Preface

Recently, I was researching some things related to HTTP Cache, and I found myself confused by the different headers such as Pragma, Cache-Control, Etag, Last-Modified, Expires, etc. After reading many reference materials, I gained a deeper understanding. I thought that if I could understand Cache from a different perspective, it might be easier to understand what these headers are doing.

In the previous research materials, many articles explained the functions and parameters of each header one by one. However, I think that too many parameters can easily confuse beginners. Therefore, this article attempts to guide the usage scenarios and purposes of each header step by step through different questions. Also, because this article is for beginners, not all parameters will be discussed.

In fact, there are different opinions on Cache on the Internet. If there are any doubts, I will try to follow the standards written in the RFC. If there are any errors, please correct me. Thank you.

Why do we need Cache?

Asking “why” is a good habit. Before using something, you must know why you need it. So, we need to ask ourselves a question: Why do we need Cache?

It’s simple, because it saves traffic, time, or more macroscopically, reduces resource consumption.

For example, the homepage of an e-commerce website may have many products. If you retrieve all the data from the database every time a visitor visits the homepage, it will be a huge burden on the database.

However, in fact, these information on the homepage will not change in the short term. The price of a product cannot be one thousand yuan one second and two thousand yuan the next second. Therefore, these infrequently changing data are suitable for storage, which is what we call Cache.

In the above example, the information on the homepage can be retrieved once and stored somewhere, such as Redis, which is actually stored in the form of a simple Key-Value Pair. Then, whenever this information is used, it can be retrieved at an extremely fast speed, instead of recalculating it in the database.

The above is Server-side Cache, which is achieved by retrieving data from the database and storing it elsewhere. However, Server-side Cache is not the focus of today. Interested readers can refer to my previous article: Redis Introduction.

Today’s focus is on the Cache mechanism between the Server and the browser.

For example, the product images on an e-commerce website. If there is no Cache, the hundreds of product images displayed on the homepage will be downloaded several times as the webpage is viewed several times, which is a huge amount of traffic. Therefore, we must allow the browser to Cache these images. This way, only the first time the webpage is viewed will it need to be downloaded again. The second time it is viewed, the images can be retrieved directly from the browser’s Cache, without requesting data from the Server.

Expires

To achieve the above function, you can add an Expires field in the HTTP Response Header, which is the expiration time of this Cache, for example:

Expires: Wed, 21 Oct 2017 07:28:00 GMTAfter the browser receives this Response, it will Cache this resource. When the user visits this page again or requests the resource of this image, the browser will check whether the “current time” has exceeded this Expires. If it has not exceeded, the browser “will not send any Request”, but will directly retrieve the data from the Cache stored on the computer.

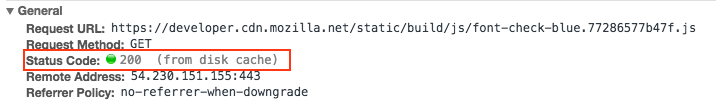

If you open the Chrome dev tool, you will see that it says: “Status code 200 (from disk cache)”, which means that this Request did not actually go out, and the Response was directly retrieved from the disk cache.

However, this will actually encounter a problem, because the browser checks the expiration time of this Expires using the “computer’s own time”. What if I like to live in the future and change the time of my computer to 2100?

The browser will think that all Cache has expired and will send the Request again.

Cache-Control and max-age

Expires is actually a Header that existed in HTTP 1.0. In order to solve the problem encountered by Expires above, a new header appeared in HTTP 1.1, called Cache-Control. (Note: Cache-Control is a Header that appeared in HTTP 1.1, but it not only solves this problem, but also solves many Cache-related problems that HTTP 1.0 cannot handle.)

One usage is: Cache-Control: max-age=30, which means that the expiration time of this response is 30 seconds. If the user refreshes the page after 10 seconds of receiving this response, the phenomenon of being cached by the browser will appear as shown above.

But if the user refreshes the page after 60 seconds, the browser will send a new request.

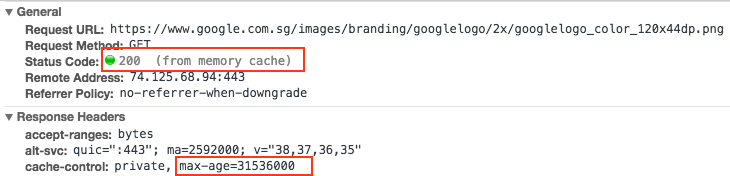

If you carefully observe the response header of the Google Logo file, you will find that its max-age is set to 31536000 seconds, which means 365 days. As long as you visit this website within a year, no request will be sent for the Google logo image, and the browser will directly use the cached response, which is Status code 200 (from memory cache) written here.

