Introduction

This is a series of three articles, which I call the “Session and Cookie Trilogy”. The goal of this series is to discuss this classic topic from shallow to deep, from understanding concepts to understanding implementation methods. This is the second article in the series, and the complete links to the three articles are as follows:

- Plain Talk on Session and Cookie: Starting with Running a Grocery Store

- A Brief Discussion on Session and Cookie: Reading RFC Together

- In-depth Session and Cookie: Implementation in Express, PHP, and Rails

In the previous article, we mentioned the meaning of Session:

What is a Session? It is a mechanism that makes Request stateful. In the example of Xiao Ming, Session is a mechanism that allows guests to be related to each other. In the story, we used notes and information in the phone to compare, and there are many ways to achieve Session.

In fact, when writing this series, “What is the clearest definition of Session” troubled me for a while, and I still can’t be completely sure what is right. In my mind, there are two explanations that are quite reasonable. The first explanation is what we talked about in the previous article. Session is a mechanism that makes Request stateful, and the second explanation of Session (also a more close to the original English explanation) is “a period of time with state” or “context”, so things in Session can be viewed together.

There is a saying that the original meaning of Session is indeed the second one, but in the Web field, Session has become a “mechanism”, so both meanings are acceptable. But I actually tend to think that the second one is the only correct explanation method, and the second one is correct from beginning to end, while the first one is a misunderstanding.

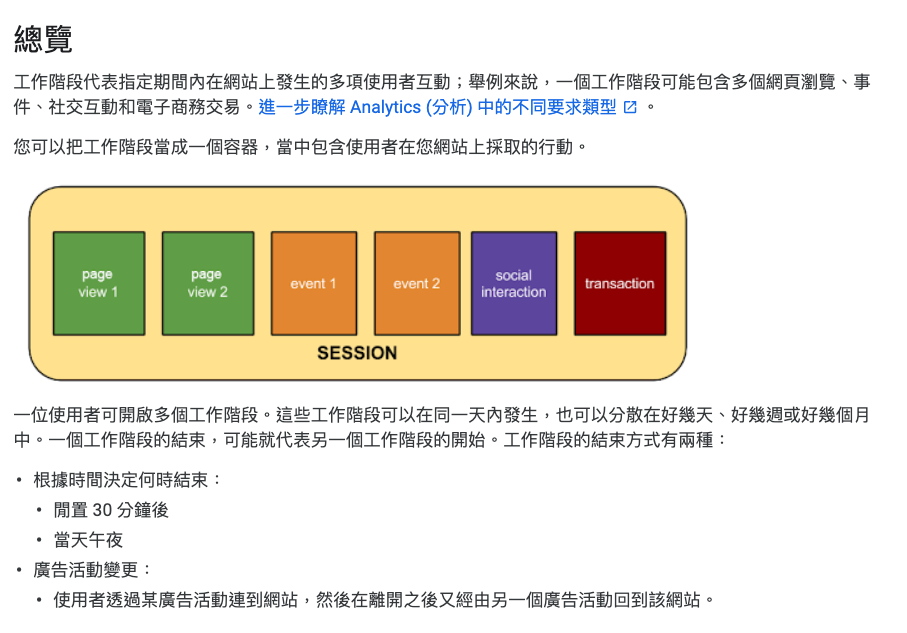

For example, if you have used Google Analytics, there is a term called “session”, and the English name is Session. Google’s interpretation of Session is as follows:

(Source: Analytics Definition of Website Session)

It defines Session as “multiple user interactions that occur on the website during a specified period of time” and says that Session can be used as a container. Although Google Analytics’ Session is different from the Session used in Web technology, I think they can refer to each other to some extent. And the definition of this Session is similar to what I said before, “a period of time with state” or “context”.

So why did I not mention it in the previous article and define Session as a “misunderstanding” in my eyes, even though I tend to this definition?

