Introduction

If you want to store something in the front-end of a website, which means storing it in the browser, there are basically a few options:

- Cookie

- LocalStorage

- SessionStorage

- IndexedDB

- Web SQL

The last two are rarely used, and the last one, Web SQL, was declared deprecated a few years ago. Therefore, when it comes to storing data, most people mention the first three, with the first two being the most commonly used.

After all, when storing data in the front-end, most data is expected to be stored for a period of time, and cookies and localStorage are designed for this purpose. However, sessionStorage is not, as it is only suitable for storing very short-term data.

I don’t know if your understanding of sessionStorage is the same as mine, so let me explain my understanding:

The biggest difference between sessionStorage and localStorage is that the former only exists in one tab. When you close the tab, the data is cleared, so a new tab will have a new sessionStorage, and different tabs will not share the same sessionStorage. However, if it is the same website, the same localStorage can be shared.

But let me ask you this: Is it possible that in a certain scenario, I store something in sessionStorage in tab A, and then a new tab B can also read the sessionStorage in tab A?

You might think it’s impossible, and I used to think so too, as did my colleagues.

But it turns out that it is possible.

I Don’t Understand SessionStorage

As mentioned in the introduction, my understanding of sessionStorage is that it only exists in one tab, and when the tab is closed, it disappears. Also, a new tab will not share the data from the original tab, so it is safe to assume that the sessionStorage in the tab can only be accessed by itself.

However, in a technical sharing session within my company, my supervisor Howard shared a case:

Suppose there is a page A that uses sessionStorage to store some data, and there is a hyperlink to page B within the same origin. Many people would expect that the sessionStorage in page B is empty. But no, it will inherit the sessionStorage from page A.

Yes, it was this case that shattered my naive fantasy about sessionStorage. It turns out that two different tabs can share the same sessionStorage.

Strictly speaking, it is not sharing, but the original sessionStorage will be “copied” to the new tab. If the value is changed on page A, page B cannot get the updated value. Page B only copies the sessionStorage at the moment the link is clicked.

I have prepared a demo for everyone to play with, which is just two simple pages. Here is the URL: sessionStorage demo.

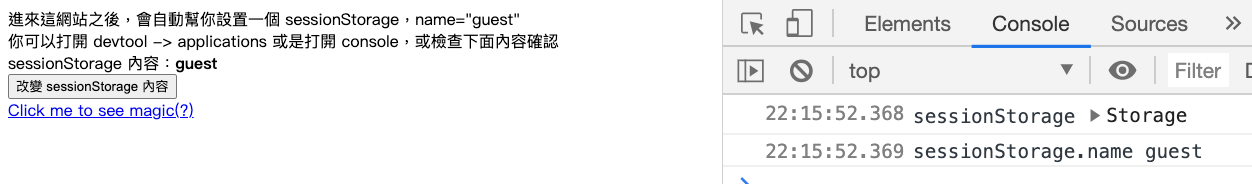

The page looks like this:

The code for this page is very simple. Basically, it sets a sessionStorage with name=guest and displays it on the screen. There is a hyperlink that can be clicked to open a new tab, and a button that randomly updates the value in sessionStorage:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>SessionStorage 範例</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<script>

sessionStorage.setItem('name', 'guest')

</script>

</head>

<body>

<div>

進來這網站之後,會自動幫你設置一個 sessionStorage,name="guest" <br>

你可以打開 devtool -> applications 或是打開 console,或檢查下面內容確認

</div>

<div>

sessionStorage 內容:<b></b>

</div>

<button id="btn">改變 sessionStorage 內容</button><br>

<a href="new_tab.html" target="_blank">Click me to see magic(?)</a>

<script>

document.querySelector('b').innerText = sessionStorage.getItem('name')

console.log('sessionStorage', sessionStorage)

console.log('sessionStorage.name', sessionStorage.name)

btn.addEventListener('click',() => {

sessionStorage.setItem('name', (Math.random()).toString(16))

document.querySelector('b').innerText = sessionStorage.getItem('name')

console.log('updated sessionStorage', sessionStorage)

console.log('updated sessionStorage.name', sessionStorage.name)

})

</script>

</body>

</html>If you click the hyperlink and go to the new page, you will see that the sessionStorage has been copied over:

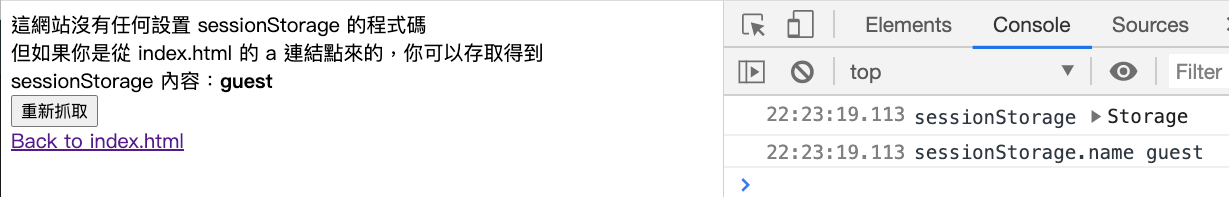

The code for this new page is as follows, and there is no line that sets sessionStorage:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>SessionStorage 範例</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

</head>

<body>

<div>

這網站沒有任何設置 sessionStorage 的程式碼<br>

但如果你是從 index.html 的 a 連結點來的,你可以存取得到

</div>

<div>

sessionStorage 內容:<b></b>

</div>

<button id='btn'>重新抓取</button><br>

<a href="index.html">Back to index.html</a>

<script>

document.querySelector('b').innerText = sessionStorage.getItem('name')

console.log('sessionStorage', sessionStorage)

console.log('sessionStorage.name', sessionStorage.name)

btn.addEventListener('click', () => {

document.querySelector('b').innerText = sessionStorage.getItem('name')

console.log('latest sessionStorage', sessionStorage)

console.log('latest sessionStorage.name', sessionStorage.name)

})

</script>

</body>

</html>Because it is a new tab, you now have two tabs, one is the original index.html, and the other is the new new_tab.html. You can click “Change the content of sessionStorage” in index.html, and you will see the screen update. Then go to new_tab.html and click “Reload”, and you will find that the value has not changed.

This is what I said earlier, it is actually “copying”, not “sharing”. Because if it is sharing, when one place changes, the other place will change with it, but if it is copying, the original content and the copied content will not interfere with each other.

When I heard about this behavior, I was shocked because it was different from what I thought. After the shock, the first thing I thought of was, “Is there a way to avoid this?” My colleagues tried several methods, but none of them worked. I suddenly thought of whether there were some attributes on the hyperlink, such as noopener, noreferrer, or nofollow, but after trying them out, they didn’t work.

Later, I searched for information and finally found a correct solution. Also, I wanted to supplement related knowledge, so I went to see the spec of sessionStorage and found that it was written quite well. Therefore, I would like to share it with you. So, next, we will briefly look at the spec of Web storage. If you only want to know the answer to the problem, you can skip directly to the last paragraph.

Web Storage spec

LocalStorage and sessionStorage are both types of Web Storage. The spec of Web Storage is here: https://html.spec.whatwg.org/multipage/webstorage.html#introduction-16

I think the introduction paragraph at the beginning is written simply and clearly:

This specification introduces two related mechanisms, similar to HTTP session cookies, for storing name-value pairs on the client side

It directly tells you what these two things are doing. They are two mechanisms similar to cookies for storing name-value pairs on the client side.

The first is designed for scenarios where the user is carrying out a single transaction, but could be carrying out multiple transactions in different windows at the same time.

Then, it first talks about the scenario where sessionStorage is needed. This paragraph will be clearer with the following example:

Cookies don’t really handle this case well. For example, a user could be buying plane tickets in two different windows, using the same site. If the site used cookies to keep track of which ticket the user was buying, then as the user clicked from page to page in both windows, the ticket currently being purchased would “leak” from one window to the other, potentially causing the user to buy two tickets for the same flight without really noticing.

The example is roughly like this: Suppose we only have cookies to use, and Xiao Ming is buying plane tickets. Because he wants to buy two “different” tickets, he opens two tabs. However, if the website is not well written and uses cookies to record which ticket he wants to buy, the following situation may occur:

- Xiao Ming clicked on a ticket from Taipei to Japan in tab A, and the website stored this information in a cookie.

- Xiao Ming clicked on a ticket from Taipei to New York in tab B, and the website stored this information in a cookie.

- Since the cookie is shared in tabs A and B, and the key is the same, the cookie now stores the ticket from Taipei to New York.

- Xiao Ming clicked on checkout in tab A and bought a ticket from Taipei to New York.

- Xiao Ming clicked on checkout in tab B and bought another ticket from Taipei to New York.

- So Xiao Ming bought duplicate tickets.

This is the potential problem that may occur when information is stored in cookies. Therefore, sessionStorage is born to solve this problem. It can limit the information to “one session”, which is basically a tab from the perspective of the browser and will not interfere with other tabs.