Now we encounter a problem. Since both Expires and max-age can determine whether a response has expired, which one should the browser look at if both appear?

According to the definition of RFC2616:

If a response includes both an Expires header and a max-age directive, the max-age directive overrides the Expires header, even if the Expires header is more restrictive.

max-age overrides Expires. Therefore, although both are placed in the cache, only max-age is actually used.

Expired, then what?

Both of these headers are concerned with the “freshness” of a response. If the response is fresh enough (that is, it has not exceeded Expire or is within the period specified by max-age), the data is directly retrieved from the cache. If it has expired or is not fresh, a request is sent to the server to obtain new data.

But here is a special point to note: “Expired does not mean unusable.”

What does this mean? It was mentioned earlier that Google’s Logo cache time is one year, and the browser will send a new request after one year, right? But it is very likely that Google’s Logo will not change even after a year, which means that the image cached by the browser can still be used.

If this is the case, the server does not need to return a new image, just tell the browser: “You can continue to use the cached image for another year.”

Last-Modified and If-Modified-Since

To achieve the above function, both the server and the client must cooperate with each other. One way is to use the combination of Last-Modified and If-Modified-Since, which HTTP 1.0 already has.

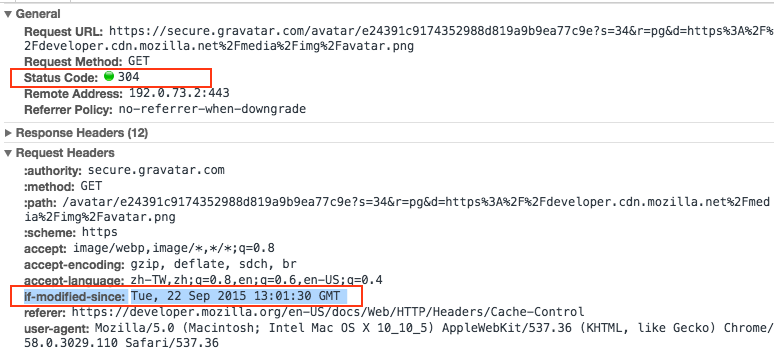

When the server sends a response, it can add a Last-Modified header to indicate when the file was last modified. When the cache expires, the browser can use this information to use If-Modified-Since to specify the data that has been changed since a certain point in time when making a request to the server.

Let’s take an example. Suppose I request the Google homepage image and receive the following response (for readability, the date format has been changed, and the actual content will not be like this):

Last-Modified: 2017-01-01 13:00:00

Cache-Control: max-age=31536000After receiving this response, the browser will cache this image and mark the last update time of this file as 2017-01-01 13:00:00, and the expiration time is one year.

If I request this image again after half a year, the browser will tell me: “You don’t need to request it again. The expiration time of this file is one year, and only half a year has passed. Do you want the data? I have it here!” So no request will be sent, and the data will be obtained directly from the browser.

Then, after one year, I request this image again, and the browser will say: “Hmm, my cache has indeed expired. I will ask the server if the file has been updated since 2017-01-01 13:00:00.” It will send the following request:

GET /logo.png

If-Modified-Since: 2017-01-01 13:00:00If the file has indeed been updated, the browser will receive a new file. If the new file has the same cache headers, it will be cached in the same way as before. What if the file has not been updated?

Assuming there are no updates, the server will return a Status code: 304 (Not Modified), indicating that you can continue to use the cached file.

Etag and If-None-Match

Although the above method seems to be good enough, there is still a small problem.

The above mentioned whether the file has been “edited”, but in fact, this editing time is the editing time of the file on your computer. If you open the file, do nothing, and then save it, this editing time will also be updated. However, even if the editing time is different, the content of the file is still exactly the same.

Compared with the editing time, if “whether the file content has changed” can be used as the condition for updating the cache, it would be even better.

And the Etag header is such a thing. You can think of Etag as the hash value of the content of this file (but it is not, but the principle is similar, in short, the same content will generate the same hash, and different content will generate different hash).

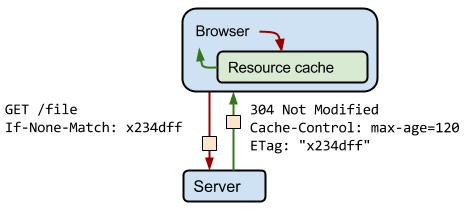

In the Response, the server will bring the Etag of this file. After the cache expires, the browser can use this Etag to ask if the file has been changed.

