Introduction

A supply chain attack targets vulnerabilities upstream to launch an attack, as contaminating upstream will also contaminate downstream.

Taking front-end as an example, do you realize the risks associated with using npm packages or third-party scripts imported into your code, which are called “upstream”?

This article will use cdnjs as an example to show front-end supply chain attacks and defenses.

cdnjs

When writing front-end code, you often encounter many situations where you need to use third-party libraries, such as jQuery or Bootstrap (the former is downloaded 4 million times a week on npm, and the latter is downloaded 3 million times). Leaving aside the fact that most people now use webpack to package their code, in the past, for such requirements, you either downloaded a file yourself or used a ready-made CDN to load it.

cdnjs is one of the sources, and its official website looks like this:

In addition to cdnjs, there are other websites that provide similar services. For example, on the jQuery official website, you can see their own code.jquery.com, and Bootstrap uses another service called jsDelivr.

Let’s take a practical example!

Suppose I am currently working on a website that requires jQuery. I need to use the <script> tag to load the jQuery library into the page, and the source can be:

- My own website

- jsDelivr: https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/[email protected]/dist/jquery.min.js

- cdnjs: https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/jquery/3.6.0/jquery.min.js

- jQuery official website: https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.6.0.min.js

Suppose I finally choose the URL provided by the jQuery official website, and then I will write this HTML:

<script src="https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.6.0.min.js"></script>In this way, the jQuery library is loaded, and other code can use the functions it provides.

So why should I choose a CDN instead of downloading it and putting it on my own website? There may be several reasons:

- Laziness, using someone else’s is the fastest

- Budget considerations, using someone else’s website can save your own website’s traffic costs and load

- Speed considerations

The third point of speed consideration is worth explaining in particular. If the loaded library comes from a CDN, the download speed may be faster.

The first reason for being faster is that they are originally doing CDN, so there may be nodes in different countries. Suppose your host is in the United States. If you use your own website, Taiwanese users have to connect to the US server to fetch these libraries. However, if you use the URL provided by the CDN, you may only need to connect to the Taiwanese node, saving some latency.

The second reason is that if everyone is using this CDN, the probability of it being cached will increase. For example, suppose Facebook also uses cdnjs to load jQuery 3.6.0. If my website also uses the same service to load the same library, for browsers that have visited Facebook, they do not need to download the file again because it has already been downloaded and cached.

(2021-08-09 Supplement: Thanks to Ho Hong Yip for correcting me in the front-end community on Facebook after the article was published. The current browser has added a limit to the cache, that is, the cache across websites (more specifically, based on eTLD+1) will be separated. Therefore, even if Facebook has loaded jQuery 3.6.0, when users visit your website, they still need to download it again. For more detailed introduction, you can see this article: Gaining security and privacy by partitioning the cache. In this way, it seems that there is one less reason to use public CDNs? But Web Shared Libraries mentioned at the end of the article wants to solve this problem, but it seems to be in the early stage.)

