Preface

If you don’t know what XSS (Cross-site Scripting) is, in simple terms, it is when a hacker can execute JavaScript code on your website. Since it can be executed, it is possible to steal the user’s token, impersonate the user’s identity to log in, even if the token cannot be stolen, it can still modify the page content, or redirect the user to a phishing website, and so on.

To prevent XSS, it is necessary to prevent hackers from executing code on the website, and there are many ways to defend against it. For example, CSP (Content-Security-Policy) can be used as an HTTP response header to prevent the execution of inline scripts or restrict the domains from which scripts can be loaded. Trusted Types can also be used to prevent some potential attacks and specify rules, or use some libraries that filter XSS, such as DOMPurify and js-xss.

But is it enough to use these? Yes and no.

If used correctly, of course, there is no problem, but if there are incorrect settings, there may still be XSS vulnerabilities.

Recently, I just transferred from a company to a cybersecurity team, Cymetrics, and when I was researching some websites, I found a ready-made case. Therefore, this article uses this ready-made case to illustrate what is called incorrect settings and what impact this setting will have.

Incorrect settings, unexpected results

Matters News is a decentralized writing community platform, and all the code is open source!

For this kind of blog platform, what I like to see most is how they handle content filtering. With a curious and research-oriented attitude, let’s take a look at how they do it in the article and comment sections.

The server-side filtering code is here: matters-server/src/common/utils/xss.ts:

import xss from 'xss'

const CUSTOM_WHITE_LISTS = {

a: [...(xss.whiteList.a || []), 'class'],

figure: [],

figcaption: [],

source: ['src', 'type'],

iframe: ['src', 'frameborder', 'allowfullscreen', 'sandbox'],

}

const onIgnoreTagAttr = (tag: string, name: string, value: string) => {

/**

* Allow attributes of whitelist tags start with "data-" or "class"

*

* @see https://github.com/leizongmin/js-xss#allow-attributes-of-whitelist-tags-start-with-data-

*/

if (name.substr(0, 5) === 'data-' || name.substr(0, 5) === 'class') {

// escape its value using built-in escapeAttrValue function

return name + '="' + xss.escapeAttrValue(value) + '"'

}

}

const ignoreTagProcessor = (

tag: string,

html: string,

options: { [key: string]: any }

) => {

if (tag === 'input' || tag === 'textarea') {

return ''

}

}

const xssOptions = {

whiteList: { ...xss.whiteList, ...CUSTOM_WHITE_LISTS },

onIgnoreTagAttr,

onIgnoreTag: ignoreTagProcessor,

}

const customXSS = new xss.FilterXSS(xssOptions)

export const sanitize = (string: string) => customXSS.process(string)What is worth noting here is this part:

const CUSTOM_WHITE_LISTS = {

a: [...(xss.whiteList.a || []), 'class'],

figure: [],

figcaption: [],

source: ['src', 'type'],

iframe: ['src', 'frameborder', 'allowfullscreen', 'sandbox'],

}This part allows the tags and attributes that can be used, and the content of the attributes will also be filtered. For example, although iframe and src attributes are allowed, <iframe src="javascript:alert(1)"> will not work because src starting with javascript: will be filtered out.

It’s not enough to just look at the server-side, we also need to see how the client-side renders.

For displaying articles, it is like this: src/views/ArticleDetail/Content/index.tsx

<>

<div

className={classNames({ 'u-content': true, translating })}

dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{

__html: optimizeEmbed(translation || article.content),

}}

onClick={captureClicks}

ref={contentContainer}

/>

<style jsx>{styles}</style>

</>Matters’ frontend uses React, and everything rendered in React is escaped by default, so there are basically no XSS vulnerabilities. But sometimes we don’t want it to be filtered, such as the content of an article, we may need some tags to be rendered as HTML, and then we can use dangerouslySetInnerHTML, which will render the content directly as innerHTML and will not be filtered.

So generally, the approach is to use js-xss + dangerouslySetInnerHTML to ensure that the rendered content is HTML but not XSS.

