I have written some articles about XSS before, mainly discussing the implementation of prevention and defense details:

- Preventing XSS may be harder than you think

- A brief discussion on the various aspects of XSS attacks and defense

Originally, I wanted to write about the basics of XSS, the three types that everyone has heard of: Stored (Persistent), Reflected (Non-Persistent), and DOM-based XSS. However, when I was about to start writing, I suddenly had a few questions in my mind: “When did XSS appear? When were these three types classified?”

Therefore, I spent some time looking for information, and this article will talk about the history of XSS with you, so that we can better understand the past and present of XSS.

The Birth of XSS

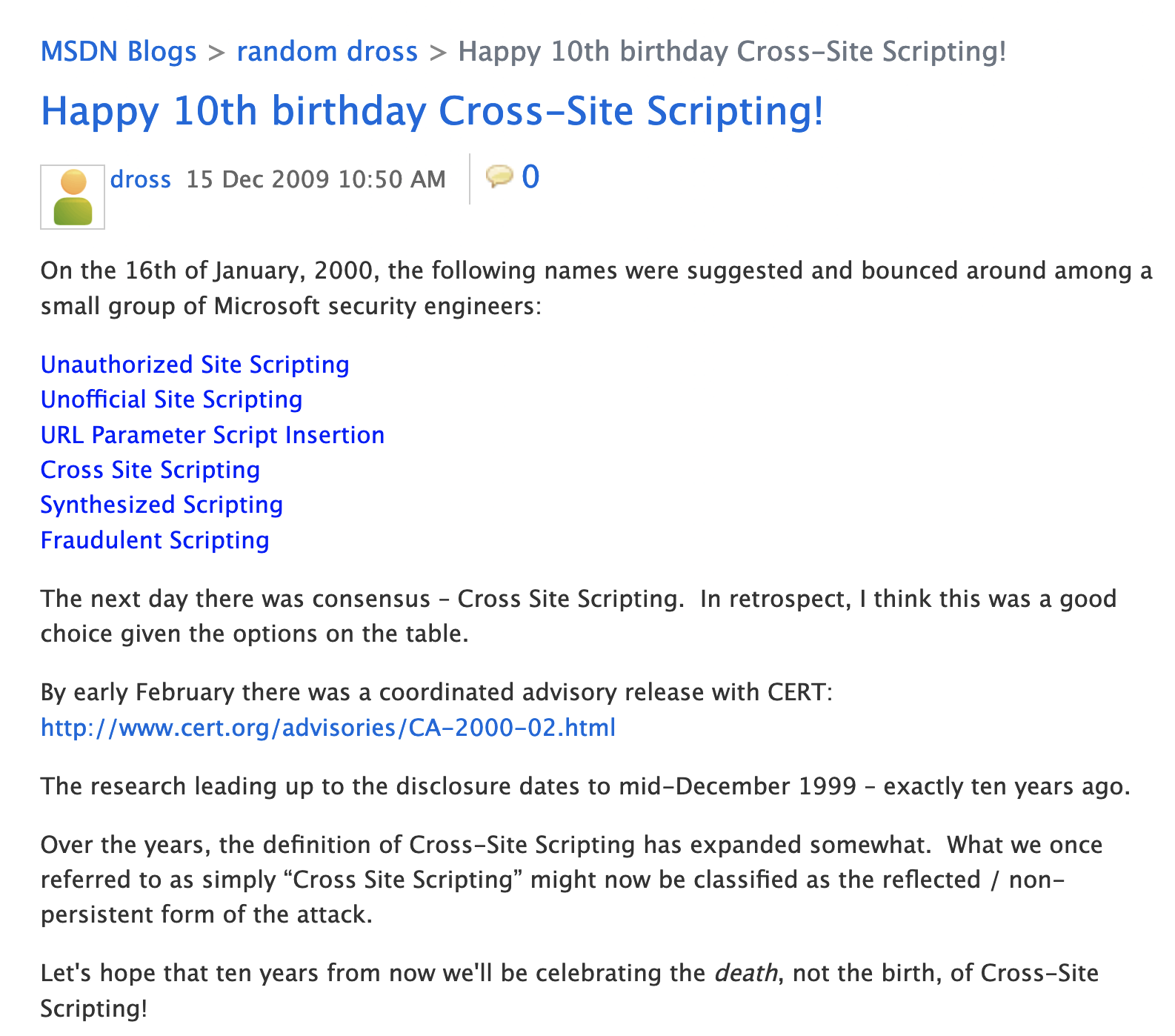

From the title of the article published on Microsoft’s MSDN blog in December 2009: Happy 10th birthday Cross-Site Scripting!, we can see that the term XSS (Cross-Site Scripting) was born around December 1999, which is more than 20 years ago now.

(The screenshot below is from the above link)

The original article ends with this paragraph:

Let’s hope that ten years from now we’ll be celebrating the death, not the birth, of Cross-Site Scripting!

Unfortunately, ten years after 2009, which is 2019, XSS is still active. In 2017, it ranked seventh in the OWASP top 10, and in the 2021 version, it was merged into the third-ranked Injection category.