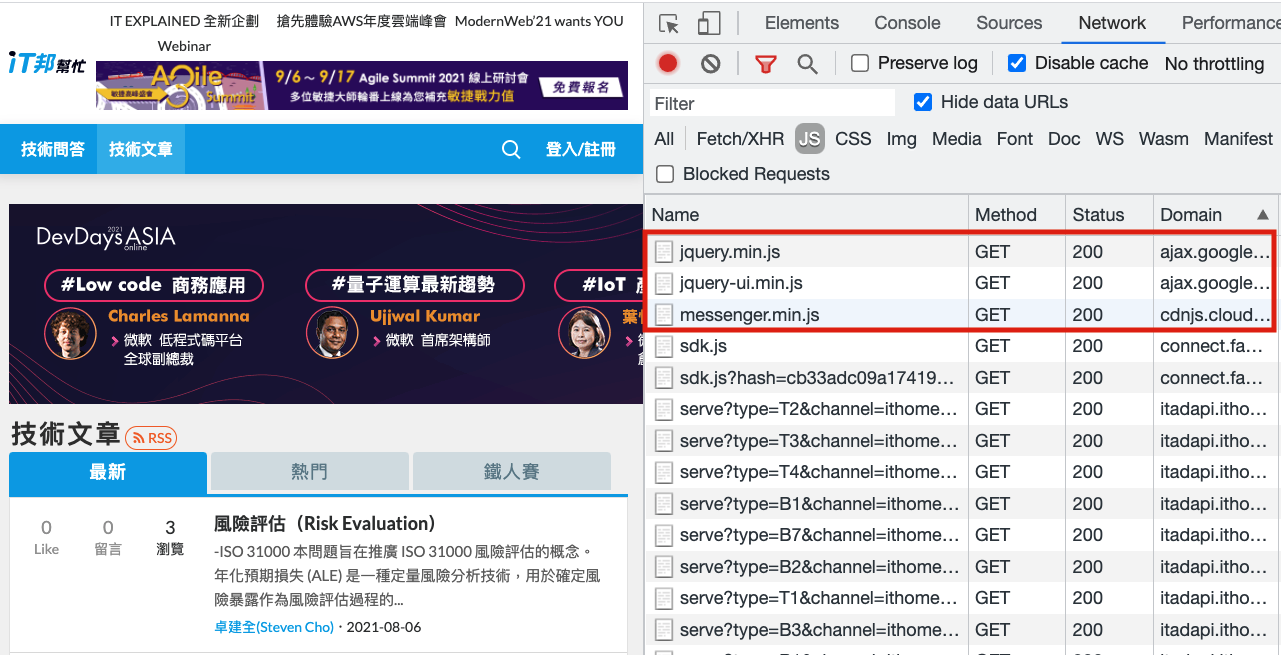

Taking the familiar iT 邦幫忙 website as an example, it uses resources from Google and cdnjs:

We talked about the advantages of using third-party CDNs earlier, but what are the disadvantages?

The first disadvantage is that if the CDN goes down, your website may go down with it, or at least experience slow connections. For example, if my website loads jQuery from cdnjs, but cdnjs suddenly becomes slow, my website will also become slow, and be affected as well.

And the company behind cdnjs, Cloudflare, has indeed had some issues, affecting many websites.

The second disadvantage is that if the CDN is hacked and the library you imported is injected with malicious code, your website will also be compromised. This type of attack is the topic of this article: “supply chain attack,” which infiltrates from upstream and affects downstream.

Some people may think, “These big companies are unlikely to be hacked, right? And with so many people using this service, someone must be monitoring it.”

Next, let’s look at a real case.

Analyzing the cdnjs RCE vulnerability

On July 16, 2021, a security researcher @ryotkak published an article on his blog titled Remote code execution in cdnjs of Cloudflare (hereinafter referred to as “the author”).

Remote code execution, or RCE for short, is a high-risk vulnerability that allows attackers to execute arbitrary code. The author discovered an RCE vulnerability in cdnjs, which, if exploited, could control the entire cdnjs service.

The author’s blog post describes the process in great detail. Here, I will briefly explain how the vulnerability was formed, which involves two vulnerabilities.

First, Cloudflare has open-sourced cdnjs-related code on GitHub, and one of its automatic update features caught the author’s attention. This feature automatically retrieves packaged files from npm, which are compressed files in .tgz format, and after decompressing them, processes the files and copies them to the appropriate location.

The author knew that there might be vulnerabilities in using archive/tar to decompress files in Go, because the decompressed files are not processed, so the file names can look like this: ../../../../../tmp/temp.

What’s the problem with this?

Suppose you have a piece of code that copies files and does something like this:

- Concatenate the destination and file name to create the target location and create a new file.

- Read the original file and write it to the new file.

If the destination is /packages/test and the file name is abc.js, a new file will be created at /packages/test/abc.js.

If the destination is the same, but the file name is ../../../tmp/abc.js, a file will be written to /package/test/../../../tmp/abc.js, which is /tmp/abc.js.

Therefore, using this technique, files can be written to any location with permissions! And cdnjs’s code has a similar vulnerability that can write files to any location. If this vulnerability can be exploited to overwrite the files that are scheduled to be automatically executed, RCE can be achieved.

When the author was about to create a POC to verify this, he suddenly became curious about how the Git auto-update feature worked (the above discussion about compressed files was for npm).

After researching it, the author found a piece of code for copying files related to Git repo auto-updates, which looks like this:

func MoveFile(sourcePath, destPath string) error {

inputFile, err := os.Open(sourcePath)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("Couldn't open source file: %s", err)

}

outputFile, err := os.Create(destPath)

if err != nil {

inputFile.Close()

return fmt.Errorf("Couldn't open dest file: %s", err)

}

defer outputFile.Close()

_, err = io.Copy(outputFile, inputFile)

inputFile.Close()

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("Writing to output file failed: %s", err)

}

// The copy was successful, so now delete the original file

err = os.Remove(sourcePath)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("Failed removing original file: %s", err)

}

return nil

}It doesn’t look like much, just copying files, opening a new file, and copying the contents of the old file into it.