The first reason is that both explanations may be acceptable, so both may be correct. The second reason is that I think the precise definition of Session is very difficult to explain because the concept is too abstract. I think that if this explanation is mentioned, it will only make your understanding of Session more confusing, so it was not mentioned in the previous article. The third reason is that I think it is also possible to explain it as a mechanism, and it is easier to understand. Even if it is really wrong, the impact is not that great.

In short, I think that for people who have no foundation at all, understanding Session as a mechanism is enough. But for people like me who want to dig deeper, what I want to know is the most correct understanding, and it must be based on evidence.

What is considered evidence? Reading the RFC documents that discussed Cookie and Session at that time should be convincing enough, right? RFC documents have to go through a series of discussions and reviews before they can be born. I can’t think of any explanation that is more convincing than RFC.

In this article, we will read three RFCs:

Why read three? Because these three are all documents related to Cookie. 2109 is the earliest one. Later, some problems occurred, so it was replaced by the new 2965. After ten years, 6265 appeared, which is the current standard.

I believe that starting to read something from the earliest possible time can save time and effort, because there will be less content and it will be easier to understand, and it will also be easier to find information. For example, if you want to read the React source code, I would recommend starting from version 0.xx, and for reading ECMAScript, you can start from ES3, and you can also learn about the evolution process.

That’s the background, and the goal of this article is to read the RFC and see how it describes Cookies and Sessions. I will translate some of the original text, but translation is a profession, and my translation may be poor and certainly contains errors. Please still refer to the original text, and consider my translation as a supplement. If there are any serious errors, please let me know, I would be very grateful.

RFC 2109

RFC 2109 was published in February 1997, a time when there was no Ajax and Netscape still dominated the browser market.

The title of this document is “HTTP State Management Mechanism”.

Let’s start with the abstract:

This document specifies a way to create a stateful session with HTTP requests and responses. It describes two new headers, Cookie and Set-Cookie, which carry state information between participating origin servers and user agents. The method described here differs from Netscape’s Cookie proposal, but it can interoperate with HTTP/1.0 user agents that use Netscape’s method. (See the HISTORICAL section.)

This document describes a way to create stateful sessions with HTTP requests and responses. Currently, HTTP servers respond to each client request without relating that request to previous or subsequent requests; the technique allows clients and servers that wish to exchange state information to place HTTP requests and responses within a larger context, which we term a “session”.

The context might be used to create, for example, a “shopping cart”, in which user selections can be aggregated before purchase, or a magazine browsing system, in which a user’s previous reading affects which offerings are presented.

The abstract is very clear. In short, it introduces the use of two headers, Cookie and Set-Cookie, to establish a session. Netscape is mentioned because Cookies were originally implemented by Netscape, but unfortunately, I couldn’t find any links to see what Netscape’s Cookie specifications looked like.

The second part, TERMINOLOGY, defines the usage of some technical terms, which can be skimmed over. The focus is on the third part, STATE AND SESSIONS:

This document describes a way to create stateful sessions with HTTP requests and responses. Currently, HTTP servers respond to each client request without relating that request to previous or subsequent requests; the technique allows clients and servers that wish to exchange state information to place HTTP requests and responses within a larger context, which we term a “session”.

This context might be used to create, for example, a “shopping cart”, in which user selections can be aggregated before purchase, or a magazine browsing system, in which a user’s previous reading affects which offerings are presented.

This section describes how to use HTTP requests and responses to create a stateful session. Currently, HTTP servers respond to each client request independently, without relating it to previous or subsequent requests. This method allows servers and clients that want to exchange state information to place HTTP requests and responses in a larger context, which is called a “session”. This context can be used to create a shopping cart, for example, where user selections can be aggregated before purchase, or a magazine browsing system, where a user’s previous reading affects which offerings are presented.

Here, the definition of Session is just as I mentioned earlier, Session is a “period with state”, or “context”, which means that the Request and Response in this context can be viewed together, and thus they have a state.