Further down, it will talk about the usage scenario of localStorage:

The second storage mechanism is designed for storage that spans multiple windows, and lasts beyond the current session. In particular, web applications might wish to store megabytes of user data, such as entire user-authored documents or a user’s mailbox, on the client side for performance reasons.

Again, cookies do not handle this case well, because they are transmitted with every request.

Some websites may want to store a large amount of data in the browser for performance reasons, such as storing users’ emails. This is similar to creating a cache, where the stored data can be retrieved from the cache to speed up loading times.

However, cookies are not suitable for this scenario because they are sent with every request. If you store 1MB of data in a cookie, every request to the website will be at least 1MB in size, and this unnecessary data will cause a lot of traffic.

Therefore, localStorage was created to allow you to store a large amount of data without sending it to the server.

There is also a warning in red below:

The localStorage getter provides access to shared state. This specification does not define the interaction with other browsing contexts in a multiprocess user agent, and authors are encouraged to assume that there is no locking mechanism. A site could, for instance, try to read the value of a key, increment its value, then write it back out, using the new value as a unique identifier for the session; if the site does this twice in two different browser windows at the same time, it might end up using the same “unique” identifier for both sessions, with potentially disastrous effects.

This means that because localStorage can be shared across pages, like other shared resources, you need to be aware of race conditions. For example, if a website reads a key called “id” from localStorage, increments it by 1, and uses it as a unique identifier for the page, two pages doing this at the same time could end up with the same id:

- Page A gets the id, which is 1.

- Page A increments the id by 1.

- At the same time, Page B also gets the id and gets 1.

- Page A writes the id back, and now the id is 2.

- Page B writes the incremented id back, but the id is still 2.

Continuous actions are not guaranteed to be uninterrupted by other processes, which is why it is written that “authors are encouraged to assume that there is no locking mechanism” and to be careful of this situation.

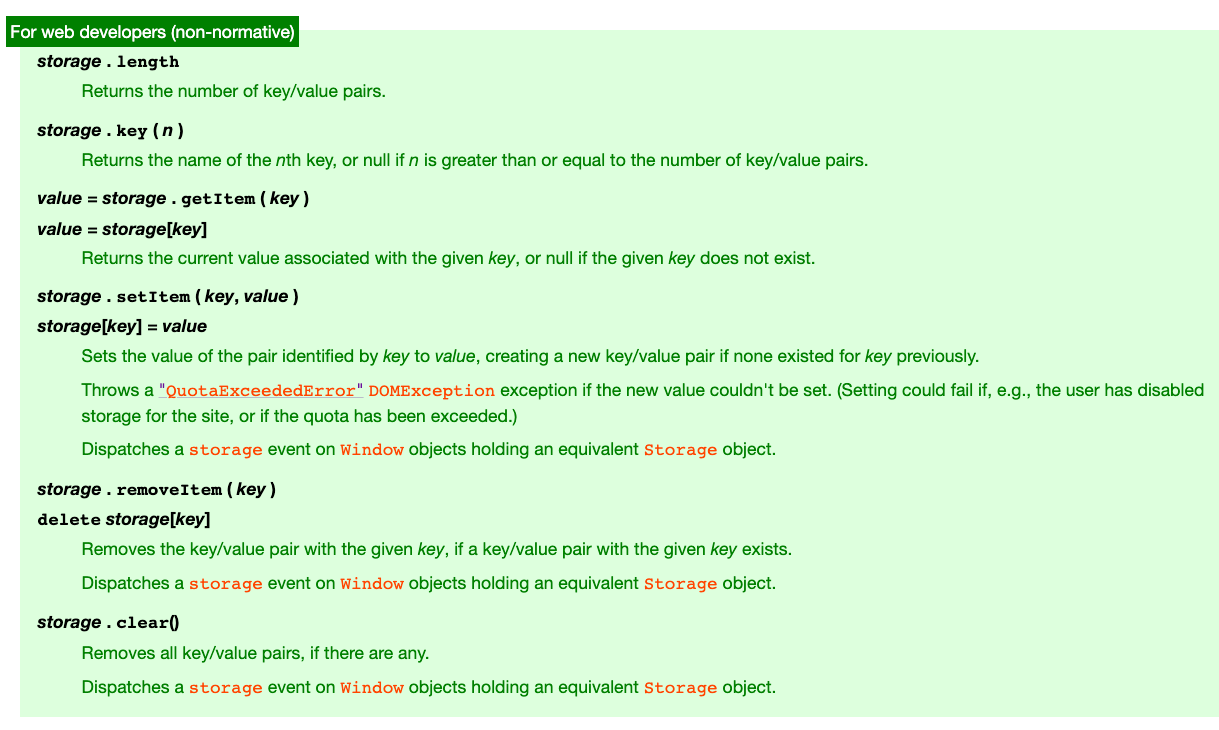

Next, you can see the Web Storage interface:

It is worth noting that although the common usage is storage.setItem or storage.getItem, you can also use storage[key] = value and storage[key] directly. To delete, simply use delete storage[key].