But if the original file is a symbolic link, it’s different. Before we continue, let’s briefly explain what a symbolic link is.

The concept of a symbolic link is similar to the “shortcut” we used to see on Windows. This shortcut is just a link that points to the real target.

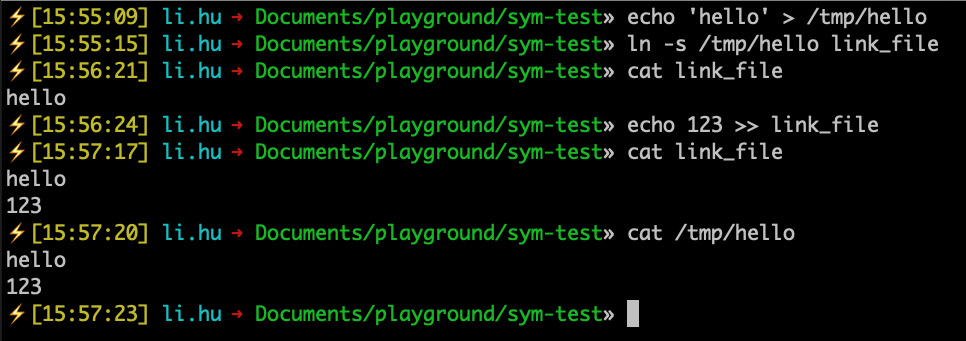

In Unix-like systems, you can use ln -s target_file link_name to create a symbolic link. Here’s an example that will make it easier to understand.

First, I create a file with the content “hello” at /tmp/hello. Then I create a symbolic link in the current directory that points to the hello file I just created: ln -s /tmp/hello link_file.

Next, if I print the contents of link_file, it will show hello, because it is actually printing the contents of /tmp/hello. If I write data to link_file, it is actually writing to /tmp/hello.

Next, let’s try writing a piece of Node.js code to copy a file and see what happens:

node -e 'require("fs").copyFileSync("link_file", "test.txt")'After execution, we found that there is a new file test.txt in the directory, and its contents are the contents of the file /tmp/hello.

Therefore, when a program executes a file copy, it is not “copying a symbolic link”, but “copying the content of the file it points to”.

Therefore, the file copying code mentioned earlier in Go, if there is a file that points to a symbolic link /etc/passwd, after copying, a file with the content /etc/passwd will be generated.

We can add a symbolic link named test.js in the Git file, which points to /etc/passwd. After being copied by cdnjs, a test.js file will be generated, and its contents will be the contents of /etc/passwd!

In this way, an arbitrary file read vulnerability is obtained.

To summarize, the author found two vulnerabilities, one can write files and the other can read files. If you accidentally overwrite important files when writing files, the system will crash. Therefore, the author decided to start with reading files to do POC, created a Git repository and released a new version, waited for cdnjs to automatically update, and finally triggered the file reading vulnerability. The content read from the file can be seen in the JS published by cdnjs.

The file the author read is /proc/self/environ (he originally wanted to read another file /proc/self/maps), which contains environment variables, and a GitHub API key is also in it. This key has write permissions to the repo under cdnjs, so using this key, you can directly modify the code of cdnjs or the cdnjs website, thereby controlling the entire service.

The above is an explanation of the cdnjs vulnerability. If you want to see more technical details or detailed developments, you can read the original author’s blog post, which records many details. In short, even services maintained by large companies have the risk of being invaded.

As a front-end engineer, how should we defend?

So how can we defend against this type of vulnerability? Or maybe we can’t defend against it at all?

The browser actually provides a function: “Do not load if the file has been tampered with”, so even if cdnjs is invaded and the jQuery file is tampered with, my website will not load the new jQuery file, avoiding file pollution attacks.

On cdnjs, when you decide to use a certain library, you can choose to copy the URL or copy the script tag. If you choose the latter, you will get this content:

<script

src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/react/17.0.2/umd/react.production.min.js"

integrity="sha512-TS4lzp3EVDrSXPofTEu9VDWDQb7veCZ5MOm42pzfoNEVqccXWvENKZfdm5lH2c/NcivgsTDw9jVbK+xeYfzezw=="

crossorigin="anonymous"

referrerpolicy="no-referrer">

</script>crossorigin="anonymous" I mentioned in my previous article: DoS attack using Cookie features: Cookie bomb, using the CORS method to send requests can avoid bringing cookies to the backend.