Here, before passing in dangerouslySetInnerHTML, there is a function called optimizeEmbed, and you can continue to trace down to src/common/utils/text.ts:

export const optimizeEmbed = (content: string) => {

return content

.replace(/\<iframe /g, '<iframe loading="lazy"')

.replace(

/<img\s[^>]*?src\s*=\s*['\"]([^'\"]*?)['\"][^>]*?>/g,

(match, src, offset) => {

return /* html */ `

<picture>

<source

type="image/webp"

media="(min-width: 768px)"

srcSet=${toSizedImageURL({ url: src, size: '1080w', ext: 'webp' })}

onerror="this.srcset='${src}'"

/>

<source

media="(min-width: 768px)"

srcSet=${toSizedImageURL({ url: src, size: '1080w' })}

onerror="this.srcset='${src}'"

/>

<source

type="image/webp"

srcSet=${toSizedImageURL({ url: src, size: '540w', ext: 'webp' })}

/>

<img

src=${src}

srcSet=${toSizedImageURL({ url: src, size: '540w' })}

loading="lazy"

/>

</picture>

`

}

)

}Here, RegExp is used to extract the img src, and then the HTML is directly spliced together using string concatenation. Then, see toSizedImageURL:

export const toSizedImageURL = ({ url, size, ext }: ToSizedImageURLProps) => {

const assetDomain = process.env.NEXT_PUBLIC_ASSET_DOMAIN

? `https://${process.env.NEXT_PUBLIC_ASSET_DOMAIN}`

: ''

const isOutsideLink = url.indexOf(assetDomain) < 0

const isGIF = /gif/i.test(url)

if (!assetDomain || isOutsideLink || isGIF) {

return url

}

const key = url.replace(assetDomain, ``)

const extedUrl = changeExt({ key, ext })

const prefix = size ? '/' + PROCESSED_PREFIX + '/' + size : ''

return assetDomain + prefix + extedUrl

}As long as the domain is the assets’ domain and meets other conditions, it will be returned after some string processing.

Seeing this, you can roughly understand the entire rendering process of the article.

js-xss is used to filter on the server-side, and dangerouslySetInnerHTML is used to render on the client-side. Among them, some processing is done on the img tag, and the img is changed to load different images for different resolutions or screen sizes using picture + source.

The above is the entire process of rendering articles on this website. Before continuing to read, you can think about whether there are any problems?

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

== Lightning Protection Separator ==

First problem: Incorrect attribute filtering

Did you notice any problems with the filtering here?

