Introduction

Among various attack methods targeting front-end, I find clickjacking quite interesting. Its Chinese translation is usually “click hijacking”, which actually means that you think you clicked something on website A, but in fact, you clicked on website B. Malicious websites hijack users’ clicks, making them click on unexpected places.

Just a click, what harm can it cause?

Suppose it is a bank transfer page in the background, and the account number and amount are filled in. Just press a button and the money will be transferred out. This is very dangerous (but usually unlikely, because transferring money still requires entering OTP and the like, this is just an example).

Or take a more common example. There is a page that looks like a page for unsubscribing from an email newsletter, so you click the “Confirm Unsubscribe” button, but actually, there is a Facebook Like button hidden underneath, so you not only did not unsubscribe, but also gave a Like (because the target of hijacking is Like, it is also called likejacking).

In this article, I will introduce the attack principle, defense methods, and practical cases of clickjacking, so that everyone can better understand this attack method.

Clickjacking Attack Principle

The principle of clickjacking is to stack two web pages together, and use CSS to make the user see website A, but click on website B.

In more technical terms, it is to embed website B using iframe and set the transparency to 0.001, and then use CSS to stack its own content on top of it, and it’s done.

I think the most interesting way to understand clickjacking is to look at examples, so I made some simple examples.

In the following example, you can click the “Confirm Unsubscribe” button first, and then click “Switch Transparency” to see that the background is actually a page for modifying personal information and deleting the account button:

So I thought I clicked “Confirm Unsubscribe”, but in fact, I clicked “Delete Account”, this is clickjacking.

If the above iframe cannot be opened, you can play here: clickjacking example.

Some people may think that this example is too simple, and in actual applications, such simple attacks may rarely occur. Maybe more websites will be a little more complicated, such as requiring input of something first?

In the following example, “Change Email” function is designed for clickjacking. Compared with the previous example where the entire webpage is covered, this example deliberately leaves the input of the original webpage, and covers everything else with CSS. The button part uses pointer-events:none to let the event penetrate.

It seems to be a webpage for entering email subscription information, but after clicking OK, it pops up “Email modification successful”, because the background is actually a webpage for modifying email:

If you didn’t see the above example, you can play here: Advanced clickjacking example.

In addition, I also saw a very interesting example in The latest cross-browser exploit-Clickjacking: Fake game, real hijacking (YouTube video), which seems to be a game but actually just wants you to click the button, super interesting!

To summarize clickjacking, the attack method is roughly:

- Embed the target webpage into the malicious webpage (through iframe or other similar tags)

- Use CSS on the malicious webpage to cover the target webpage, making it invisible to the user

- Induce the user to go to the malicious webpage and make an operation (input or click, etc.)

- Trigger the behavior of the target webpage to achieve the attack

Therefore, the difficulty of the actual attack depends on how well your malicious website is designed and how much interaction the target webpage requires. For example, clicking a button is much easier than entering information.

Also, it should be reminded that to achieve this kind of attack, the user must be logged in to the target website first. As long as the target webpage can be embedded in the malicious webpage, there will be a risk of clickjacking.

Clickjacking Defense Methods

As mentioned earlier, any webpage that can be embedded in another webpage is at risk of clickjacking. In other words, if a webpage cannot be embedded, there will be no clickjacking issue. This is the way to solve clickjacking.

Generally, there are two ways to defend against clickjacking. One is to use JavaScript to check, and the other is to inform the browser whether the webpage can be embedded through the response header.

Frame busting

There is a method called frame busting, which is the JavaScript check I mentioned earlier. The principle is very simple, and the code is also very simple:

if (top !== self) {

top.location = self.location

}Each webpage has its own window object, and window.self points to its own window. top refers to the top window, which can be thought of as the top-level window of the entire browser “tab.”

If a webpage is opened independently, top and self will point to the same window. However, if the webpage is embedded in an iframe, top will refer to the window that uses the iframe.