The article also mentions CERT® Advisory CA-2000-02 Malicious HTML Tags Embedded in Client Web Requests, which allows us to take a glimpse of the earliest appearance of XSS. Let’s take a brief look at the content of this webpage:

A web site may inadvertently include malicious HTML tags or script in a dynamically generated page based on unvalidated input from untrustworthy sources. This can be a problem when a web server does not adequately ensure that generated pages are properly encoded to prevent unintended execution of scripts, and when input is not validated to prevent malicious HTML from being presented to the user.

In the Overview section, the core concept of XSS is actually explained very clearly: the server does not verify the input or encoding, allowing attackers to insert some malicious HTML tags or scripts.

Malicious code provided by one client for another client

Sites that host discussion groups with web interfaces have long guarded against a vulnerability where one client embeds malicious HTML tags in a message intended for another client. For example, an attacker might post a message like

Hello message board. This is a message.<SCRIPT>malicious code</SCRIPT>This is the end of my message.When a victim with scripts enabled in their browser reads this message, the malicious code may be executed unexpectedly. Scripting tags that can be embedded in this way include

<SCRIPT><OBJECT>,<APPLET>, and<EMBED>.When client-to-client communications are mediated by a server, site developers explicitly recognize that data input is untrustworthy when it is presented to other users. Most discussion group servers either will not accept such input or will encode/filter it before sending anything to other readers.

This paragraph is later referred to as “Stored XSS (also known as Persistent XSS)”. Suppose there is a discussion forum where people can leave messages, and a malicious attacker can leave such content:

Hello message board. This is a message.

<SCRIPT>malicious code</SCRIPT>

This is the end of my message.When other users see this message, because there is <script> in the message, they will execute the JavaScript code left by the attacker.

In addition to this, <object>, <applet>, and <embed> can also be used to execute JavaScript (by the way, the applet tag should be useless, see: Don’t break the Web: SmooshGate and keygen).

Malicious code sent inadvertently by a client for itself

Many Internet web sites overlook the possibility that a client may send malicious data intended to be used only by itself. This is an easy mistake to make. After all, why would a user enter malicious code that only the user will see?

However, this situation may occur when the client relies on an untrustworthy source of information when submitting a request. For example, an attacker may construct a malicious link such as

<A HREF="http://example.com/comment.cgi? mycomment=<SCRIPT>malicious code</SCRIPT>"> Click here</A>When an unsuspecting user clicks on this link, the URL sent to example.co includes the malicious code. If the web server sends a page back to the user including the value of mycomment, the malicious code may be executed unexpectedly on the client. This example also applies to untrusted links followed in email or newsgroup messages.

This paragraph is very interesting. The title is “Malicious code sent inadvertently by a client for itself”, and the content sent is basically only visible to oneself.

For example, the parameter “mycomment” in the URL will be reflected on the screen, so if it is like http://example.com/comment.cgi?mycomment=123, 123 will appear on the screen.

But what can you do if only you can see it?

Because information is passed through the query string in the URL, such a link can be generated: http://example.com/comment.cgi?mycomment=<SCRIPT>malicious code</SCRIPT>, and then this link is passed to others. When others click on it, <SCRIPT>malicious code</SCRIPT> will appear on the screen, achieving XSS in the same way.

This is another classification of XSS: Reflected XSS, and your input will be reflected on the screen.

The difference between these two types is that Stored XSS, as its name suggests, the XSS payload is saved. In the case of a discussion forum, the article is saved in the database, while Reflected XSS is not.

Taking PHP as an example, the code for Reflected XSS may look like this:

<?php

$comment = $_GET['comment'];

?>

<div>

<?= $comment ?>

</div>The GET parameter is directly reflected on the screen, so each time the payload must be passed in through the “comment” parameter, otherwise XSS will not be triggered.

Taking the “discussion forum” website mentioned above as an example, the destructive power of Stored XSS should be stronger, because as long as you click on your article, you will be attacked. You can think of it as posting an article on PTT. As long as a netizen clicks into the article, they will be attacked, which is quite easy to trigger.

But Reflected XSS is different. It requires the user to click on a link to trigger the attack, such as leaving a link in a PTT post and the user actively clicking on that link to trigger the XSS.

Other parts of the article are also interesting, such as the fact that even if JavaScript is disabled, the screen can still be tampered with using HTML and CSS. There are also ways to fix it, which can be found here: Understanding Malicious Content Mitigation for Web Developers

In addition to the familiar content encoding, there is another way to “specify the encoding method”. This encoding refers to UTF-8, ISO-8859-1, and big5 encoding. Although most websites nowadays use UTF-8, it was not always the case in the past. In the past, browsers also supported encoding methods such as UTF-7, which could achieve XSS even without using special characters:

<html>

<head><title>test page</title></head>

<body>

+ADw-script+AD4-alert(1)+ADw-/script+AD4-

</body>

</html>Example taken from: XSS and Character Set, which mentions more similar issues, but most of them occurred on earlier browsers.