If you cannot write to storage, a QuotaExceededError will be thrown. Chrome’s documentation on chrome.storage provides some related numbers.

There is also a very common phrase:

Dispatches a storage event on Window objects holding an equivalent Storage object.

This is because when the contents of storage change, an event is actually sent out, and you can listen for this event to react accordingly. For example, you can use this trick to detect changes in localStorage in different tabs and respond in real-time. For more information, please see Window: storage event.

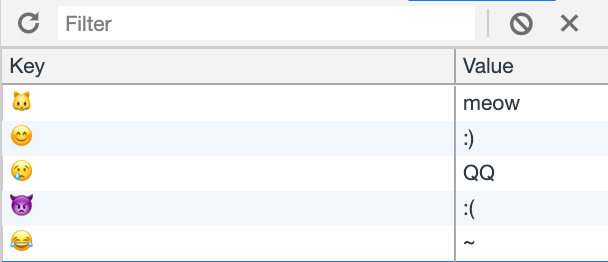

By the way, the key in storage can be an emoji, so if you open this webpage, you can see:

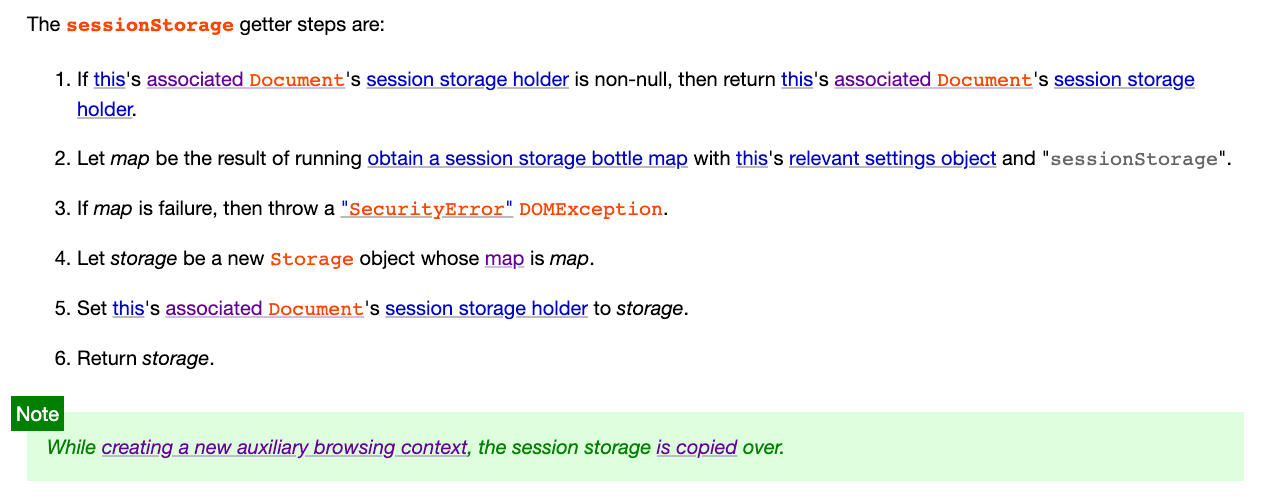

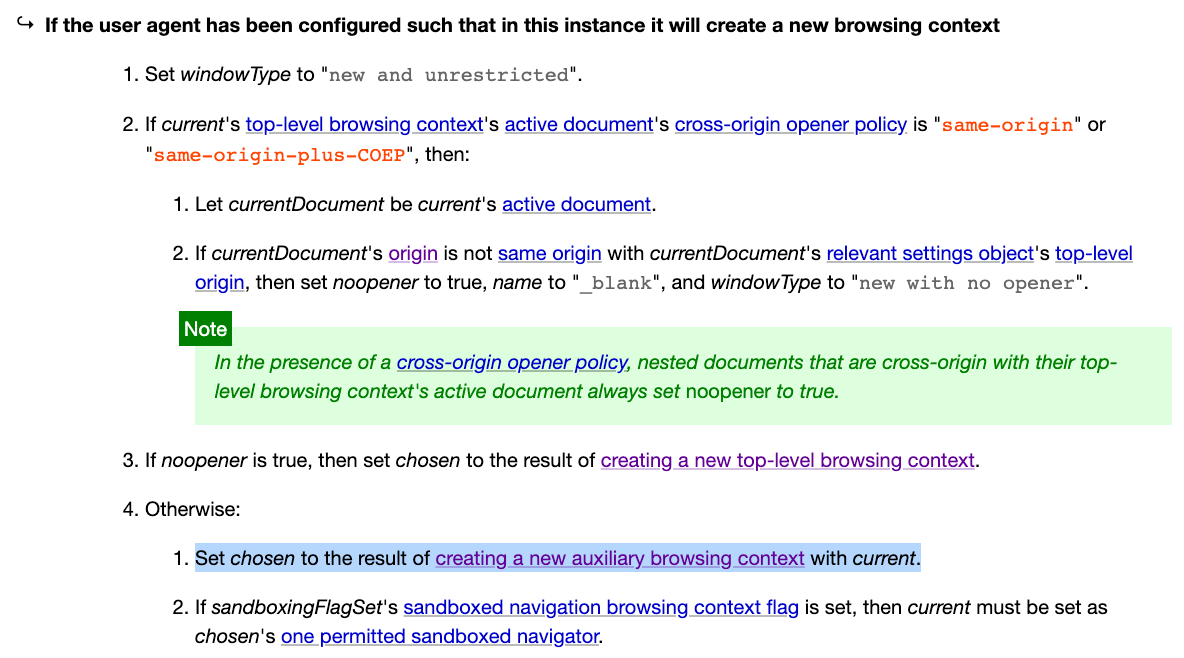

Next, the specs below describe the details of each method. I won’t repeat them here. If you keep scrolling down to the sessionStorage section, you’ll see this paragraph:

Did you catch the key point?