The other tag above, integrity, is the key to defense. This attribute will let the browser verify whether the resource to be loaded meets the hash value provided. If it does not match, it means that the file has been tampered with and the resource will not be loaded. Therefore, even if cdnjs is invaded and the hacker replaces the react.js I originally used, the browser will not load the contaminated code because the hash value does not match.

If you want to know more, you can refer to MDN, where there is a page Subresource Integrity specifically for this.

However, this method can only prevent “already introduced scripts” from being tampered with. If you happen to copy the script after the hacker has tampered with the file, it will be useless because the file has already been tampered with.

Therefore, if you want to completely avoid this risk, do not use these third-party services, put these libraries on your own CDN, so the risk changes from third-party risk to your own service risk. Unless your own service is taken down, these libraries should not have any problems.

However, it should be noted that you still cannot avoid other supply chain attack risks. Because even if you don’t use a third-party library CDN, you still need to download these libraries from somewhere else, right? For example, npm, your library source may be here, which means that if npm is invaded and the files on it are tampered with, it will still affect your service. This is a supply chain attack, which does not directly attack you, but penetrates from other upstreams.

However, this type of risk can be detected during build time through some static scanning services to see if tampered files or malicious code can be detected. Some companies also set up an internal npm registry that does not synchronize directly with external npm to ensure that the libraries used will not be tampered with.

Additional risk: CSP bypass

In addition to the supply chain security risks mentioned above, there is actually another potential risk when using third-party JS, which is the bypass of CSP (Content Security Policy). Now many websites will set up CSP to block untrusted sources, such as only allowing JS files from a certain domain, or not allowing inline events and eval, etc.

If your website uses cdnjs scripts, your CSP will inevitably have the https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com URL. Compared to the complete path, more people tend to allow everything from the entire domain, because you may use multiple libraries and are too lazy to add them one by one.

At this time, if the website has an XSS vulnerability, the CSP should have a defensive effect in general, preventing the execution of these untrusted codes. Unfortunately, the https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com path in CSP allows attackers to easily bypass CSP.

First, let’s talk about the principle. The principle is that cdnjs has millions of different libraries besides the library you want to use, and some of the functions provided by these libraries allow attackers to execute arbitrary code without executing JS.

For example, AngularJS has a vulnerability in old versions called Client-Side Template Injection, which only requires HTML to execute code. Techniques like “using other legitimate scripts to help you execute attack code” are called script gadgets. To learn more, you can refer to: security-research-pocs/script-gadgets

Assuming that our CSP only allows https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com, how to bypass it? I found these two great resources:

- Bypassing path restriction on whitelisted CDNs to circumvent CSP protections - SECT CTF Web 400 writeup

- H5SC Minichallenge 3: “Sh*t, it’s CSP!”

Just use AngularJS + Prototype these two libraries, you can perform XSS under the condition of meeting CSP (only introducing scripts under cdnjs). I made a simple demo: https://aszx87410.github.io/demo/csp_bypass/cdnjs.html

The complete code is as follows:

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>CSP bypass</title>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'none'; script-src https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com">

</head>

<body>

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/prototype/1.7.2/prototype.js"></script>

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/angular.js/1.0.1/angular.js"></script>

<div ng-app ng-csp>

{{$on.curry.call().alert('xss')}}

</div>

</body>

</html>To avoid this type of CSP bypass, you can only hardcode the cdnjs path in CSP and write the entire script URL instead of just writing the domain. Otherwise, this type of CSP will actually help attackers break through the limitations of CSP and perform XSS attacks.

Conclusion

There are countless attack methods, and researchers who discovered the vulnerability in cdnjs have recently been fond of supply chain attacks. Not only cdnjs, but also Homebrew, PyPI, and even @types have been found to have vulnerabilities.

If you want to directly import third-party URLs on a page using script, be sure to first confirm that the other party’s website is trustworthy. If possible, also add the integrity attribute to avoid file tampering and affecting your own service. Also pay attention to the CSP settings. For websites like cdnjs, if only the domain is set, there are already feasible bypass methods, so please be careful when setting it up.

When it comes to front-end security, everyone first thinks of XSS, then CSRF, and then maybe nothing else. This article hopes to introduce front-end engineers to supply chain attacks through the vulnerability in cdnjs. As long as you are aware of this attack method, you will pay more attention to it in future development and notice the risks associated with importing third-party libraries.

Comments