Etag and If-None-Match are also a pair used together, just like Last-Modified and If-Modified-Since.

When returning the Response, the server brings the Etag to indicate the unique hash of this file. After the cache expires, the browser sends If-None-Match to ask the server if there is new data (data that does not match this Etag). If there is, it will return the new data. If not, it will only return 304.

The process can refer to the following figure on the Google website:

(source: https://web.dev/articles/http-cache )

Intermission

Let’s summarize what we have learned so far:

ExpiresandCache-Control: max-agedetermine the “freshness” of this cache, that is, when it will “expire”. Before it expires, the browser “will not” send any Request.- When the cache expires,

If-Modified-SinceorIf-None-Matchcan be used to ask the server if there is new data. If there is, it will return the new data. If not, it will return Status code 304, indicating that the resources in the cache can still be used.

With these headers, the world seems beautiful, as if all problems have been solved.

Yes, I said “seems”, which means that there are still some problems.

What if you don’t want to cache?

Some pages may not want any caching, such as pages containing some confidential information, and do not want anything to be retained on the client side.

Remember that we mentioned at the beginning that the Cache-Control header actually solves more problems? In addition to specifying max-age, you can directly use: Cache-Control: no-store, which means: “I don’t want any caching”.

Therefore, every request will definitely reach the server to request new data, and no information will be cached.

(Note: In HTTP 1.0, there is a Pragma header, which has only one usage, that is: Pragma: no-cache. Some information on the Internet says that it means no caching, but according to RFC7232, this usage should be the same as Cache-Control: no-cache, not Cache-Control: no-store. The difference between these two will be mentioned later.)

Cache strategy for the homepage

The above mentioned are some static resources such as pictures, which will not change for a while, so you can safely use max-age.

But now we are considering another situation, that is, the homepage of the website.

Although the homepage of the website will not change frequently, we hope that users can see the changes immediately once they change. What should we do? Set max-age? It is also possible, for example, Cache-Control: max-age=30, which allows the cache to expire after 30 seconds and go to the server to get new data.

But what if we want it to be more real-time? Once it changes, users can see the changes immediately. You may say, “Then we can just not cache it, and fetch new pages every time.” But if this homepage has not changed for a week, using caching is actually a better way to save a lot of traffic.

So our goal is: “Cache the page, but as soon as the homepage changes, we can immediately see the new page.”

How do we achieve this? First, you can use Cache-Control: max-age=0, which means that this response will expire after 0 seconds, meaning that as soon as the browser receives it, it will be marked as expired. This way, when the user visits the page again, it will ask the server if there is any new data, and with the use of Etag, it can ensure that only the latest response is downloaded.

For example, the first response may be like this:

Cache-Control: max-age=0

Etag: 1234When I refresh it, the browser sends this request:

If-None-Match: 1234If the file has not changed, the server will return 304 Modified, and if it has changed, it will return the new file and update the Etag. If you use this method, it is actually “sending a request to confirm whether there is a new file every time you visit the page. If there is, download the update, otherwise use the cache.”

In addition to the above trick max-age=0, there is actually a standardized strategy called: Cache-Control: no-cache. no-cache does not mean “do not use the cache at all”, but is the same as the behavior described above. It will send a request every time to confirm if there is a new file.

(Note: There are actually subtle differences between these two, see What’s the difference between Cache-Control: max-age=0 and no-cache?)

If you want to “not use the cache at all”, it is Cache-Control: no-store. Don’t get confused here.

To avoid confusion, let me explain the difference between these two again:

Assuming that website A uses Cache-Control: no-store and website B uses Cache-Control: no-cache.

When you revisit the same page every time, whether A website has been updated or not, A website will always send the “entire new file”. Assuming that index.html is 100 kb, and you visit it ten times, the accumulated traffic will be 1000kb.

For website B, let’s assume that the website has not been updated for the first nine visits, and it is only updated on the tenth visit. So the server will only return Status code 304 for the first nine times, and let’s assume that the size of this packet is 1kb. The tenth time, because there is a new file, it will be 100kb. The total traffic for ten times is 9 + 100 = 109 kb.

It can be seen that the effects achieved by A and B are the same, that is, “as long as the website is updated, users can immediately see the results”, but the traffic of B is much lower than that of A because it makes good use of caching strategies. You only need to confirm whether the website has been updated every time you request, and you don’t need to download the entire file every time.