There are, of course, many different potential contexts and thus many different potential types of session. The designers’ paradigm for sessions created by the exchange of cookies has these key attributes:

- Each session has a beginning and an end.

- Each session is relatively short-lived.

- Either the user agent or the origin server may terminate a session.

- The session is implicit in the exchange of state information.

There are many different types of sessions, and sessions created by the exchange of cookies have several key points:

- Each session has a beginning and an end.

- Each session is relatively short-lived.

- Either the user agent or the origin server may terminate a session.

- The session is implicit in the exchange of state information.

This section just briefly introduces the characteristics of Session. If we understand Session as a “mechanism”, how do we explain the paragraph above? “Each Session mechanism is relatively short-lived”? It sounds a bit strange, so this is why I said it’s a bit strange to interpret Session as a mechanism.

Next, many parts of Chapter 4 are about the specifications of those Headers. We skip them and only select a few paragraphs that I think are more important:

4.2.1 General

The origin server initiates a session, if it so desires. (…) >

To initiate a session, the origin server returns an extra response header to the client, Set-Cookie. (The details follow later.)A user agent returns a Cookie request header (see below) to the origin server if it chooses to continue a session.

If the Server desires, it can initiate a session, and the way to initiate it is to return a Set-Cookie Header. If the browser decides to continue this session, it can return the Cookie Header.

Simply put, the server sends the state in the Set-Cookie Header to the browser, and the browser brings the Cookie in the subsequent Request, so a Session is established because the subsequent Request has a state.

Next, let’s take a look at the EXAMPLES section in Chapter 5. Let’s take one of the examples. This example is relatively simple, so I’ll just translate it into Chinese. If you want to see the original text, you can go here: 5.1 Example 1.

Step 1: Browser -> Server

POST /acme/login HTTP/1.1

[form data]The user logs in through the form.

Step 2: Server -> Browser

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Set-Cookie: Customer="WILE_E_COYOTE"; Version="1"; Path="/acme"Login successful, the server sends a Set-Cookie Header and sets the information, storing the user’s identity.

Step 3: Browser -> Server

POST /acme/pickitem HTTP/1.1

Cookie: $Version="1"; Customer="WILE_E_COYOTE"; $Path="/acme"

[form data]The user adds an item to the shopping cart.

Step 4: Server -> Browser

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Set-Cookie: Part_Number="Rocket_Launcher_0001"; Version="1"; Path="/acme"Step 4: Server sets a cookie to store the items just added to the shopping cart.

Step 5: Browser -> Server

POST /acme/shipping HTTP/1.1

Cookie: $Version="1";

Customer="WILE_E_COYOTE"; $Path="/acme";

Part_Number="Rocket_Launcher_0001"; $Path="/acme"

[form data]The user selects the shipping method using a form.

Step 6: Server -> Browser

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Set-Cookie: Shipping="FedEx"; Version="1"; Path="/acme"A new cookie is set to store the shipping method.

Step 7: Browser -> Server

POST /acme/process HTTP/1.1

Cookie: $Version="1";

Customer="WILE_E_COYOTE"; $Path="/acme";

Part_Number="Rocket_Launcher_0001"; $Path="/acme"

Shipping="FedEx"; $Path="/acme"

[form data]The user selects checkout.

Step 8: Server -> Browser

HTTP/1.1 200 OKThe transaction is completed based on the user data, purchased items, and shipping method carried by the cookie header sent by the browser.

The above example roughly explains how cookies work. The server sends the Set-Cookie header to set the information, and the browser sends the Cookie header to carry the previously stored information, creating a state and starting a session.

Next, let’s look at the IMPLEMENTATION CONSIDERATIONS section, which discusses some implementation considerations. Here’s an excerpt:

6.1 Set-Cookie Content

The session information can obviously be clear or encoded text that describes state. However, if it grows too large, it can become unwieldy. Therefore, an implementor might choose for the session information to be a key to a server-side resource. Of course, using a database creates some problems that this state management specification was meant to avoid, namely:

- keeping real state on the server side;

- how and when to garbage-collect the database entry, in case the user agent terminates the session by, for example, exiting.

