the code for checking the domain again to let everyone remember, and then I will reveal the answer directly:

const validDomain = 'cymetrics.io'

function validateDomain(url) {

const host = new URL(url).hostname // 取出 hostname

return host.includes(validDomain)

}

validateDomain('https://example.com') // false

validateDomain('https://cymetrics.io') // true

validateDomain('https://dev.cymetrics.io') // trueThis is a common mistake when checking domains, because it does not consider the following two situations:

- cymetrics.io.huli.tw

- fakecymetrics.io

Both of these situations meet the conditions, but they are not the results we want.

In fact, not only when checking domains, it is a more dangerous thing to directly use includes or contains to see if the overall string contains a certain substring when doing any checks. The best way is actually to set an allow list and it must be completely consistent to pass, which is the strictest. But if you want to allow all subdomains, you can check like this:

const validDomain = 'cymetrics.io'

function validateDomain(url) {

const host = new URL(url).hostname // 取出 hostname

return host === validDomain || host.endsWith('.' + validDomain)

}The subdomain part must end with .cymetrics.io, so it will definitely be a subdomain of cymetrics.io, and the main domain must also be completely consistent to pass. However, if you write it like this, if an unrelated subdomain has an open redirect vulnerability, this section will fail. Therefore, it is still recommended that you only put the domains that are confirmed to be redirected into the list and directly use === for checking to avoid this situation.

Conclusion

Redirecting is a very common function, the most common of which is to click on a link before logging in and then redirecting to the login page. After successful login, it will automatically redirect back. When doing this function, if it is a front-end redirect, I would like to remind everyone again to consider that window.location = 'javascript:alert(1)' will cause problems, so please make sure that the redirected URL is a legal URL before taking action. In addition, it is also necessary to ensure that when checking the domain, possible bypass situations are considered, and the most rigorous method is used as much as possible to handle it.

The above is an introduction to open redirect. I hope it is helpful to everyone. If you have any questions or mistakes, you can discuss them with me in the comments below.

References:

Comments