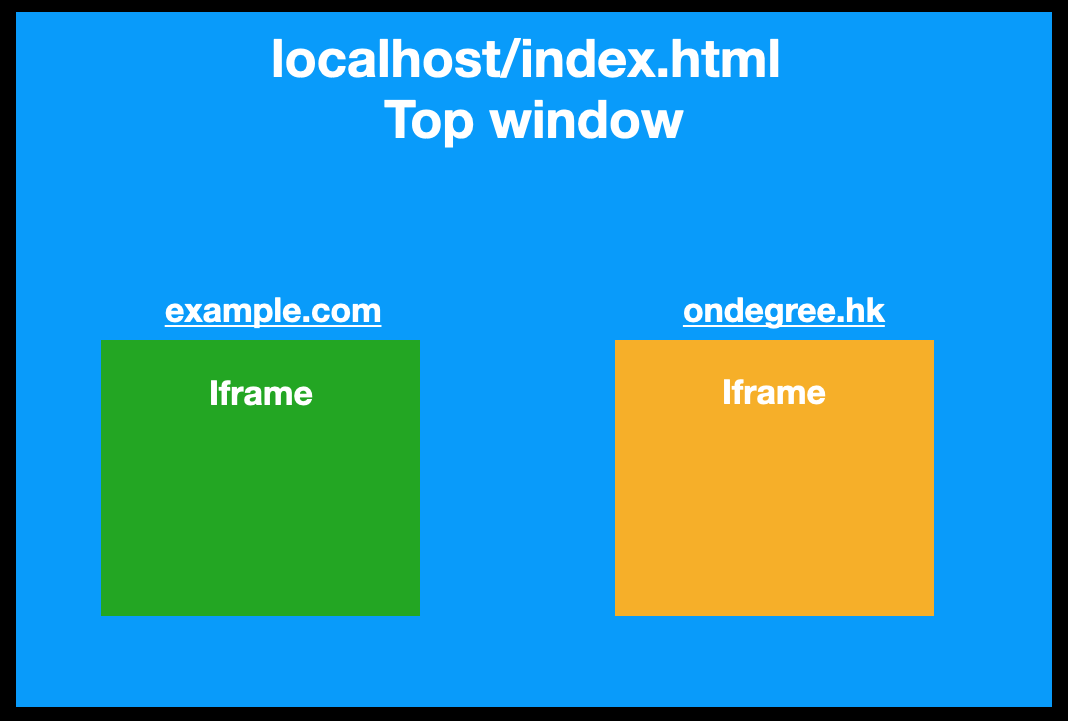

For example, suppose I have an index.html on localhost that contains:

<iframe src="https://example.com"></iframe>

<iframe src="https://onedegree.hk"></iframe>Then the relationship diagram will be like this:

The green and yellow colors are two webpages loaded in iframes, which are two different windows. If you access top in these two webpages, it will be the window object of localhost/index.html.

Therefore, by checking if (top !== self), you can know whether you are in an iframe. If so, change top.location to redirect the top-level webpage to another location.

It sounds good and there doesn’t seem to be any problems, but it can actually be bypassed by the sandbox attribute of the iframe.

An iframe can set an attribute called sandbox, which means that the functionality of the iframe is restricted. If the restrictions need to be lifted, they must be explicitly specified. The values that can be specified include:

- allow-forms, allowing form submission

- allow-scripts, allowing JS execution

- allow-top-navigation, allowing changes to top location

- allow-popups, allowing pop-ups

(There are many more, please refer to MDN: iframe for details.)

That is to say, if I load the iframe like this:

<iframe src="./busting.html" sandbox="allow-forms allow-scripts">Even if busting.html has the protection I mentioned above, it will not work because JavaScript will not execute, so that script will not run. However, the user can still submit the form normally.

So someone proposed a more practical method, which is to make some improvements on the existing basis (code taken from: Wikipedia - Framekiller):

<style>html{display:none;}</style>

<script>

if (self == top) {

document.documentElement.style.display = 'block';

} else {

top.location = self.location;

}

</script>First, hide the entire webpage. JavaScript must be executed to open it, so if the sandbox is used to prevent script execution, only a blank webpage will be seen. If the sandbox is not used, the JS check will not pass, so a blank page will still be seen.

Although this can achieve more complete defense, there are also drawbacks. The drawback is that if the user turns off the JS function, they will not see anything. Therefore, for users who turn off the JS function, the experience is not very good.

When clickjacking first came out (in 2008), the relevant defense may not have been so complete, so these methods had to be used. However, in 2021, browsers have supported better ways to block webpages from being embedded.

X-Frame-Options

This HTTP response header was first implemented by IE8 in 2009, and other browsers followed suit. It became a complete RFC7034 in 2013.

This header has the following three values:

- X-Frame-Options: DENY

- X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

- X-Frame-Options: ALLOW-FROM https://example.com/

The first one is to reject any webpage from embedding this webpage, including <iframe>, <frame>, <object>, <applet>, and <embed> tags.