The session information stored in the cookie can be clear or encoded text that describes the state. However, if the stored information becomes too large, it can become unwieldy. Therefore, you can choose to store only a key that corresponds to a server resource in the session information. However, this approach creates some problems that this state management specification was meant to avoid, namely:

- keeping real state on the server side;

- how and when to garbage-collect the database entry, in case the user agent terminates the session by, for example, exiting.

In fact, these two different methods are the Cookie-based session and SessionID mentioned in the previous article. The former’s disadvantage is that storing too much information can become unwieldy, while the latter requires storing the state on the server.

Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages, but the SessionID method is more commonly used, which is what the original article refers to as “session information to be a key to a server-side resource.”

Other parts of the article discuss security or privacy-related issues, which are somewhat different from the topic we are discussing here, so I will not go into detail.

Let’s summarize what we have learned so far.

First, cookies were created to establish sessions because before that, sessions could only be established through the methods mentioned in my previous article, such as using the URL or putting a hidden field in a form. Cookies were created to simplify these actions.

The actual method is for the server to return the Set-Cookie header, and the user agent stores this information and adds a Cookie header to subsequent requests. This is what we referred to as a “note” in the previous article, which is carried every time and creates a state between requests.

You can put any state in the cookie, but if there is too much information, you can consider moving this state to the server and only storing an ID that corresponds to it in the cookie. This is what we previously referred to as Session ID and Session Data.

RFC 2965 was born in 2000, but its content is not far from RFC 2109, with about 80% of the content being the same.

Why?

Shortly after RFC 2109 was released, they discovered that IE3 and Netscape Navigator3 implemented the “new” cookie standard (the old one being Netscape’s original specification) differently. For example, in the following section:

Set-cookie: xx="1=2\&3-4";

Comment="blah";

Version=1; Max-Age=15552000; Path=/;

Expires=Sun, 27 Apr 1997 01:16:23 GMTIn IE, the cookie is set to Cookie: Max-Age=15552000, while in Netscape Navigator it is what we expect: Cookie: xx="1=2\&3-4". The same header produces different results, so they had to find a way to correct this behavior.

Finally, RFC 2965 was introduced, which introduced two new headers: Cookie2 and Set-Cookie2, with the rest being similar to RFC 2109.

Therefore, we can skip 2965 and go straight to the latest RFC 6265.

RFC 6265

RFC 6265 is a document that appeared in 2011, 11 years after the previous one.

This document can be said to have updated the cookie rules again, with significant changes. The Introduction explains:

Prior to this document, there were at least three descriptions of cookies: the so-called “Netscape cookie specification” [Netscape], RFC 2109 [RFC2109], and RFC 2965 [RFC2965]. However, none of these documents describe how the Cookie and Set-Cookie headers are actually used on the Internet (see [Kri2001] for historical context).

Before this document, there were at least three different cookie specifications: the first was Netscape’s specification, followed by RFC 2109 and 2965. However, none of these documents really describe how we use cookies and Set-Cookie today.

Some of the attributes we use today did not exist in RFC 2965, such as HttpOnly. This specification defines many things more clearly, and interested readers can read it themselves.

Next, let’s look at some interesting places. The first is 3.1 Examples, which mentions the use of SessionID directly:

3.1. Examples

Using the Set-Cookie header, a server can send the user agent a short string in an HTTP response that the user agent will return in future HTTP requests that are within the scope of the cookie. For example, the server can send the user agent a “session identifier” named SID with the value 31d4d96e407aad42. The user agent then returns the session identifier in subsequent requests.