This is the difference between no-store and no-cache, never use the cache and always check the cache.

The last question

Nowadays, Web Apps are popular, and many websites use the SPA architecture with Webpack packaging. The front-end only needs to import a JavaScript file, and rendering is done by JavaScript.

For this type of website, the HTML may look like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link rel='stylesheet' href='style.css'></link>

<script src='script.js'></script>

</head>

<body>

<!-- body is empty, all content is rendered by js -->

</body>

</html>After the JavaScript is loaded, it uses JavaScript to render the page.

In the face of this situation, we hope that this file can be like the homepage file above, “as long as the file is updated, users can immediately see the new results”, so we can use Cache-Control: no-cache to achieve this goal.

But, do you remember that no-cache actually means that every time you visit the page, you will ask the server if there are any new results? This means that a request will be sent no matter what.

Is it possible not to even send a request?

This means: “As long as the file is not updated, the browser will not send a request and will directly use the cache. As soon as the file is updated, the browser will immediately fetch the new file.”

The former is actually what max-age does, but max-age cannot judge whether the file has been updated.

So actually, this goal cannot be achieved solely by relying on the browser’s caching mechanism we introduced earlier. It requires cooperation from the server side. In fact, it is to implement the Etag mechanism in the file itself.

What does that mean? Let’s take a look at an example. We change index.html to this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link rel='stylesheet' href='style.css'></link>

<script src='script-qd3j2orjoa.js'></script>

</head>

<body>

<!-- body is empty, all content is rendered by js -->

</body>

</html>Note that the JavaScript file name has become: script-qd3j2orjoa.js, which is actually the hash value representing this file, just like Etag. Then we set the cache strategy of this file to: Cache-Control: max-age=31536000.

This way, this file will be cached for one year. No new request will be sent to this URL within a year.

What if we want to update it? We don’t update this file directly, but update index.html and change the JavaScript file to:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link rel='stylesheet' href='style.css'></link>

<script src='script-8953jief32.js'></script>

</head>

<body>

<!-- body is empty, all content is rendered by js -->

</body>

</html>Because the cache strategy of index.html is no-cache, every time you visit this page, it will check whether index.html has been updated.

In this example, it has indeed been updated, so the new one will be returned to the browser. The browser will download and cache the new JavaScript file.

By implementing the Etag mechanism in index.html, we have achieved our goal: “As long as the file is not updated, the browser will not send a request and will directly use the cache. As long as the file is updated, the browser will immediately fetch the new file.”

The principle is to adopt different caching strategies for different files and force the browser to re-download by “replacing the JavaScript file”.

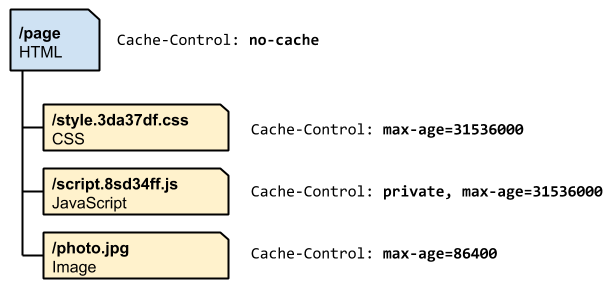

You can also refer to the picture provided by Google:

(source: https://web.dev/articles/http-cache )

Conclusion

The reason why the caching mechanism is a bit complicated is because it is divided into different parts, and each related header is actually responsible for different parts. For example, Expires and max-age are responsible for checking whether the cache is “fresh”, while Last-Modified, If-Modified-Since, Etag, and If-None-Match are responsible for asking whether the cache can “continue to be used”. no-cache and no-store represent whether to use the cache and how to use it.

This article only talks about half of the caching mechanism. The parts that are not mentioned are mostly related to shared cache and proxy servers. Are there other values that determine whether the cache can be stored on the proxy server? Or should the verification of whether it can continue to be used be verified with the original server or the proxy server? Readers who are interested in knowing more can refer to the reference materials below.

Finally, I hope this article can help beginners better understand the HTTP caching mechanism.

Reference materials

- Thoroughly understand the Http caching mechanism-based on the decomposition method of the three elements of caching strategy

- A brief discussion on the browser’s http caching mechanism

- 【Web caching mechanism series】1-Overview of Web caching

- HTTP caching control summary

- MDN - Cache-Control

- rfc2616

- Google Web Fundamentals

- HTTP 1.0 spec

Comments