const CUSTOM_WHITE_LISTS = {

a: [...(xss.whiteList.a || []), 'class'],

figure: [],

figcaption: [],

source: ['src', 'type'],

iframe: ['src', 'frameborder', 'allowfullscreen', 'sandbox'],

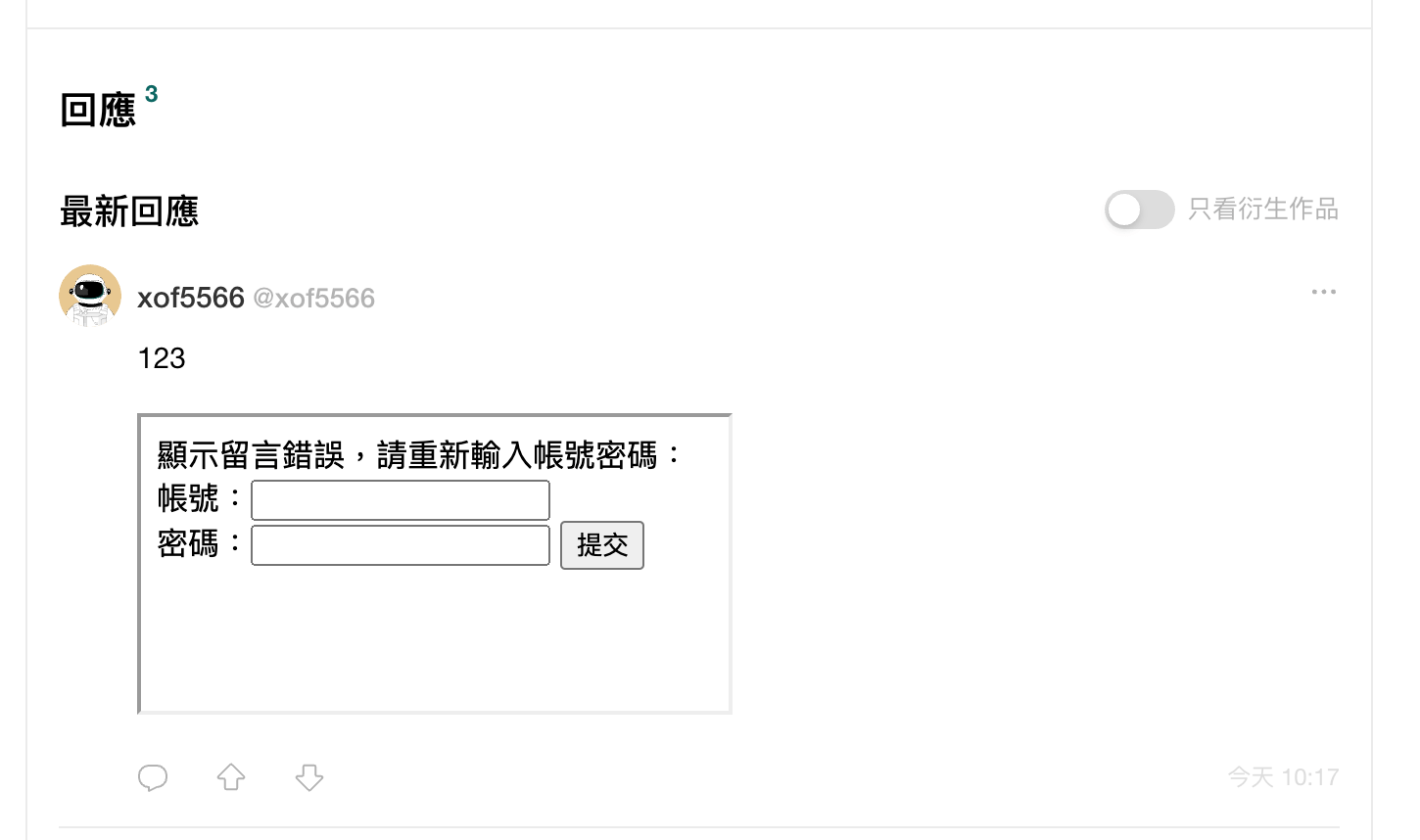

}Opening iframe should be to allow users to embed things like YouTube videos, but the problem is that this website does not specify a valid domain using CSP, so the src here can be filled in randomly. I can make a website myself and embed it using iframe. If the webpage is designed well, it will look like a part of this website:

The above is just a random example, mainly to give you an idea. If you really want to attack, you can make it more sophisticated and more attractive.

If that’s all, whether the attack can succeed depends on whether the content can be trusted by the user. But actually, more can be done. Do you know that you can manipulate the external website inside the iframe?

The things that cross-origin windows can access are limited, and the only thing that can be changed is location, which means that we can redirect the embedded website:

<script>

top.location = 'https://google.com'

</script>If I do this, I can redirect the entire website to anywhere. The simplest application that can be thought of is to redirect to a phishing website. The success rate of such phishing websites is relatively high because users may not even realize that they have been redirected to another website.

In fact, browsers have defenses against such redirects, and the above code will produce an error:

Unsafe attempt to initiate navigation for frame with origin ‘https://matters.news‘ from frame with URL ‘https://53469602917d.ngrok.io/‘. The frame attempting navigation is targeting its top-level window, but is neither same-origin with its target nor has it received a user gesture. See https://www.chromestatus.com/features/5851021045661696.

Uncaught DOMException: Failed to set the ‘href’ property on ‘Location’: The current window does not have permission to navigate the target frame to ‘https://google.com‘

Because it is not the same origin, the iframe will be prevented from redirecting the top-level window.

However, this can be bypassed, and it will use the sandbox attribute. This attribute actually specifies what permissions the embedded iframe has, so as long as it is changed to: <iframe sandbox="allow-top-navigation allow-scripts allow-same-origin" src=example.com></iframe>, it can successfully redirect the top-level window and redirect the entire website.

This vulnerability has been found in both GitLab and codimd.

There are several ways to fix this issue. The first one is to remove the sandbox attribute so that it cannot be used. If it is needed somewhere, the value inside should be checked, and the more dangerous allow-top-navigation should be removed.

Another way is to restrict the location of the iframe src, which can be done at different levels. For example, filtering src in the code and only allowing specific domains, or using CSP:frame-src to let the browser block domains that do not comply.

The second issue: Unfiltered HTML

The first issue can cause the biggest danger, probably just a redirect (the codimd article says that XSS can be done in Safari, but I can’t do it QQ). However, there is a bigger problem besides this, which is here:

<>

<div

className={classNames({ 'u-content': true, translating })}

dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{

__html: optimizeEmbed(translation || article.content),

}}

onClick={captureClicks}

ref={contentContainer}

/>

<style jsx>{styles}</style>

</>article.content is an HTML string filtered by js-xss, so it is safe. However, here it goes through an optimizeEmbed to do custom conversion, which is a more dangerous thing to do after filtering, because if there is negligence in the process, it will cause an XSS vulnerability.