Using the Set-Cookie header, a server can send the user agent a short string in an HTTP response that the user agent will return in future HTTP requests that are within the scope of the cookie. For example, the server can send the user agent a “session identifier” named SID with the value 31d4d96e407aad42. The user agent then returns the session identifier in subsequent requests.

There is also a more complete example below, but it’s a bit long so I won’t translate it. I actually recommend that everyone read the entire document because it defines the cookie specifications we use today (basically, although there are still some differences), and you can get the most accurate information from the specifications.

For example:

4.1.2.5. The Secure Attribute

The Secure attribute limits the scope of the cookie to “secure” channels (where “secure” is defined by the user agent). When a cookie has the Secure attribute, the user agent will include the cookie in an HTTP request only if the request is transmitted over a secure channel (typically HTTP over Transport Layer Security (TLS)[RFC2818]).

The Secure attribute limits the scope of the cookie to “secure” channels (where “secure” is defined by the user agent). When a cookie has the Secure attribute, the user agent will include the cookie in an HTTP request only if the request is transmitted over a secure channel (typically HTTP over Transport Layer Security (TLS)[RFC2818]).

Here’s the translated text:

Here we can see the difference between specifications and implementations. The specification only states that “what is secure is defined by the user agent itself”, and does not enforce the rule that “transmission can only occur when using HTTPS”. Therefore, what we generally understand as “Secure means that it can only be transmitted through HTTPS” actually refers to the implementation of mainstream browsers, not the specification of RFC.

So, to fully answer the question “what does setting the Secure attribute mean”, you can answer like this:

It means that this cookie can only be transmitted through a secure channel. As for what is secure, RFC states that it is defined by the browser itself. Based on the current mainstream implementation, it means that it can only be transmitted through HTTPS.

Next, let’s take a look at something that is closely related to us:

- Privacy Considerations

Cookies are often criticized for letting servers track users. For example, a number of “web analytics” companies use cookies to recognize when a user returns to a web site or visits another web site. Although cookies are not the only mechanism servers can use to track users across HTTP requests, cookies facilitate tracking because they are persistent across user agent sessions and can be shared between hosts.

Cookies are often criticized for letting servers track users. For example, a number of “web analytics” companies use cookies to recognize when a user returns to a web site or visits another web site. Although cookies are not the only mechanism servers can use to track users across HTTP requests, cookies facilitate tracking because they are persistent across user agent sessions and can be shared between hosts.

7.1. Third-Party Cookies

Particularly worrisome are so-called “third-party” cookies. In rendering an HTML document, a user agent often requests resources from other servers (such as advertising networks). These third-party servers can use cookies to track the user even if the user never visits the server directly. For example, if a user visits a site that contains content from a third party and then later visits another site that contains content from the same third party, the third party can track the user between the two sites.

Third-party cookie blocking policies are often ineffective at achieving their privacy goals if servers attempt to work around their restrictions to track users. In particular, two collaborating servers can often track users without using cookies at all by injecting identifying information into dynamic URLs.

Cookies are often criticized for allowing servers to track users. For example, many “web analytics” companies use cookies to recognize when a user returns to a website or visits another website. Although cookies are not the only mechanism servers can use to track users across HTTP requests, cookies facilitate tracking because they are persistent across user agent sessions and can be shared between hosts.

Particularly worrisome are so-called “third-party” cookies. In rendering an HTML document, a user agent often requests resources from other servers (such as advertising networks). These third-party servers can use cookies to track the user even if the user never visits the server directly. For example, if a user visits a site that contains content from a third party and then later visits another site that contains content from the same third party, the third party can track the user between the two sites.

Third-party cookie blocking policies are often ineffective at achieving their privacy goals if servers attempt to work around their restrictions to track users. In particular, two collaborating servers can often track users without using cookies at all by injecting identifying information into dynamic URLs.

In fact, the issue of third-party cookies was discussed in RFC 2109, which was then called Unverifiable Transactions. When I saw it, I was surprised that the problem of third-party cookies had already been mentioned in 1997 when cookies had just emerged.