The Birth of the Third Type of XSS Classification

Anyone who has read about XSS knows that there are probably three most well-known types of XSS classification:

- Stored XSS (Persistent XSS)

- Reflected XSS (Non-Persistent XSS)

- DOM-based XSS

Before we continue, let me ask you two questions.

The first question is, suppose I post an article with the content <img src=x onerror=alert(1)>, and the page code that displays the article is like this:

<script>

getPost({ id: 1}).then(post => {

document.querySelector('.article').innerHTML = post.content

})

</script>Due to the use of innerHTML, there is an XSS vulnerability in this situation. My comment is indeed “saved” in the database, but at the same time, the content is changed using DOM. Should this XSS be classified as Stored XSS or DOM-based XSS?

The second question is, suppose there is a piece of code in the webpage that looks like this:

<script>

document.querySelector(".search").innerHTML = decodeURIComponent(location.search)

</script>This can obviously create an XSS vulnerability through the query string. This XSS does reflect the user’s input and is not stored in the database, but it changes the content using DOM. Should it be classified as Reflected XSS or DOM-based XSS?

Before reading on, think about these two questions.

Let’s talk about my previous answer first. I used the following definition to classify these:

- If my XSS payload (such as

<script>alert(1)</script>) exists in the database, it is Stored XSS. - If not, then it depends on whether my payload is output directly from the backend or assigned through DOM. The former is Reflected, and the latter is DOM-based.

Later, I realized that this classification method was wrong because I was misled by the term “stored” and did not realize the historical background behind it.

What does this mean? When XSS first appeared in 1999, Ajax did not exist (it was born in 2005), so data exchange between the front and back ends should be sent to the server through forms and rendered directly.

In other words, in 1999, there were basically no operations that used JavaScript to change the content of the screen, even if there were, they were some relatively insignificant operations. But in 2021, it is different. In this era of SPA, data is basically called through JavaScript to call the API, and then the screen is changed after the data is obtained. The backend only provides data, and the frontend relies on JavaScript to render. This is completely different from 20 years ago.

Of the three types of XSS classification, the first two, Stored and Reflected, existed when XSS was born, and the third type appeared five years later (the term or classification to define it, not the attack), and the source should be this article: DOM Based Cross Site Scripting or XSS of the Third Kind.

The following paragraph is from the “Introduction” section of the article:

XSS is typically categorized into “non-persistent” and “persistent” (“reflected” and “stored” accordingly, as defined in [4]). “Non-persistent” means that the malicious (Javascript) payload is echoed by the server in an immediate response to an HTTP request from the victim. “Persistent” means that the payload is stored by the system, and may later be embedded by the vulnerable system in an HTML page provided to a victim.

The key point is that both the “Stored” and “Reflected” categories require the payload to be directly rendered by the backend. The third category mentioned in this article, DOM-based, refers to payloads rendered by the frontend. This is the biggest difference between the third category and the first two.

When determining XSS, the first thing to confirm is whether the payload is rendered by the frontend or backend. If it is rendered by the frontend, regardless of where the data comes from (database, URL, or anywhere else), it is DOM-based XSS. If it is rendered by the backend, then it is either Stored or Reflected.

Therefore, both of the previous questions are classified as DOM-based XSS because they are rendered by the frontend.

The article provides a similar example:

<HTML>

<TITLE>Welcome!</TITLE>

Hi

<SCRIPT>

var pos=document.URL.indexOf("name=")+5;

document.write(document.URL.substring(pos,document.URL.length));

</SCRIPT>

<BR>

Welcome to our system

…

</HTML>The comment in the article specifically states:

The malicious payload was not embedded in the raw HTML page at any time (unlike the other flavors of XSS).

Because the payload does not actually exist in any HTML page (it is changed later using JavaScript), it does not belong to Stored or Reflected, but is a new type of XSS.

As for the repair method, since it is rendered by JavaScript on the frontend, encoding is the responsibility of the frontend developer. A common method is as follows (code taken from Sanitizing user input before adding it to the DOM in Javascript):

function sanitize(string) {

const map = {

'&': '&',

'<': '<',

'>': '>',

'"': '"',

"'": ''',

"/": '/',

};

const reg = /[&<>"'/]/ig;

return string.replace(reg, (match)=>(map[match]));

}However, it is important to note that this is not enough to prevent XSS. The defense against XSS is more complicated because it requires handling different situations. For example, if your output needs to be placed inside <a href="">, you need to consider payloads in the form of javascript:alert(1). In this case, the sanitize function above is not useful.

Conclusion

The reason for the initial confusion was because the vulnerability classification reported on the HITCON ZeroDay platform was changed, which made me realize that I had misunderstood the classification. I would like to thank the reviewers for their work.

In addition to these classifications, there are other ways to classify XSS, such as Self XSS, where users need to enter their own XSS payloads, or Mutation XSS, which exploits inconsistent HTML parsing. These are all interesting applications of XSS, and I will share more with you in the future.

Comments