While creating a new auxiliary browsing context, the session storage is copied over.

When creating an auxiliary browsing context, the sessionStorage is copied over. From the example given at the beginning of the article, we can guess that clicking on an “a” tag to open a new tab is probably “creating an auxiliary browsing context”.

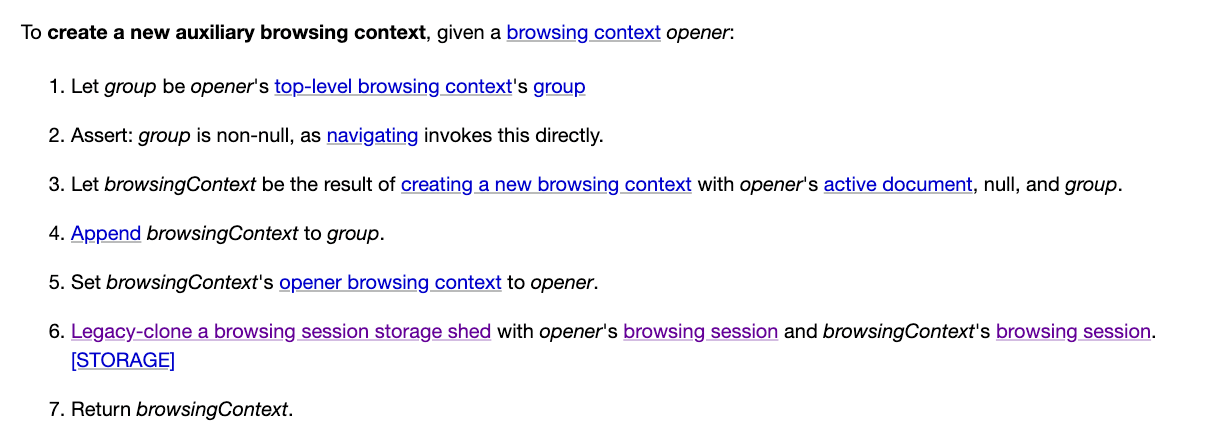

Next, let’s click on it and see what the process of creating an auxiliary browsing context is:

The key point is step six, which mentions that sessionStorage will be copied over.

So now the question has been redefined.

Originally, we were curious about “when will sessionStorage be copied”, and the answer we got was “when creating an auxiliary browsing context”. Therefore, the question we are now curious about is “when will an auxiliary browsing context be created?”

Furthermore, from the results, it appears that the example at the beginning was achieved by linking to an external website through an “a” tag, so we can guess that the answer may be in the spec of the link.