After all, this issue has only been widely discussed recently, and it was only in recent years that Safari and Firefox began blocking third-party cookies by default. Even Facebook’s solution, dynamic URLs, had already appeared in RFC 6265 (I hate that fbcid string…).

Finally, let’s take a look at some security-related things, all of which are in section 8.Security Considerations:

8.4. Session Identifiers

Instead of storing session information directly in a cookie (where it might be exposed to or replayed by an attacker), servers commonly store a nonce (or “session identifier”) in a cookie. When the server receives an HTTP request with a nonce, the server can look up state information associated with the cookie using the nonce as a key.

Instead of storing session information directly in a cookie, servers usually only store a session ID in the cookie. When the server receives this session ID, it can find the corresponding data.

Using session identifier cookies limits the damage an attacker can cause if the attacker learns the contents of a cookie because the nonce is useful only for interacting with the server (unlike non- nonce cookie content, which might itself be sensitive). Furthermore, using a single nonce prevents an attacker from “splicing” together cookie content from two interactions with the server, which could cause the server to behave unexpectedly.

Compared to directly storing sensitive information in cookies, only storing session IDs can limit the damage that attackers can cause, because even if attackers know that there is a session ID stored inside, it is useless. (I don’t quite understand the “splicing” part.)

Using session identifiers is not without risk. For example, the server SHOULD take care to avoid “session fixation” vulnerabilities. A session fixation attack proceeds in three steps. First, the attacker transplants a session identifier from his or her user agent to the victim’s user agent. Second, the victim uses that session identifier to interact with the server, possibly imbuing the session identifier with the user’s credentials or confidential information. Third, the attacker uses the session identifier to interact with server directly, possibly obtaining the user’s authority or confidential information.

Using session IDs is not completely risk-free. For example, the server should avoid session fixation attacks. This type of attack has three steps: first, the attacker generates a session ID and passes it to the victim; second, the victim logs in using this session ID; after the victim logs in, the attacker can use the same session ID to obtain the victim’s data.

The original article did not provide a clear explanation of session fixation. Interested readers can refer to HTTP Session Attacks and Protection for a clearer explanation.

In simple terms, session fixation is when the victim logs in using the session ID specified by the attacker. As a result, the session ID on the server side is bound to the victim’s account. Then, using the same session ID, the attacker can log in and use the website as the victim.

Now let’s look at another security issue:

8.6. Weak Integrity

Cookies do not provide integrity guarantees for sibling domains (and their subdomains). For example, consider foo.example.com and bar.example.com. The foo.example.com server can set a cookie with a Domain attribute of “example.com” (possibly overwriting an existing “example.com” cookie set by bar.example.com), and the user agent will include that cookie in HTTP requests to bar.example.com. In the worst case, bar.example.com will be unable to distinguish this cookie from a cookie it set itself. The foo.example.com server might be able to leverage this ability to mount an attack against bar.example.com.

Cookies do not provide integrity guarantees for subdomains. For example, foo.example.com can set a cookie for example.com, which may overwrite the cookie set by bar.example.com for example.com. In the worst case, when bar.example.com receives this cookie, it cannot distinguish whether it was set by itself or by someone else. Foo.example.com can use this feature to attack bar.example.com.

An active network attacker can also inject cookies into the Cookie header sent to https://example.com/ by impersonating a response from http://example.com/ and injecting a Set-Cookie header. The HTTPS server at example.com will be unable to distinguish these cookies from cookies that it set itself in an HTTPS response. An active network attacker might be able to leverage this ability to mount an attack against example.com even if example.com uses HTTPS exclusively.

Attackers can also use http://example.com/ to overwrite cookies from https://example.com/ (the former is http and the latter is https), and the server cannot distinguish whether the cookie was set by http or https. Attackers can also use this feature to launch attacks.