The second one only allows same-origin webpages, while the last one only allows specific origins to be embedded. Other than that, nothing else is allowed (only one value can be put, not a list, so if you want multiple origins, you need to adjust the output dynamically on the server like the CORS header).

RFC also specifically mentions that the judgment of the last two methods may be different from what you think, and the implementation of each browser may vary.

For example, some browsers may only check the “previous layer” and the “top layer” instead of checking every layer. What does “layer” mean? Because theoretically, an iframe can have an infinite number of layers, A embeds B embeds C embeds D…

If this relationship is visualized as an HTML tag, it would look like this:

<example.com/A.html>

<attacker.com>

<example.com/B.html>

<example.com/target.html>For the innermost target.html, if the browser only checks the previous layer (B.html) and the top layer (A.html), then even if it is set to X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN, the check will still pass because these two layers are indeed the same origin. However, in reality, there is a malicious webpage sandwiched in between, so there is still a risk of being attacked.

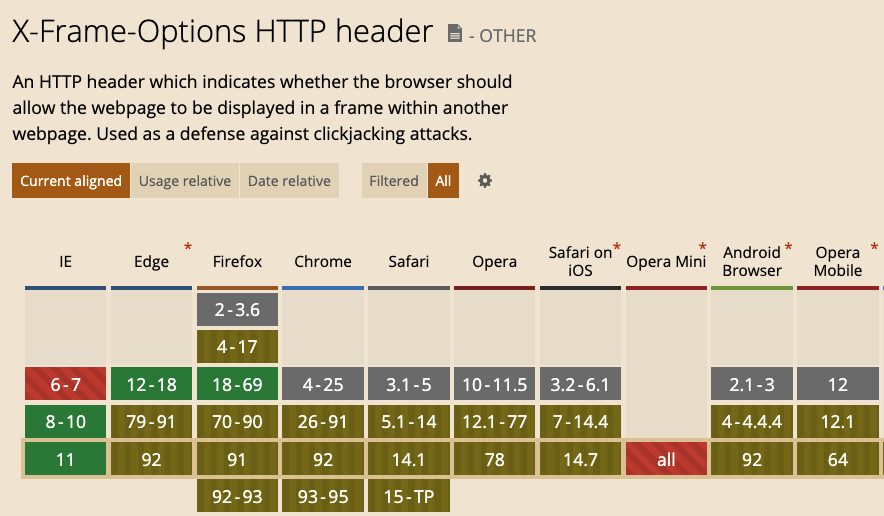

In addition, X-Frame-Options has a second problem, which is that the support for ALLOW-FROM is not good. You can refer to the table below from caniuse, where the yellow ones do not support ALLOW-FROM:

The X at the beginning of X-Frame-Options indicates that it is more like a transitional thing, and its function will be replaced by CSP (Content Security Policy) in future new browsers, and the above-mentioned problems will be solved.

CSP: frame-ancestors

In a previous article: A Brief Discussion on the Various Links in XSS Attacks and Defenses, I briefly mentioned CSP, which is basically telling the browser some security-related settings, one of which is frame-ancestors, which is set up like this:

- Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors ‘none’

- Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors ‘self’

- Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors https://a.example.com https://b.example.com

These three correspond exactly to the three types of X-Frame-Options mentioned earlier: DENY, SAMEORIGIN, and ALLOW-FROM (but this time multiple origins are supported).

First, let’s talk about a place that may be confusing. The behavior restricted by frame-ancestors is the same as X-Frame-Options, which is “which webpages can embed me using iframe”, while another CSP rule frame-src is: “which sources of iframe can my webpage load”.

For example, if I set a rule in index.html as frame-src: 'none', then any webpage loaded with <iframe> in index.html will be blocked, regardless of whether that webpage has set anything.

Another example, if I set my index.html to frame-src: https://example.com, but example.com also sets frame-ancestors: 'none', then index.html still cannot load example.com with iframe because the other party refused.

In summary, frame-src is “are we getting along?”, while frame-ancestors is the answer to this request. I can set it to frame-ancestors: 'none', which means I don’t want anyone to confess to me. Both parties must agree for the browser to successfully display the iframe.

Also, it is worth noting that frame-ancestors is a rule supported by CSP level2, and it gradually began to be supported by mainstream browsers at the end of 2014.