Links spec

The links-related spec is here: https://html.spec.whatwg.org/multipage/links.html

Let’s first look at the definition of a link:

Links are a conceptual construct, created by a, area, form, and link elements, that represent a connection between two resources, one of which is the current Document. There are two kinds of links in HTML:

There are four elements that can create a link: <a>, <area>, <form>, and <link>, with <area> being the one I’ve never heard of before.

Next, the document defines two types of links. The first is: Links to external resources

These are links to resources that are to be used to augment the current document, generally automatically processed by the user agent. All external resource links have a fetch and process the linked resource algorithm which describes how the resource is obtained.

You can think of this as what you use when you use the <link> element, such as CSS, which is a type of external resource. The second type is Hyperlinks:

These are links to other resources that are generally exposed to the user by the user agent so that the user can cause the user agent to navigate to those resources, e.g. to visit them in a browser or download them.

This is the hyperlink we are familiar with, which directs the browser (user agent) to other resources.

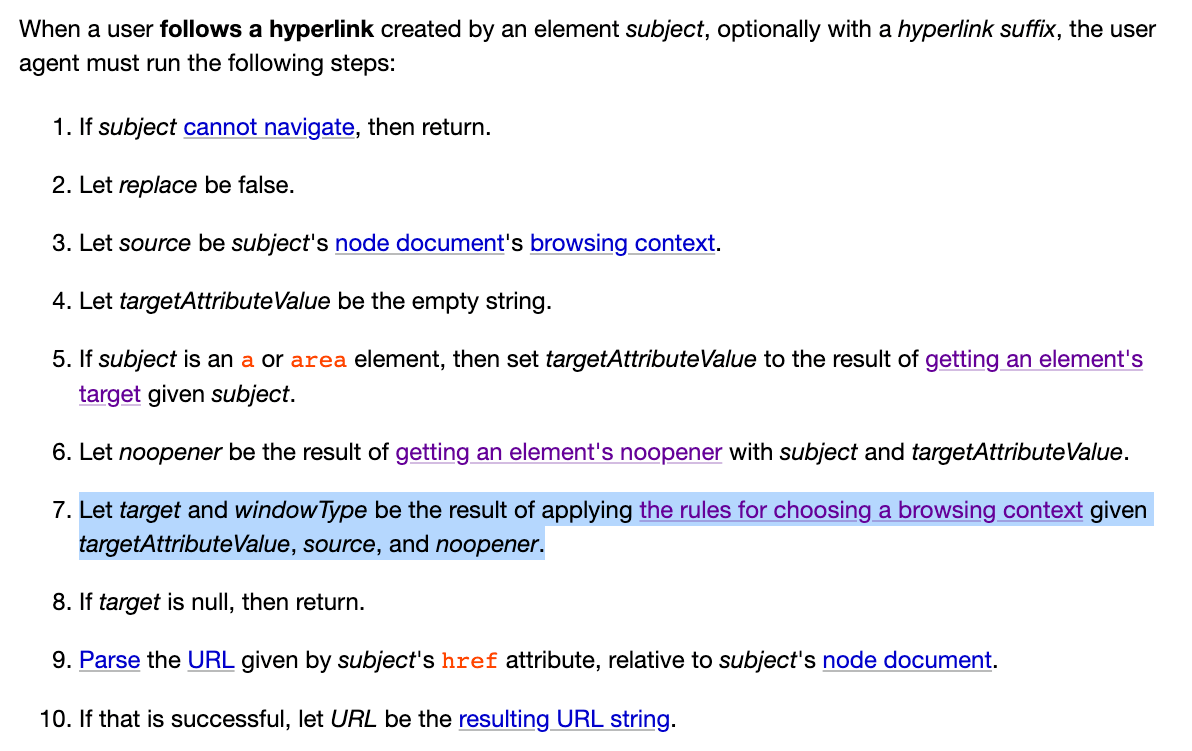

Next, if we keep scrolling down, we can see that 4.6.4 Following hyperlinks mentions what the browser should do when the user clicks on a hyperlink:

The key points are steps six and seven:

- Let noopener be the result of getting an element’s noopener with subject and targetAttributeValue.

- Let target and windowType be the result of applying the rules for choosing a browsing context given targetAttributeValue, source, and noopener.