The above paragraph is also mentioned in 4.1.2.5 The Secure Attribute:

Although seemingly useful for protecting cookies from active network attackers, the Secure attribute protects only the cookie’s confidentiality. An active network attacker can overwrite Secure cookies from an insecure channel, disrupting their integrity.

The gist of it is that the Secure attribute cannot guarantee the integrity of cookies. Attackers can overwrite HTTPS cookies with HTTP. When I read this, I was shocked because it was the same issue I wrote about before: The Most Difficult Cookie Problem I’ve Encountered. Now I finally understand why Safari and Firefox didn’t block this behavior, because the specification doesn’t require it.

As for Chrome, its implementation refers to several different RFCs. In the CookieMonster responsible for managing cookies, it is written that:

CookieMonster requirements are, in theory, specified by various RFCs. RFC 6265 is currently controlling, and supersedes RFC 2965.

However, most browsers do not actually follow those RFCs, and Chromium has compatibility with existing browsers as a higher priority than RFC compliance.

An RFC that more closely describes how browsers normally handles cookies is being considered by the RFC; it is available at http://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-ietf-httpstate-cookie. The various RFCs should be examined to understand basic cookie behavior; this document will only describe variations from the RFCs.

In CookieMonster.cc, it is also written that:

If the cookie is being set from an insecure scheme, then if a cookie already exists with the same name and it is Secure, then the cookie should not be updated if they domain-match and ignoring the path attribute.

See: https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-ietf-httpbis-cookie-alone

The document mentioned in the article is still in draft stage, titled “Deprecate modification of ‘secure’ cookies from non-secure origins,” and was initiated by Google employees. The Introduction is very clear:

Section 8.5 and Section 8.6 of [RFC6265] spell out some of the drawbacks of cookies’ implementation: due to historical accident, non-secure origins can set cookies which will be delivered to secure origins in a manner indistinguishable from cookies set by that origin itself. This enables a number of attacks, which have been recently spelled out in some detail in [COOKIE-INTEGRITY].

We can mitigate the risk of these attacks by making it more difficult for non-secure origins to influence the state of secure origins. Accordingly, this document recommends the deprecation and removal of non-secure origins’ ability to write cookies with a ‘secure’ flag, and their ability to overwrite cookies whose ‘secure’ flag is set.

The gist of this article is similar to what we saw in Sections 8.5 and 8.6 of RFC 6265. Due to some historical reasons, secure cookies can be overridden by non-secure sources. This document aims to prevent this behavior.

Having read all the documents related to sessions and cookies, let’s summarize.

Summary

Going back to the initial question: what is a session?

From the various session-related terms mentioned in the RFC, I believe that a session is one of its original meanings in English, representing “a period with a state” or “context.” Therefore, to open or create a session, it is necessary to have a mechanism to establish and maintain the state.

This is also why the RFC title for cookies is “HTTP State Management Mechanism.” Before cookies appeared, sessions could still be established by putting state information in the URL or hiding it in form forms. But after cookies appeared, it became easier to create sessions, just by using the Set-Cookie and Cookie headers.

After creating a session, the stored state is called session information. If you choose to store this information in a cookie, it is called a cookie-based session. Another method is to store only a SessionID in the cookie, and store other session information on the server, linking the two through this ID.

In addition to sessions, we also see some interesting things in the RFC, such as privacy concerns about third-party cookies and security issues related to cookies. These can also deepen your understanding of cookies.

Before ending, I sincerely recommend an article: HTTP Cookies: Standards, Privacy, and Politics. You can download the PDF on the right side of the webpage to read it. The author of this article is also the author of RFC 2109 and 2965. The article clearly explains the history of cookies and what happened at the time. I strongly recommend that everyone take some time to read this article, which can deepen your understanding of the early history of cookies and sessions.

Finally, don’t forget that this is the second article in the series. In the next article, we will look at how mainstream frameworks handle sessions.

The complete links for the three articles are as follows:

Comments