In the conversion, there is a piece of code:

<source

type="image/webp"

media="(min-width: 768px)"

srcSet=${toSizedImageURL({ url: src, size: '1080w', ext: 'webp' })}

onerror="this.srcset='${src}'"

/>Looking closely at this code, if ${toSizedImageURL({ url: src, size: '1080w', ext: 'webp' })} or src can be controlled, there is a chance to change the content of the attribute or add a new attribute.

I originally wanted to insert a malicious src to make onerror become onerror="this.srcset='test';alert(1)" and other code, but I later found that the onerror event of the source under the picture seems to be invalid, even if there is an error in srcset, it will not trigger, so it is useless.

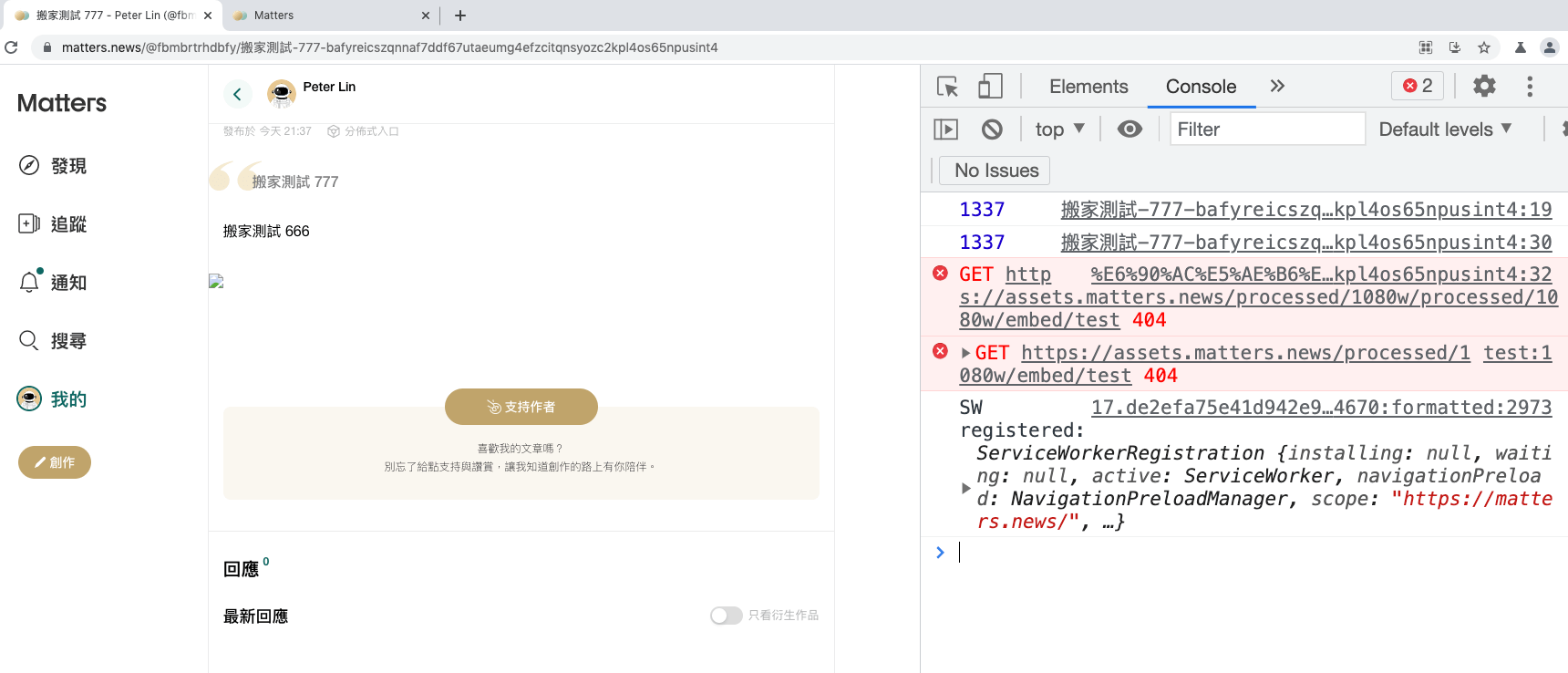

Therefore, I focused on srcSet and inserting new attributes. Here, onanimationstart can be used, which is an event that will be triggered when the animation starts, and the name of the animation can be found in CSS. Fortunately, I found a keyframe called spinning.