Defense Summary

Due to compatibility issues, it is recommended to use X-Frame-Options and CSP’s frame-ancestors together. If you don’t want your webpage to be loaded in an iframe, remember to add the HTTP response header:

X-Frame-Options: DENY

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors 'none'If you only allow loading from the same origin, set it to:

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors 'self'If you want to specify an allow list of sources, it is:

X-Frame-Options: ALLOW-FROM https://example.com/

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors https://example.com/Actual Cases

Next, let’s take a look at some actual clickjacking cases, which will give you a better sense of this attack.

Yelp

The largest restaurant review website in the United States, Yelp, has several reports on clickjacking:

- ClickJacking on IMPORTANT Functions of Yelp

- CRITICAL-CLICKJACKING at Yelp Reservations Resulting in exposure of victim Private Data (Email info) + Victim Credit Card MissUse.

Although it cannot achieve serious attacks such as account theft, it can still cause some harm, such as stealing users’ emails by helping them make reservations, or causing financial losses by charging cancellation fees when users cancel reservations.

For restaurants that are disliked, this method can also be used to create many fake reservations, making it difficult for restaurants to distinguish (because they are all real users making reservations).

Twitter Periscope Clickjacking Vulnerability

Original report: https://hackerone.com/reports/591432

Date: May 2019

This bug is due to compatibility issues. The webpage only sets X-Frame-Options ALLOW-FROM without setting CSP. This is actually useless because modern browsers do not support ALLOW-FROM.

The solution is simple, just add CSP’s frame-ancestors to make modern browsers also follow this rule.

Highly wormable clickjacking in player card

Original report: https://hackerone.com/reports/85624

Date: August 2015

This vulnerability is quite interesting and uses the browser implementation issues mentioned earlier. In this case, Twitter has already set X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN and Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors 'self', but at that time, some browser implementations only checked whether the top window met the conditions.

In other words, if it is twitter.com => attacker.com => twitter.com, it will pass the check, so it can still be embedded in a malicious webpage.

In addition, this vulnerability occurred in Twitter’s timeline, so it can achieve the effect of a worm. After clickjacking, it will tweet, and then more people will see it and tweet the same thing.

The author’s writeup is great, but the blog is down, this is the archive: Google YOLO

[api.tumblr.com] Exploiting clickjacking vulnerability to trigger self DOM-based XSS

Original report: https://hackerone.com/reports/953579

Date: August 2020

I specifically chose this case because it is a chain of attacks!

In XSS vulnerabilities, there is a type called self XSS, which means that usually users have to perform some operations themselves to be attacked, so the impact is very limited, and many programs do not accept self XSS vulnerabilities.

And this report links self XSS with clickjacking, allowing users to trigger self XSS through clickjacking, making the attack chain easier to achieve and more feasible.

The above are some practical examples related to clickjacking. It is worth noting that some of them are issues caused by compatibility issues, not lack of settings, so setting correctly is also important.

Unpreventable clickjacking?

The way to defend against clickjacking is to not let others embed your webpage, but what if the purpose of this webpage is to let others embed it?

For example, the Facebook widget, the “like” and “share” buttons that we often see, are designed to be embedded by others using iframes. What should be done with this type of widget?

According to these two articles:

- Clickjacking Attack on Facebook: How a Tiny Attribute Can Save the Corporation

- Facebook like button click

The information obtained inside may only reduce user experience a little in exchange for security. For example, after clicking the button, a popup will still appear for you to confirm. For users, there is one more click, but it also avoids the risk of likejacking.

Or I guess it may also decide whether to have this behavior based on the source of the website. For example, on some more reputable websites, this popup may not appear.

I have made a simple demo webpage: https://aszx87410.github.io/demo/clickjacking/like.html

If likejacking is successful, clicking the button will like the Facebook Developer Plugin fan page (I have successfully experimented with it myself). Everyone can try it out and click “Show original webpage” to see what the button looks like underneath, and also retract the like.

Summary

Compared to the era when browser support was not so complete in the past, we are now much happier. Browsers have also implemented more and more security features and new response headers to protect users from malicious attacks.

Although the difficulty, prerequisites, and impact of clickjacking attacks are usually lower than attacks such as XSS or CSRF on average, it is still one of the risks that cannot be ignored.

If your webpage does not allow other websites to be embedded, remember to set X-Frame-Options: DENY and Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors 'none' to tell the browser that your webpage cannot be embedded, thereby preventing clickjacking attacks.

References:

Comments