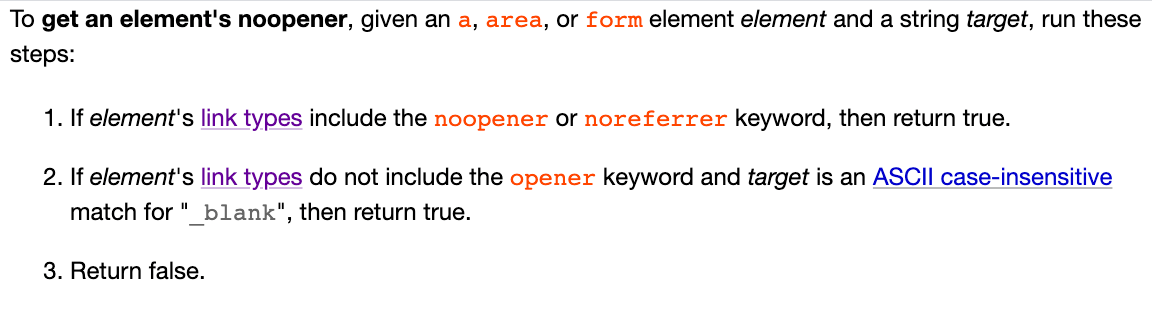

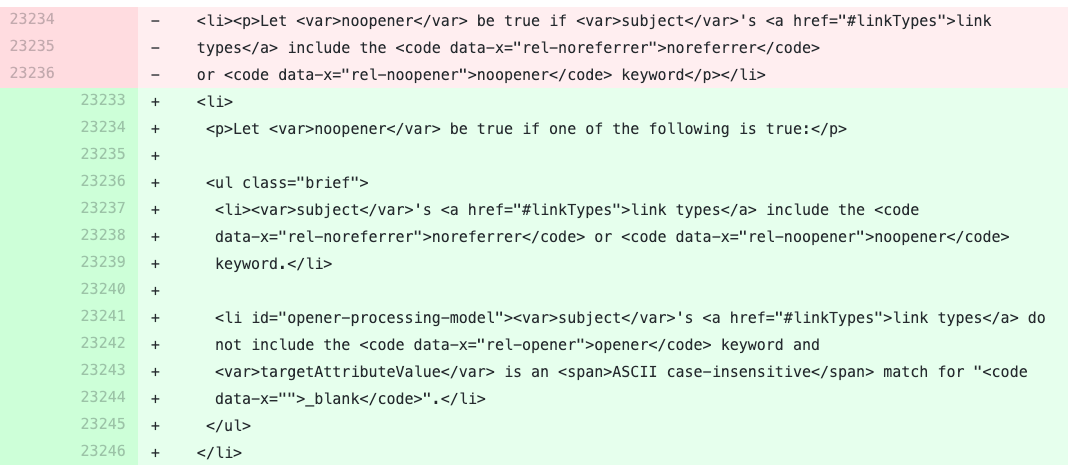

Here, noopener‘s value is determined through the process outlined in the spec:

Our example meets the second condition, where there is no opener attribute and the target is _blank, so noopener will be true.

Next, we look at step seven, which has a link to “the rules for choosing a browsing context” that takes us back to the browsing context spec.

When choosing a browsing context, there are several steps to determine which one to select. None of the cases we are looking for (where the name is _blank) match the previous conditions, so we move directly to step eight:

Otherwise, a new browsing context is being requested, and what happens depends on the user agent’s configuration and abilities — it is determined by the rules given for the first applicable option from the following list:

There are several rules to determine what action to take, and our example falls under this rule:

From the process, we can see that if noopener is true in step three, a new top-level browsing context is created. Otherwise, an auxiliary browsing context is created.

So, if we reach this point and noopener is false, an auxiliary browsing context is created, and the sessionStorage is copied over.

Wait a minute… isn’t our noopener true? Based on our situation, the spec clearly states that it should be true, so a new top-level browsing context should be created, and the sessionStorage should not be copied over.

Did I miss something?

Getting Confused by the Spec on the First Try

I was confident when I started writing this article, but then I came across the situation above: “Huh, why doesn’t the actual behavior match the spec?” I kept thinking that I had missed something, so I checked it several times, and found that it was correct. noopener should indeed be true, so an auxiliary browsing context should not be created, and the sessionStorage should not be copied over.

However, what I observed in Chrome was not like this. So I suddenly thought of a possibility: Chrome did not follow the spec. Here, it is important to note that the spec we are looking at is the latest spec, but browsers usually do not keep up with the latest version, and some things may be breaking changes, so they may be slower.

Therefore, I speculated that the spec had been changed, and Chrome was following the old behavior. With this speculation, I searched for related keywords and found a commit: Make target=_blank imply noopener; support opener.