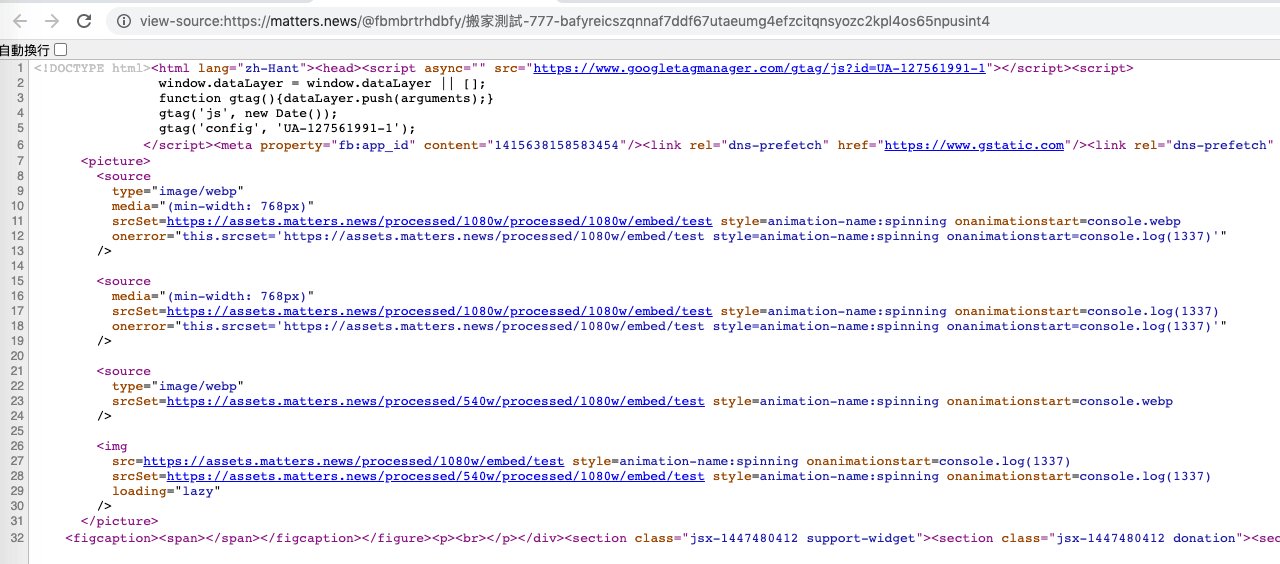

So if the img src is: https://assets.matters.news/processed/1080w/embed/test style=animation-name:spinning onanimationstart=console.log(1337)

The combined code is:

<source

type="image/webp"

media="(min-width: 768px)"

srcSet=https://assets.matters.news/processed/1080w/embed/test

style=animation-name:spinning

onanimationstart=console.log(1337)

onerror="this.srcset='${src}'"

/>In this way, an XSS vulnerability is created:

There are several ways to fix it:

- Add a CSP header to prevent the execution of inline scripts (this is more difficult to achieve because it may conflict with existing things and requires more time to process).

- Filter the img url passed in (there is still a risk if the filtering is not done well).

- Change the HTML first and then call js-xss to filter out the attributes that should not exist.

Summary

We found two vulnerabilities:

- Redirect users to any location through

<iframe> - Execute an XSS attack on the article page through

<source>

What kind of attack can actually be done?

First, use the second vulnerability to publish an article with an XSS attack, and then write a bot to leave a message under all articles, using <iframe> to redirect users to the article with XSS. In this way, as long as the user clicks on any article, they will be attacked.

However, the defense of other parts of the website itself is well done. Although there is XSS, the Cookie is HttpOnly, so it cannot be stolen, and the password modification is sent by email, so the password cannot be modified. It seems that it is not possible to do really serious things.

Many libraries that filter XSS are safe (although sometimes there are still vulnerabilities found, such as bypassing DOMPurify), but people who use the library may ignore some settings or do extra things, resulting in HTML that is still unsafe.

When dealing with user input, every step should be carefully reviewed to avoid negligence.

It is also recommended to set up CSP headers as a last line of defense against XSS attacks. Although some CSP rules can be bypassed, it is still better than having nothing.

Matters has its own Bug Bounty Program, which offers rewards for finding vulnerabilities that can prove harmful. The XSS vulnerability found in this article is classified as High, with a value of $150 USD. The team believes that open source can benefit technical professionals and make websites more secure, so they hope everyone knows about this program.

Finally, thanks to the Matters team for their quick response and handling, and thanks to the colleagues at Cymetrics.

Timeline:

- May 7, 2021: Vulnerability reported

- May 12, 2021: Received confirmation from the Matters team that they are fixing the vulnerability

- May 12, 2021: Asked for permission to publish the article after the fix, received permission

- May 13, 2021: Fix completed

Comments