This is a commit from February 7, 2019, and in the diff, we can see this change:

In the old spec, noopener is only true if the noopener or noreferrer attribute is true, otherwise it is false. Therefore, the behavior observed at the beginning is consistent with the old spec. We opened a new page with a link using the a tag, without setting noopener and noreferrer, so a new auxiliary browsing context was created and sessionStorage was copied over. Now that we have a reasonable and authoritative explanation, we only have a few more questions to address: What are noopener and noreferrer? Why did the spec make this change? The noopener and noreferrer attributes were first seen by the author in May 2016. When using the a tag to link from website A to website B, website B can obtain window.opener, which is equivalent to website A’s window. Therefore, if I execute window.opener.location = ‘phishing_site_url’ on website B, I can redirect website A to another location. The solution is to add the rel=”noopener” attribute. The noreferrer attribute is related to the Referer HTTP request header. If I link from website A to website B, website B’s Referer will be the URL of website A, so it will know where you came from. Adding this attribute tells the browser not to include the Referer header.

To see more details, you can refer to this issue: target=_blank rel=noreferrer implies noopener. Originally, there were concerns that some old browsers might have problems, so no changes were made. Later, someone provided a lot of browser testing data, and after confirming that there were no problems, changes were made.

Let’s bring the topic back to the opener issue. When this issue was first revealed, I remember it received a lot of attention, and there were a lot of related discussions on the spec’s repo. In fact, many people were surprised that the default behavior was like this.

You can refer to this thread for related discussions: Windows opened via a target=_blank should not have an opener by default, and this PR: Make target=_blank imply noopener; support opener.

Anyway, later on, Safari and Firefox made changes to this point. When using target=_blank, the default opener will be noopener.

What about Chrome? Sorry, not yet. You can refer to: Issue 898942: Anchor target=_blank should imply rel=noopener.

Back to sessionStorage

After going around in circles and looking at a lot of specs and bug trackers, we finally come back to the original topic: sessionStorage.

The spec says that if an auxiliary browsing context is created, sessionStorage will be copied over. And if we add rel="noopener", this behavior will not occur.

So this is the correct answer to the initial problem: “Add rel="noopener"“.

But as I mentioned at the beginning, I tried all of these and none of them worked. Why is that? This is because Chrome does not yet support this behavior: Issue 771959: Do not copy sessionStorage when a window is created with noopener. And although Safari says that target=_blank implies rel="noopener", it also does not support noopener not copying sessionStorage.

The only browser that conforms to the latest standard is Firefox. If you add rel="noopener", sessionStorage will not be copied over.

Since these are behaviors that have not yet been corrected by browsers, we are powerless in development. For now, in Chrome and Safari, opening a new tab in the same origin using <a target="_blank"> will copy sessionStorage.

One last reminder: the behavior of “clicking a link” and “right-click -> open in new tab” is different. The former will copy sessionStorage, but the latter will not. This is because the browser (at least Chrome and Safari) thinks that “right-click -> open in new tab” is like opening a new tab and copying and pasting the URL, rather than directly linking from the existing tab, so it will not copy sessionStorage.

Once again, here is the demo from the beginning. Try it yourself: https://aszx87410.github.io/demo/session_storage/index.html

For related discussions, please refer to: Issue 165452: sessionStorage variables not being copied to new tab.

Conclusion

Starting from sessionStorage and extending outward, we have explored many new things, and even linked to the article on the security of noopener that I saw a few years ago, as well as the eslint warning I encountered when writing code before. If you want to continue linking, you can even link to Chrome’s recent changes to Referer. So even though it’s just a seemingly small piece of knowledge, there is a whole big knowledge map behind it.

After discovering that the spec and implementation were different, I instantly realized the feeling of “trust the book rather than having no book”. I always thought that the spec was the only authority, but I ignored the fact that the spec would constantly change and update, but the implementation might not keep up. Another point is that the implementation of the browser sometimes does not follow the spec due to some considerations, which is also something to be particularly aware of in the future.

After going through such a journey, I have a deeper understanding of sessionStorage. If there is a chance in the future, it is better to flip through all the HTML specs, and there should be more interesting things to see.

References:

- HTML spec

- About rel=noopener, what problems does it solve?

- target=_blank rel=noreferrer implies noopener

- Windows opened via a target=_blank should not have an opener by default

- Issue 898942: Anchor target=_blank should imply rel=noopener

- Issue 771959: Do not copy sessionStorage when a window is created with noopener

- Issue 165452: sessionStorage variables not being copied to new tab

Comments